China and would-be China

THE footprints could have been Marco Polo's. The traces of the past linger long in a high, cold desert, and as I walked on the caravan track of the old Silk Road, on a cliff above Tunhuang in Chinese Central Asia, I was moved almost to tears by the depth of the past, by the expanse of desert and mountains, and by the first view of China that has greeted travelers from the West for countless centuries. It was my second visit to China in less than a year. We had come out from China proper, ten specialists in ancient Chinese history, traveling 40 hours west of Sian in a first- class sleeper reserved for our private use for a week, breakfasting on crepes suzettes prepared by a Shanghai dining car crew that remembered cooking for foreigners in the old days. The incongruity was almost too much to take.

Continuity and change, sometimes bewilderingly juxtaposed, confront the visitor to China on every hand. My first visit, in March 1978, came as an unlooked-for opportunity. Dean Esserman, a talented and energetic student with a knack for making interesting things happen at the College, had secured an invitation, through his family, to visit China. Knowing a good chance when he sees one, he got permission to bring "a few friends" with him. So Dean Esserman and friends, alias the Dartmouth Student Tour Group, became one of the first delegations of American undergraduates to visit the People's Republic of China.

The group was deliberately constituted to represent the diversity of Dartmouth students. As a matter of principle, any Asian Studies major who wanted (and could afford) to go was eligible; beyond that, department chairmen were asked to recommend promising students to join the group. For me, the invitation to go along as adviser was the fulfillment of a dream, the first chance to visit a country that I had been studying for more than 15 years.

We entered through Hong Kong, crossed the famous foot-bridge at Shumchun and were received by our hosts for the first of many "brief introductions." That briefing set a tone that was to last throughout the trip: earnest, friendly, eager to please. As our train wound slowly toward Canton, we excitedly watched brick villages and lush green paddy-fields worked by purposeful production brigades and fat water buffalo.

Our itinerary took us to Canton and the nearby ceramics-producing town of Foshan; to Shanghai, China's liveliest city; to Soochow, the "Venice of the East"; and to Peking. We were given a good overview of contemporary China in a hectic schedule that had us reeling from exhaustion. We visited the Peasant Movement Institute in Canton, where Mao Tse-tung refined his revolutionary theories as headmaster in 1925; saw temples and gardens, played Frisbee in a Canton park and boated on Peihai Lake in Peking; spent a morning at a Shanghai dockyard, where a group of managers and technicians heatedly denounced the Gang of Four (Madame Mao Tse-tung and three associates, who effectively controlled the Chinese government in the early 19705) and discussed with remarkable frankness the problems caused by past mismanagement. We visited communes near Shanghai and Peking; spent evenings at sports events, acrobatics shows, and Chinese opera; walked the streets unsupervised in every free moment we had; and saw the Forbidden City, the Ming Tombs, the Summer Palace, the Temple of Heaven, and the Great Wall - the familiar splendors of Peking.

Our main focus, however, was on education. We had asked in advance to visit schools, and our hosts took us to educational institutions at every level, from kindergarten to university. China was just coming out of 12 years of the educational chaos of the Cultural Revolution, and the new sense of commitment showed everywhere. Teachers spoke excitedly of higher standards and a new curriculum, and the students' dedication to their studies was obvious. While we were in Peking, posters everywhere celebrated the National Science Conference that was to open in April, another sign of China's commitment to modernization.

The trip was much more than a vacation in an exotic country. We went to China to learn, and our most important experience was of the intense excitement of learning. For some members, the main lessons were political and social. The results of a revolution guided by Mao's vision of Marxism- Leninism were visible everywhere. China is a poor country, and an underdeveloped one; yet we saw no degrading poverty, no evidence of malnutrition or disease, no prostitution, no drugs, no beggars. For others of us, the main lesson was one of a cultural continuity and sense of stability unmatched by anything in the Western experience. For still others, the visual experience was paramount; for example, the historical lessons of 19th- and 20th-century Western influence on the architecture of Canton and Shanghai compared to the expression pression of Confucian, Mandarin self- confidence seen in the formal magnificence of Peking and the informal grace of the gardens and canals of Soochow.

