DESPITE all that has been said and written concerning academic tenure and its place in education, there appears to be little understanding, and not really very much appreciation, of the system in some segments of our society. There are intelligent and well-meaning individuals both inside and outside the academic community who argue forcefully for abolition of tenure. For the most part, their arguments appear to me to be based on incomplete information concerning tenure and a distorted view of what it is intended to accomplish. To them, tenure is a mechanism for insuring that the incompetent, "over-the-hill" faculty member will

retain his or her position until retirement. They adhere to the aphorism that "those who are good have no need for tenure; those who have need for tenure are no good." Critics also contend that the tenure system creates other problems. They say it fosters faculty laziness and irresponsibility, perpetuates the academic status quo, limits new approaches to education, prohibits the retention of younger and brighter scholars, and, in times of economic stress, creates a financial burden for the institution. Certain of these criticisms, but by no means all of them, are valid. However, a careful analysis reveals that some of the problems are not due specifically to the tenure system but to internal institutional procedures.

It is not my intention here to answer all the criticisms that have been leveled against tenure. My purpose is merely to provide a personal view of the system from the perspective of someone with more than 20 years as a faculty member and one who has given serious thought to the system and to alternatives. The tenure system certainly requires some explanation (defense?) in light of current financial constraints on institutions of higher learning and projected future costs to run our colleges and universities. Alumni have a large stake in keeping these institutions afloat, and they should be better informed on the tenure issue.

What is most distressing to me is that many of the critics of the tenure system fail to comprehend why faculty members are granted special rights of academic freedom in the performance of their professional duties. Perhaps if they better understood the intimate and often complex relationships that exist between faculty obligations to the educational system and the responsibility of society to the institution and the institution to its faculty, some of the criticism would diminish.

Almost everyone would agree that the primary obligations of faculty members in colleges and universities are to teach, engage in scholarly research, and share with administrators and others in the overall educational activities of the institution. In fact, the obligations of the faculty are much greater. Faculty members not only teach, they must teach the truth; they not only engage in research but must search for the truth. It is really this idea of pursuing and teaching truth ― the truth as scholars perceive it in their disciplines ― that is one of the basic principles on which our modern educational institutions were established.

This concept is so basic that even under autocratic and repressive government regimes the academy has usually, though unfortunately not always, been accorded autonomy. Indeed, the self-governing nature of our colleges and universities has contributed much to their success and longevity. Even the severest critics of tenure would support the doctrine that there should be minimum interference with the educational activities of the institution from outside influences. In this case, institutional freedom must be translated to include freedom that faculty members require in exercising thought, judgment, and action. I believe there is no institutional freedom if faculty members are in any way constrained in the exercise of their professional obligations.

When professionally qualified individuals are appointed to the faculty at most institutions of higher learning they are accorded certain rights and privileges. The rights of freedom of expression and freedom of inquiry are among the most important to the scholar since these give license to extend the boundaries of knowledge wherever they lead. Furthermore, these rights give the scholar liberty to champion unpopular ideas and to investigate and propose unconventional solutions to problems. Unlike constitutional rights, which are guaranteed by law, the rights of the faculty are acquired rights, and there is no judicial system that guarantees them to an individual. How then are these essential rights to be preserved and protected?

The most obvious method is to guarantee security in an academic appointment to selected faculty members. This is usually done either by awarding a contract with a specific time limitation (limited tenure) or by granting permanent tenure. The contract system is used by many two-year and some four-year colleges and usually provides faculty with short-term appointments. In many institutions where contract systems are employed, faculty members have organized to bargain collectively to secure professional rights and benefits. Unionization of faculty members is no longer rare on the college campus. It is interesting to note that in institutions where faculty unions have gained strength, they have negotiated permanent tenure agreements. Lionel Lewis, in his book Scaling the Ivory Tower, has observed that often in these cases "tenure is redefined as entitlement to permanent employment, not as a measure devised to advance the search for the truth." It is an important distinction.

Most four-year colleges and almost all universities have adopted the permanent tenure system. Under this system, initial appointment for beginning faculty members is for a fixed term, usually with the opportunity for renewal. These appointments provide a probationary period, ordinarily not more than seven years, dur which critical evaluation of the individual takes place. The probationary period is a time during which the individual develops his or her professional skills. Obviously, evaluation procedures differ among various institutions and, regrettably, there are no uniform or accepted procedures applicable to all situations. Nevertheless, where various constituencies of the academic community ― faculty, students, and administration ― share in the responsibility for faculty evaluations, the selection procedure is most likely to lead to the retention of individuals of superior intellect and integrity.

Of these two common systems for appointing and retaining faculty, it is the permanent tenure system that gives maximum assurance that faculty rights will not be compromised. While the tenure critics may still argue the point after this discussion, I remain convinced that faculty rights and tenure are practically inseparable. I cannot conceive of how the faculty in certain academic institutions could, or in some cases would, exercise their professional rights in the absence of permanent tenure. If a faculty can be coerced, intimidated, or threatened with economic sanctions by forces in the academy or in society at large, it cannot function effectively. If members of a faculty are restricted in the complete and free use of their intellectual abilities, then it is the students who suffer immediately and the educational institution that is harmed in the long term.

