CONTINUING THE REVOLUTION: The Political Thought of Mao by John Bryan Starr '61 Princeton, 1979. 366 pp. $20, $5.95 paper

The recent trail in Beijing of the Gang of Four Mao Zedong's widow, Jiang Qing, and three associates has focused renewed attention on the Cultural Revolution, a period of upheaval from 1966 to 1976 that is now widely described in official Chinese circles as "a catastrophe." Jiang Qing was tried as a reactionary, an ultra-rightist who had plotted the overthrow of the state, but in fact her crimes were those of an ultra-revolutionary. In her spirited defense, Madame Mao disrupted the trial by shouting, "Making revolution is always correct," and she made it clear, despite the attempts of a highly biased court to silence her and avoid the issue of ultimate responsibility, that all she had done had been sanctified by the chairman's blessing: "I was Chairman Mao's dog. Whomever he told me to bite, I bit."

The trial of the Gang of Four encapsulates a struggle that has characterized the People's Republic of China since its founding: a struggle between such administratively inclined moderates as Zhou Enlai and Deng Xiaoping, who wanted to consolidate the very considerable gains of the revolution, and the everrevolutionary Mao, who could proclaim, "There is great disorder under Heaven; the situation is very good." Mao believed ardently that the revolution had to be continued perpetually and that disorder was a creative means toward that end.

Nothing in the Marxist-Leninist-Stalinist tradition prepares us for that view. Hitherto, successful socialist revolutions had proclaimed forthwith that class conflict had been eliminated from society and that the need for revolutionary struggle was therefore at an end.

In an excellent book that combines broad theoretical insight with meticulous scholarship in the whole corpus of Mao's published writings and speeches, John Bryan Starr examines the theme of the continuing revolution that pervaded Mao Zedong's thought and which Mao himself regarded as the culmination of his theoretical contribution to Marxism-Leninism. The author points out that a concept of conflict is übiquitous in political philosophy, but that it has been regarded in many different ways in different traditions. Throughout the long history of imperial China, dualism was seen as the complementarity of yin and yang, so that the creation of harmony was the ultimate goal of political authority. In the non-Marxist West, conflict has been viewed as an obstacle, something to be "resolved." Marx and his successors saw conflict as an essential driving force of history, yet they had little to say about conflict once class struggle had been eliminated through revolution.

Mao, however, saw conflict or, to use his own term, "contradiction" as something that would necessarily endure forever. Drawing on traditional Chinese concepts of dualism, he affirmed that there was no thing that did not have its opposite; from the struggle of those opposites, he said, applying the dialectical method, would emerge a new thing, which also would inherently have its opposite. This was not merely a mechanical process, however. Contradictions could be "handled," guided into creative and historically progressive paths by enlightened leaders for whom practice was the criterion of truth. Disorder, which brings contradictions to the fore, was therefore to be encouraged, as the proper vehicle for continuing the revolution. Political organization and mass participation were to be directed toward that end; the alternative, in Mao's view, was the slow death of the revolution in bureaucracy and embourgeoisement.

Without choosing sides between the vision of Mao and that of his moderate adversaries, Starr points out that Mao's theory of perpetual revolution depends for its success on the presence of an almost godlike leader who can direct the titanic forces of disorder to creative ends. Mao died in 1976, and the Chinese revolution changed its course with startling swiftness. In words that have already proven prophetic, the author concludes, "That Hua [Guofeng] or his colleagues will grow to the point of being sufficiently authoritative to be able to carry out Mao's challenging theoretical legacy, and that, having so grown, they will choose to do so, seems highly unlikely. ..." If Mao was right, the revolution cannot but continue, but at this point it is unlikely to continue along the path traced out by his vision.

John Major is an associate professor of EastAsian history at the College.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureConjuring Ethics in the Curriculum at Dartmouth

March 1981 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

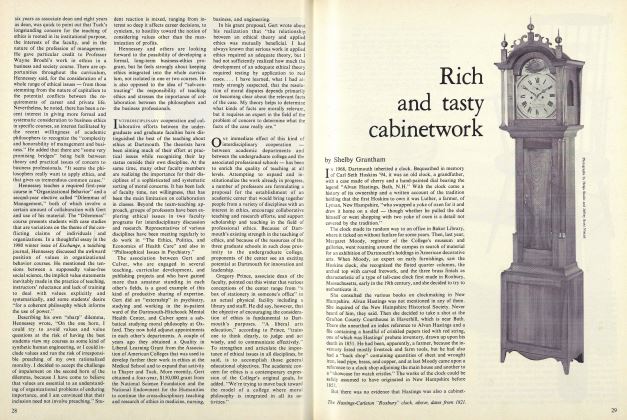

FeatureRich and tasty cabinetwork

March 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

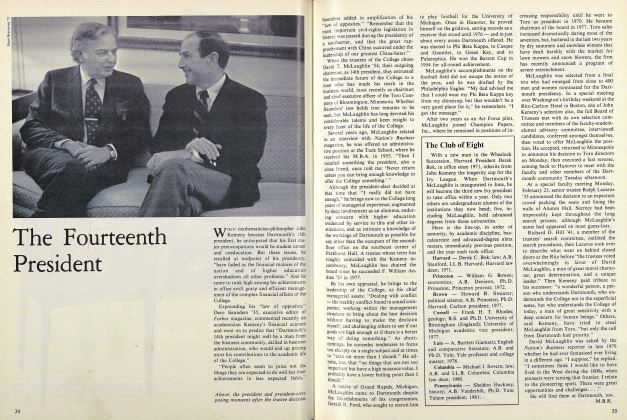

Cover StoryThe Fourteenth President

March 1981 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleImagining Beyond Limits

March 1981 By Don Rosenthal '81 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1948

March 1981 By FRANCIS R. DRURY JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1967

March 1981 By CLEMSON N. PAGE, JR.

John S. Major

Books

-

Books

BooksTen Introductions a Collection

January 1935 -

Books

BooksWHEN WE SKI

April 1937 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Books

BooksPREPOSTEROUS PAPA.

January 1960 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Books

BooksHOW TO ADOPT A CHILD.

JULY 1967 By MICHAEL L. SLIVE '62 -

Books

BooksTHE CHILD-CENTERED SCHOOL

January, 1930 By R. A. B -

Books

BooksAMERICAN SHIPS.

FEBRUARY 1972 By STEPHEN G. NICHOLS JR. '58