Two weeks were barely enough to give us a breathless first look at China, but our impressions were overwhelmingly favorable. We saw a country that is orderly, purposeful, hard-working, and moral, in ways that sometimes seem like a distant memory in America. Everyone in the group felt strongly the need to understand better that great and ancient country, and some members set about doing so at once. Three members are now in Tokyo, Taipei, and Singapore preparing for careers in international business and Asian affairs, and two others returned determined to commence the study of Chinese as soon as possible.

A couple of weeks before leaving for China, I learned that my name had been mentioned as a possible member of a Han Studies Delegation to China being put together under the auspices of the National Academy of Sciences. I greatly feared that my taking the one trip would make me ineligible for the other, on a share-the-wealth principle; but two days after my return, I learned that I would be going to China again in the fall.

The Han Studies Delegation consisted of ten specialists in the history, philosophy, literature, art, and archaeology of the Han period (206 8.C.-220 A.D.) and two American officials along for the ride. The Academy sends about six delegations a year to China, and hosts six in return. Most are in the applied sciences, but the Chinese had expressed a particular interest in discussing Han studies with a group of American specialists.

The Dartmouth trip in March was what the Chinese refer to as a friendship study tour, designed to give a broad view of contemporary China. The autumn trip, by contrast, was much more narrowly professional, with little emphasis on factories, communes, and schools (making me very glad to have seen such things earlier). Our task was to cement scholarly contacts, and to find out as much as we could in five weeks about what the Chinese had learned since Liberation about the greatest of their early imperial dynasties.

We began our trip with a few days in Peking, getting acquainted with our hosts from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, the Institutes of History and Archaeology, and Peking University, and exploring museums and libraries. Then we left for Loyang, Sian, Tunhuang, Lanchow, Changsha, Kunming, and Chengtu before returning to Peking for a final week of discussions, sightseeing, and book-buying.

For a historian, the trip was an excursion to paradise. In Sian and Loyang, the earlier and later capitals of the Han, we saw the crumbling foundations of palaces and city walls 2,000 years old (sic transitgloria . . . ). In Sian, we also watched the excavation of some of the 8,000 life-size clay soldiers that had been buried to guard the tomb of China's first emperor. At Tunhuang, we were the first Americans in 30 years to see the hundreds of Buddhist cave-temples, decorated with statues and murals, that have been a wonder of Asia for 1,500 years. In Changsha, we visited the excavations at Ma-wang-tui, which produced a wealth of artifacts and texts that has transformed our understanding of early China. Near Chengtu, we saw a large-scale irrigation system that had been built in 250 B.C. and is still functioning and being expanded. We met many Chinese scholars; publications were exchanged, letters promised, and future long-term scholarly exchanges were discussed. These personal contacts were perhaps an even more important benefit of the trip than the opportunity to see first-hand the material .remains of history.

ONE trip to China is wonderful; two, at an interval of six months during a period of profound and rapid change in contemporary China, were more than wonderful twice over, since they provided a chance to make some very striking comparisons. The educational changes that we had heard discussed in March were a reality in October. New university entrance exams had been given, universities were functioning at full capacity and graduate students had been enrolled for the first time since 1966. Just before the Dartmouth group arrived last spring, the National People's Congress made the Four Modernizations (agriculture, industry, national defense, and science and technology) a national goal; by autumn they were a national obsession.

In March, Chairman Mao was still a demi-god, and billboards and slogans all over the country emphasized the legitimacy of Hua Kuo-feng's succession to Mao's mantle. By autumn Mao was a man again; a great and heroic leader beyond doubt, but capable of mistakes, too. ("Raise high the glorious banner of Chairman Mao" was the slogan in the spring; a cynical diplomat is reported to have commented, "They're raising it so high you can't read what's written on it any more.") In the spring we heard many heart-felt denunciations of the Gang of Four; by fall it was clear that the Gang of Four are in part stand-in bad guys for Mao's mistakes, and criticism broadened to include the entire Cultural Revolution, which had had the blessing of Mao himself. In the last few days that we were in Peking in November, critical wall-posters began to go up daily (the right to put them up is guaranteed by the new 1978 Constitution of China), as people began to feel confident that the new atmosphere of free speech could be trusted. We knew that something important was happening.