In addition to academic freedom, there is a more subtle but equally important kind of freedom that individual faculty members derive from permanent tenure. This is the freedom to disagree openly with opinions held by faculty colleagues and administrators, the freedom to be nonconforming, and even the freedom to be eccen- tric providing, of course, that the individual's behavior does not interfere with the performance of professional tasks. John Kemeny, in a brief statement on tenure prepared several years ago, came directly to the point when he wrote, "It is freedom from coercion by the administration and colleagues within the department that tenure really buys." Tenure should not be thought of as a mechanism that protects faculty members from internal pressures and criticism. Although it is true that tenured faculty cannot be dismissed without adequate cause, their differing views are not always respectfully acknowledged by colleagues. Even in distinguished institutions, there are reports of senior faculty members who are harassed and ostracized because they adhere to ideologies that some intolerant colleagues and administrators find threatening. Tenure does not buy freedom from this kind of abuse. Fortunately, these situations are not common, but where they do occur these actions demean the academy and violate academic freedom and the dignity of the profession.

The question naturally arises whether the non-tenured faculty share the same freedoms as their tenured colleagues. Theoretically, they do. Most institutions where the tenure system is practiced proclaim that faculty on term appointments enjoy the same rights of freedom of expression and action as their permanently tenured counterparts. Actually, however, non-tenured faculty are frequently cautious about expressing views contrary to the opinions held by a majority of senior members in their department or academic unit. This might not be the situation if senior faculty members were aware that their collegial responsibilities include maintaining academic values and protecting the rights of their non-tenured colleagues. Academic administrators should be alert to recognize when violations of faculty freedoms have occurred and quick to assert that, regardless of the tenure status, no abridgement of faculty rights will be tolerated. But, as Lionel Lewis has indicated, administrators "do not have an impressive record of protecting academic freedom." At present it is unfortunate, but I think true, that freedom to dissent within the academy sometimes requires the force of permanent tenure to prevent serious retribution.

It is time academic institutions recognized that the tenure system, with all its positive attributes, may not be functioning adequately for all members of the faculty. One fact should by now be clear: the tenure system was adopted primarily to protect faculty rights to academic freedom and to insure due process in dismissal proceedings. There is no question in my mind (and the documented record of activities of the American Association of University Professors supports my contention) that tenure functions effectively in doing what it is supposed to do. If, as we now find, it does not solve other problems of present-day academia, then it should be strengthened, not condemned and discarded.

In recent years much attention has been given to ways institutions could improve their tenure policies, and many worthwhile and explicit recommendations have been proposed. From my viewpoint, the major obvious weakness of the system is that it does not provide adequate guidelines to safeguard the freedoms and, more importantly, the careers of probationary faculty members. It is in this area that institutions must provide the leadership. The prospects of fewer new positions becoming available in colleges and universities in the next two decades, combined with the current realities of fewer tenure openings, make it necessary for institutions to direct their attention and some of their resources to the professional needs of the non-tenured faculty.

Consideration could be given immediately to extending probationary appointments and making more imaginative use of temporary and part-time faculty appointments. But what I think is most important is the initiation of a faculty development program to avert the sense of anxiety and the slaughterhouse mentality that my colleague Peter Travis describes so vividly below. The program could provide for the continuous evaluation of qualitative and quantitative aspects of professional service. For example, various senior faculty members could assist in the professional development of new faculty colleagues. Certain members of a department could regularly audit classes taught by junior faculty, provide thoughtful critiques of their performance, and participate in the continuous development of their teaching abilities. Other senior faculty could be expected to provide assistance and guidance to new faculty members in initiating or continuing their research or other scholarly activities. With an organized program even more could be done, and the probationary faculty member would be regularly apprised of his or her performance in those areas that the institution considers important. Moreover, the junior faculty member would acquire a better understanding of the criteria on which a judgment for tenure will be based. The essential point is that development of junior faculty is almost totally neglected in institutions of higher learning or, at best, is a casual undertaking. The academy would be well served in both the short and long term if faculty development programs were a recognized part of the tenure system.

There are also reasons for including permanent faculty members in a faculty development program. The expansion of faculties during the fifties and sixties, coupled with recent changes in the mandatory retirement age, will result in our colleges and universities being staffed by an older faculty in the coming decades. No one knows for certain how this will affect academic institutions, but there will be a reduction in the number of appointments usually available to young faculty. Except for some administrative hand-wringing and lamenting about the state of affairs, there has been little constructive thought given to this development. It seems obvious that the experience and maturity of an older faculty could have significant benefits for some institutions. Concerns expressed over how research productivity in academia will decline with an older faculty should be dismissed, since recent evidence from several studies on age and productivity in various academic disciplines fails to support a simple negative relationship with age. The real problems associated with an older faculty will be that with increasing age some individuals may want a more flexible academic schedule than the traditional 9 to 12 month appointment now permits. Others, after a number of years' service, may require considerable free time to update their teaching or research skills. Still others may need longer periods of time than are now provided to recover from fatigue associated with a full term of professional activities. And still others may find after years of teaching and research that they would like to change academic fields or even move into academic administrative positions.

