Student fees, in annual defiance of the old saw about what goes up inevitably coming down, go nowhere but up, this year for the first time breaking the five-digit barrier. In the academic year 1981-82, for a typical fall-winter-spring-term sequence, students at Dartmouth will pay an average $10,033 for tuition, room, and board, an increase of 15.4 per cent over this year. In painful contrast, the same charges came to $4145 only a decade ago.

The increase set by the Board of Trustees at its February meeting is the largest in a series that has pushed the traditional-year fee up 142 per cent in ten years, but the $10,033 figure is still about average for the Ivy League ― with Harvard leading the pack at $10,500. College officials are quick to point out, however, that Dartmouth's requirement of only 11 terms instead of the more usual 12 brings the average annual rate ― one fourth of the cost of the total four-year curricular pie ― to $9,080, lower by a considerable margin than any other Ivy cost.

Charges vary with the individual student's pattern of terms in residence and off campus. Tuition rates for summer term next year will be $2,025, compared with $2,350 for fall, winter, or spring. Average room rates will be $358 for the summer, $445 for each of the other three terms. Board will cost $494 in the summer, $564 in the fall (with $51 added for freshman week), $535 in the winter, and $549 in the spring term.

Each year, as costs have risen, funds allocated for financial aid to students unable to pay them out of pocket have kept pace with the increase. But next year, the financial-aid budget has been raised far beyond the ordinary to compensate, as financial-aid director Harland Hoisington '48 puts it, for "the double-barreled impact" of rising college expenses coupled with anticipated cuts in federal funds to help allay them. Of three components of a typical payment package, the self-help part ― work-study, dining-hall employment, and so on ― has been raised by a slightly smaller percentage than the tuition-boardroom increase; expected parent contributions in fairly direct proportion; the College's scholarship component by a full one-third.

It was still not clear at mid-March how much of the Reagan administration's program to cut aid to education would make it intact through the congressional gauntlet, but Dean of the College Ralph Manuel '58 said that "our best estimate is that the College will lose $300,000 annually." He declined speculation on which segment of the student population ― economically disadvantaged, middleincome, or comparatively affluent ― might be hardest hit, suggesting that the impact would probably be felt across the board. Eligibility requirements for needbased programs ― Basic Educational Opportunity Grants, now called Pell Grants ― would be tightened severely by eliminating the automatic cost-of-living increase in calculating what a family could afford, lowering the ceiling on grants and raising the percentage of disposable income a family would be required to spend before eligibility could be established. Some of these cuts can be accomplished by regulation alone, without congressional approval, Hoisington explained. He expects that work-study programs and supplementary educational opportunity grants will not be significantly affected, but that National Direct Student Loans may be cut by a third.

Cuts will be most severe, he suggests, in grants not based on need: Social Security survivors' benefits and Guaranteed Student Loans, on which the government has paid the interest until six months after the recipient leaves school. If the administration has its way, the student will have to demonstrate need, parents will pay prevailing rather than low-interest rates on amounts they borrow, and interest on student loans will accrue, adding probably 25 per cent to the amount that must be repaid within ten years. The new requirements would eliminate 80 to 90 per cent of government-guaranteed loans, the National Association of Student Financial Aid Administrators has estimated.

The Chronicle of Higher Education takes a gloomy view of the impact on colleges across the country, suggesting that proposed cuts might force 750,000 students out of school entirely, and a like number out of more expensive and into less costly colleges and universities.

In jeopardy at Dartmouth is the policy of "need-blind" admissions, by which applicants are admitted or rejected without consideration of whether they will or will not need financial aid. Once a student is accepted, his or her requirements are met with various combinations of work, grants, and loans. A policy prevailing in only about a dozen institutions in the country, it has been in force for about ten years and will remain in force, Manuel and Hoisington agree, for the class to be accepted this month. Starting with the class of 1986, Hoisington sees a potential gap between needs and resources to meet them. "There may be a waiting list for scholarships," he says.

President Kemeny is fond of remarking that, quite literally, 100 per cent of Dartmouth students receive financial aid, since even $10,033 ― as astronomical as next year's tuition, room, and board charges seem ― will miss by well over half paying the actual cost of an average year's education at the College. The most affluent student, he points out, is still subsidized by other sources of revenue: endowment income, annual giving, gifts for current use, government and foundation support, ticket sales, and so on. But, beyond that blanket dependence on income other than student fees, 35 per cent of students at the College are on Dartmouth scholarships, 45 per cent on some kind of need-based aid, and probably 80 per cent receiving help in the form of loans. A comparative few pay as they go.

That these figures will change seems certain. Who gets hurt when by how much remains to be seen.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTenure: an academic necessity

April 1981 By A. E. DeMaggio -

Feature

FeatureQuestion: Who are the Arts for and, Indeed, Who Owns Dartmouth?

April 1981 By Peter Smith -

Feature

FeatureTenure: the tragedy of the slaughterhouse

April 1981 By Peter W. Travis -

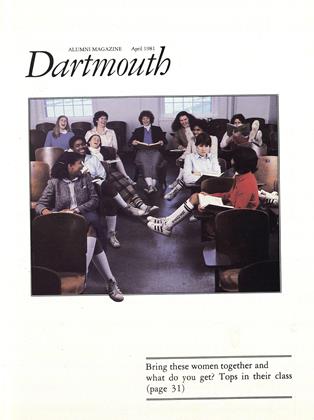

Cover Story

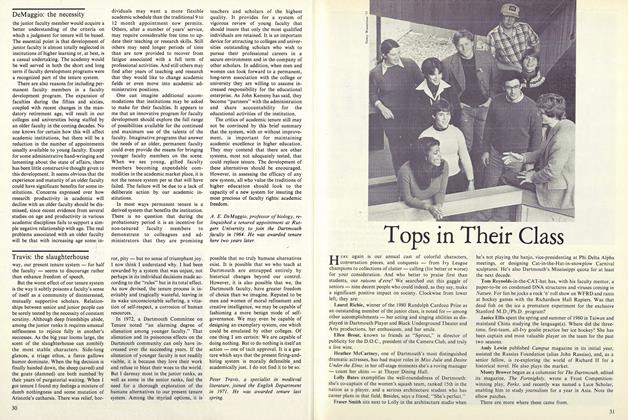

Cover StoryTops in Their Class

April 1981 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryChargé d'Affaires

April 1981 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryBeethoventorte

April 1981