During neither trip to China did I hear Chairman Mao spoken of with less than total respect. But real love and admiration was reserved for Chou En-lai. That is highly significant for the future direction of China, for in a country where the "mass line" is taken seriously as a means of policy formulation, the mood of the people is of crucial importance. After 1966, Mao and his associates espoused a line of "revolutionary self-reliance" and of ideology over expertise. Chou En-lai is seen as having played the role of a moderate throughout that period, trying in the face of enormous strains to keep the country functioning.

Teng Hsiao-p'ing is the man most closely identified with the social and political revolution - not too strong a word - that China has gone through this year, and as such he is regarded as the heir to and perpetuator of the policies of Chou that the people of China want to see realized: moderation, internationalism, greater social diversity and freedom of expression, progress and modernization, and a more decent life for the people after their decades of revolutionary struggle.

Thus, when China and the United States announced their mutual diplomatic recognition and normalization of relations, a month after I returned home last fall, I was pleased but only somewhat surprised. However, news of normalization was quickly followed in this country by expressions of what I regard as quite unnecessary dismay and concern, focused by debate in the Senate on the "Taiwan question." I would like to explain why I regard most of the fears expressed in that debate as unfounded.

NORMALIZATION of relations with China became official American policy in 1972, with the signing by President Nixon of the Shanghai Communique. In a sense, those who wished to object to the policy should have done so then, rather than waiting for the event itself. Since 1972, normalization has been only a matter of time, and because the U.S. agreed in the communique to a "one-China policy" - that there is only one China, and Taiwan is part of it - it was also inevitable that normalization would come about by the breaking off of U.S. relations with the Republic of China on Taiwan.

For several years, the normalization that had been agreed to in principle could not be put into effect. For the United States, the Vietnam War, Watergate, and the political sensitivity of the Taiwan issue for a new President made it impossible to press the issue. For China, the xenophobia of the Gang of Four in the early 1970s and the deaths of Chou En-lai and Mao Tse-tung in 1976 presented similar difficulties. In late 1978, the right moment arrived. President Carter, in the aftermath of Camp David, was doing well in foreign policy if not domestically, and could afford a risk, while Teng Hsiao-p'ing, seen as the champion of correct policies following the popular revulsion against the Gang of Four, could also afford to be bold.

Yet for America, normalization and the break in relations with the Republic of China were not without trauma. The regime on Taiwan was an old and familiar ally (though one discredited in the opinion of most historians and in the eyes of most of the world), and many thought it an act of bad faith to break a treaty of such long standing. I would argue that the Republic of China was lucky, beyond any reasonable expectation, that America for so long lived in a dream-world in which Chiang Kaishek, and then his son, were thought to govern China. It seems to me that the recognition of reality, however distasteful it might be to some, is a first prerequisite of a foreign policy that seeks to promote a stable world order.

I think, in fact, that a principal benefit of normalization will be the discrediting of the Nationalist government on Taiwan, paving the way for its replacement by something better. It is important to recognize that the Nationalist regime governs Taiwan as an alien force. Taiwan has a long history of semi-autonomy; it has not been effectively ruled by any government based on mainland China since 1895. When Chiang and his defeated army arrived on Taiwan beginning in 1947, they were unwelcome intruders. Out of a population of 17 million on Taiwan, only some 2.5 million are of recent mainland origin yet that minority rules, through a one- party, undemocratic government (modeled on that of the Soviet Union) that has suppressed human rights through martial law for 30 years. Our "democratic ally, the Republic of China" has always been something of a myth. Withdrawal of U.S. recognition will remove one of the strongest bulwarks of minority government on Taiwan - the claim that the government is that of all of China, temporarily in exile in a single province - and allow the Taiwanese a much greater - opportunity to govern themselves.