One can imagine additional accommodations that institutions may be asked to make for their faculties. It appears to me that an innovative program for faculty development should explore the full range of possibilities available for the continued and maximum use of the talents of the faculty. Imaginative programs that answer the needs of an older, permanent faculty could even provide the means for bringing younger faculty members on the scene. When we see young, gifted faculty members becoming expendable commodities in the academic market place, it is not the tenure system per se that will have failed. The failure will be due to a lack of deliberate action by our academic institutions.

In most ways permanent tenure is a derived system that benefits the institution. There is no question that during the probationary period it is an incentive for non-tenured faculty members to demonstrate to colleagues and administrators that they are promising teachers and scholars of the highest quality. It provides for a system of vigorous review of young faculty that should insure that only the most qualified individuals are retained. It is an important device for attracting to colleges and universities outstanding scholars who wish to pursue their professional careers in a secure environment and in the company of other scholars. In addition, when men and women can look forward to a permanent, long-term association with the college or university they are willing to assume increased responsibility for the educational enterprise. As John Kemeny has said, they become "partners" with the administration and share accountability for the educational activities of the institution.

The critics of academic tenure still may not be convinced by this brief summary that the system, with or without improvement, is important for maintaining academic excellence in higher education. They may contend that there are other systems, most not adequately tested, that could replace tenure. The development of these alternatives should be encouraged. However, in assessing the efficacy of any new system, all who value the traditions of higher education should look to the capacity of a new system for insuring the most precious of faculty rights: academic freedom.

DeMaggio: "I believe there is no institutional freedom if faculty members are in any way constrained in the exercise of their professional obligations."

Travis: "When I got tenure . . . there was relief, horror, pity- but no sense of triumphant joy. ...I had just been rewarded by a system that was unjust."

Tenure: "an arrangement under which faculty appointments in an institution of higher learning are continued until retirement for age or physical disability, subject to dismissal for adequate cause or unavoidable termination on account of financial exigency or change of institutional program." Commission on Academic Tenure,American Association of Colleges andthe American Association of University Professors

A. E. DeMaggio, professor of biology, relinquished a tenured appointment at Rutgers University to join the Dartmouthfaculty in 1964. He was awarded tenurehere two years later.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureQuestion: Who are the Arts for and, Indeed, Who Owns Dartmouth?

April 1981 By Peter Smith -

Feature

FeatureTenure: the tragedy of the slaughterhouse

April 1981 By Peter W. Travis -

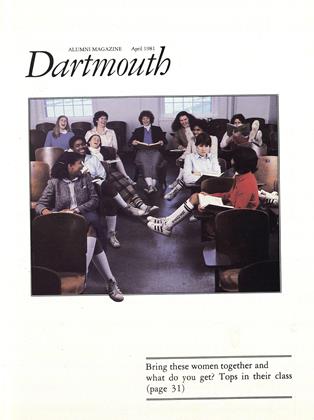

Cover Story

Cover StoryTops in Their Class

April 1981 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryChargé d'Affaires

April 1981 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryBeethoventorte

April 1981 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryGoing Places

April 1981

Features

-

Feature

FeatureMaster Translator

APRIL 1968 -

Feature

FeatureFive Wishes for America

By BENFIELD PRESSEY -

Feature

FeatureBIG JUMP

Winter 1993 By David Bradley ’38 -

Feature

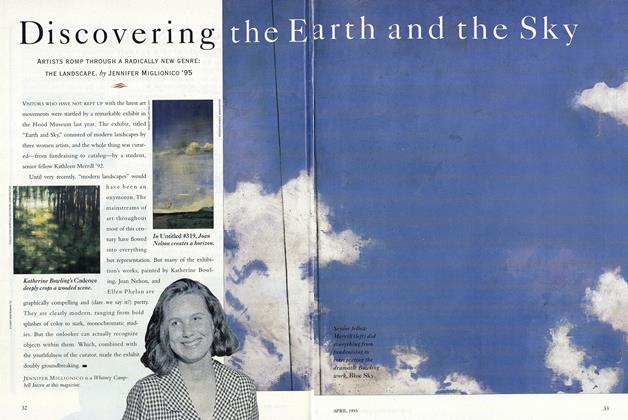

FeatureDiscovering the Earth and the Sky

April 1993 By Jennifer Miglionico '95 -

Feature

FeatureFloating Home

June 1992 By Jim Collins '84 -

Feature

FeatureAn Unease on Webster Avenue

APRIL 1978 By Mark Hansen