James Thompson, head of the Nieman Foundation at Harvard, proposes the following analogy: Suppose that, at the end of the American Civil War, Jefferson Davis and his government retreated to Puerto Rico, and, backed by Great Britain, claimed to be the legitimate government of all of the United States. Such a claim would not only have been absurd, but also highly oppressive, uncomfortable, and dangerous to the people of Puerto Rico. Yet we have contributed to the maintenance of such a situation on Taiwan since 1949. Now, at last, we acknowledge that whatever the situation on Taiwan, its government is not that of China. What will happen to Taiwan? What can we do about it?

My own preference would have been for a plebescite on Taiwan to allow the people there to determine their own future: continuation of the Nationalist government, reunification with the mainland, autonomy under Chinese sovereignty, independence. But our agreement to the "one-China" principle in 1972 has excluded that option. If the people of Taiwan should decide that they do not want to be part of either China, there is not much we can do to help them.

Will we, in the Gothic words of a New Hampshire newspaper publisher, "abandon the people of Taiwan to the yoke of Chinese Communist slavery?" No. First of all, because no such thing exists, except in the nightmares of the American far right. China is a far more decent society in which to live than many, many others in this world. Secondly, because China does not have now and will not have for many years the military capacity to impose its government on the people of Taiwan. The Nationalist army, made up mostly of Taiwanese troops, probably never would have fought to regain the mainland, but they would fight fiercely to defend their own island. The cost to China would simply be too great. Reunification will come, when it does, only when China makes it attractive enough to Taiwan.

But, one might reply, Teng Hsiao-p'ing has repeatedly refused to renounce the use of force in dealing with Taiwan. Quite naturally. China claims the right to defend Taiwan as a part of its sovereign territory. China would certainly oppose an armed attack by the Nationalist regime, or an armed attempt to declare independence. The United States did not, after all, renounce the use of force when threatened by the secession of the South. Also, there is a remote possibility that the Nationalists would be tempted to "play the Russian card" in a last-ditch attempt to gain an ally to its cause, and if they did so, they would create an intolerable situation that China would have to oppose. But failure to renounce the use of force is not the same thing as a threat to use force. In any case, should China quite irrationally attempt the military conquest of Taiwan, it is unlikely that the United States would remain an idle bystander, even in the absence of a mutual defense treaty with the Republic of China. Meanwhile, it is reassuring that "reunification" has replaced "liberation" in Chinese rhetoric about Taiwan.

As I write this, China is engaged in a military adventure in northern Vietnam, the motives and outcome of which remain unclear. That action has certainly created new American nervousness about China's willingness to use force to recover Taiwan. I think it would be a mistake to regard the two situations as comparable.

The action against Vietnam is basically part of China's anti-Soviet foreign policy, designed to warn Vietnam against being a Russian proxy as an "Asian Cuba"; and to punish the Vietnamese for incidents along the Yunnan border, for mistreatment of the Chinese ethnic minority in Vietnam, and for the invasion of Cambodia. It might also be seen as a way of giving America an object-lesson in "standing up to the Russians," and perhaps as a sop to orthodox Maoists in the Chinese high command in return for their support of Teng's policies of rapid modernization and social change. A limited incursion a few miles into Vietnam's northern highlands, for potentially significant political, gains, must have seemed very tempting to the Chinese, however risky, ill-conceived, and outrageous it was regarded by their American friends.

Unlike Vietnam, Taiwan is for China a matter of domestic policy. The political, economic, and military cost of a full-scale invasion and war of conquest against that well-defended island would be very high, and the only gain - recovery of a province now under Nationalist rule - is something that China expects will happen naturally over time anyway. A border war with Vietnam is a most unlikely model for China to follow in formulating its policy toward Taiwan. One may regret China's aggressiveness in Vietnam, and the warnings and concern officially expressed by the United States are entirely appropriate; but the effect of that situation on the normalization of U.S.-China relations and the status of Taiwan should be minimal.

Some members of Congress have expressed the hope that official relations with the Nationalist government should continue in some form. Could we continue to have an embassy or consulate in Taiwan even as we recognize the People's Republic of China? Emphatically not, because neither claimant to the government of China would stand for the situation. The only thing that both agree on is that there can be only one government of China, and so we must choose. We can only have official relations with one. The officially unofficial organization that will replace our embassy in Taipei is about our only option.

What I suspect will happen with Taiwan is what is now being called the "Hong Kong formula." Given time and sufficient inducements (and the realization that there is, in the long run, no other way out), the Nationalist government will proclaim its own demise. The Nationalist flag will come down, the People's Republic flag will go up, and not much else will change; Taiwan, formally reunited with China, will continue with business as usual as a Chinese Autonomous Province, while both sides sit back and wait a few decades (one can afford patience in a culture with so many centuries of history) to see what happens next. The Taiwan independence movement, if it persists, will complicate this scenario, but that is unpredictable and largely outside our control. The only solution to the Taiwan question is time, and time will bring a solution if no one rocks the boat in the interim.

What do we gain from normalization? Many things, at little cost except to our illusions. We gain a powerful ally, and one with great credibility among Third-World nations, in our efforts to oppose Soviet expansionism and troublemaking around the world. In an era of chronic huge deficits in American international trade, we gain access to a huge market - not for luxury cars and household gadgets (and one must beware lest mercantile hopes rise too high), but for science, technology, and industrial goods. Most importantly, we gain renewed friendship with an optimistic, creative, and hard-working people from whose modern and ancient culture we can learn much about harmony, cooperation, and community-mindedness, philosophy, letters, and the arts.

Most recent visitors to China have been profoundly moved by seeing a people create, on ancient foundations, a revolutionary new society as valid and far- reaching for its people and for this century as the American revolution was 200 years ago - a society that draws inspiration from our own and desires friendship with us. A further benefit of normalization is that increasing numbers of Americans will soon be able to have that experience.

Two years ago, I reported in these pages on the frustrations of an unsuccessful attempt to gain permission for a Dartmouth Alumni College visit to China. I wondered for a long time about where we had gone wrong in that attempt. Now it appears that we were just trying a bit too soon; we knocked on the door before it was quite ready to open. Things have changed greatly since then, and I think that much better news is coming for those who shared our disappointment last time.

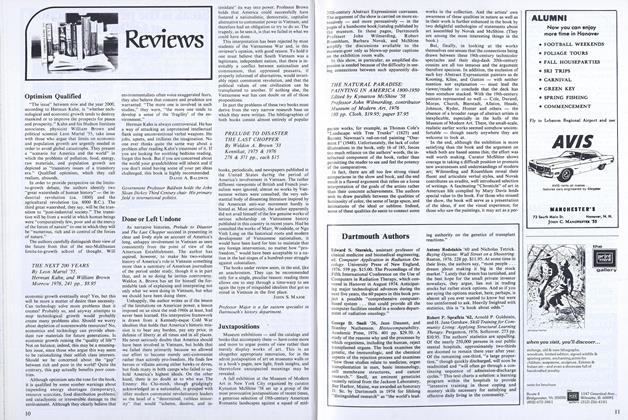

The varieties of self-expression: GregWajnowski '79 (above) hand-stands on theGreat Wall, and a dancer in Yunnan hilltribe costume practices in a Kunming park.

The varieties of self-expression: GregWajnowski '79 (above) hand-stands on theGreat Wall, and a dancer in Yunnan hilltribe costume practices in a Kunming park.

A statue of Mao on the main square of Chengtu. The full slogansays: "Unite and struggle to meet the responsibilitiesof a new age." At left, the ancient stone figure of ageneral guards the avenue leading to the Ming tombs in Peking.

Two young girls, whose generation willknow the meaning of today's change, posedfor their picture on a Shanghai commune.

Striking the figure of a "revolutionaryworker," this farmer was tending paddieson a rice-growing commune near Canton.

John Major, assistant professor of history,specializes in East Asian affairs. He hasbeen a frequent participant in AlumniCollege and Dartmouth Seminarprograms.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturePilgrims' Progress

April 1979 By L. Bruce Anderson, Edward Bradley -

Feature

FeatureA winter of discontent, a day of perceiving differences

April 1979 By Shelby Grantham -

Article

ArticleJust Out of Reach

April 1979 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleBooks in Process

April 1979 -

Article

ArticleMoney Man

April 1979 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleOn the Raising of Spirits

April 1979 By MICHAEL DORRIS

John S. Major

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe 1961 Alumni Awards

July 1961 -

Feature

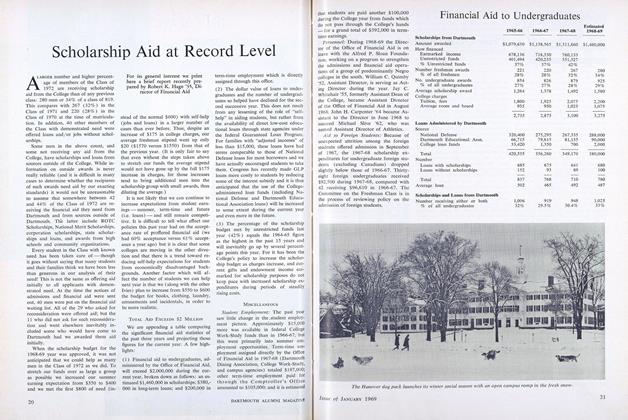

FeatureScholarship Aid at Record Level

JANUARY 1969 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryChris Miller '97

OCTOBER 1997 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

Cover Story

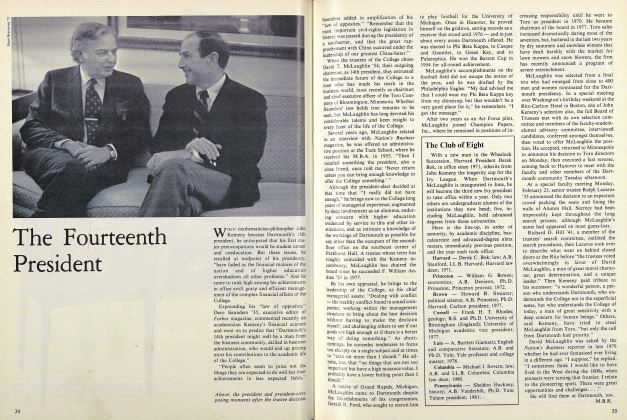

Cover StoryThe Fourteenth President

March 1981 By M.B.R. -

Feature

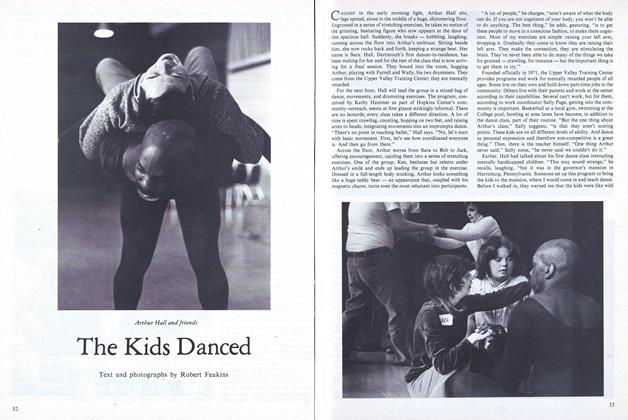

FeatureThe Kids Danced

September 1979 By Robert Feakins -

Cover Story

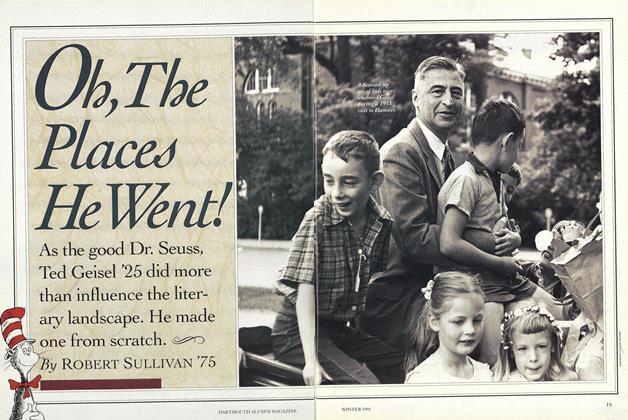

Cover StoryOh, The Places He Went!

December 1991 By Robert Sullivan '75