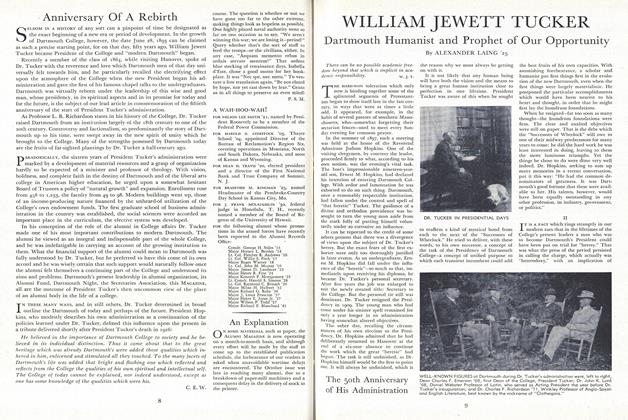

We received the following report from Randy Atherton, Cornell '44, about Dartmouth's contribution to the 1980 Ivy/Ensenada Regatta, a prestigious Southern California sporting event for Ivy League alumni held in conjunction with the annual Newport Beach-to-Ensenada yacht race:

By the end of the second year it was obvious to all members of the Rudder Committee (felt to be a more apt and descriptive designation than the erstwhile "Steering Committee") composed of all team captains plus the commodore and vice commodore that we had a very live, vibrant thing here in this annual Ivy League-to-Ensenada junket. Something was missing, however. We lacked the one ingredient that would indisputably brand the exercise "Ivy League." We needed a tradition! As serious or ludicrous as it might be, we had to have the thread of perpetuity that transcended the imminent party functions and bestowed the warmth of tradition on the whole process.

But where does one go in search of a tradition for an event that is scarcely three years old; barely out of its cradle of infancy? Where else, indeed, but to the stalwart crew of dear old Dartmouth, defenders of the green, forever to be in our esteems one and all! And how did this miraculous happening this provision of an instant tradition occur at the precise moment in time to fill the gaping void? Well, the story has been told in several versions and in quick succession, from those who claimed to be close-range observers to second- or third-hand accounts. The ones who seem to be unanimously silent on the matter are the Dartmouth crewmen themselves, who muttered some question about the wisdom of acquiring crew menbers from other overloaded boats, but would neither confirm nor deny fine details. So we have had to piece together in final compilation a tale that goes something like this:

1980 being one of the slowest races in New-port/Ensenada history, many boats were still out at nightfall, creeping painfully into port (one skipper reported five hours to traverse the last mile!). Toward dusk, and still some five miles from the finish line at Ensenada harbor, the Dartmouth crew was bemoaning this turn of fate, as were all of the other boats around them, when someone on board casually remarked that even though everyone was becalmed, other boats were slowly but surely passing Dartmouth. The comment was noted and another beer can was opened. A few moments later someone else pointed out that even though it was feasible that another boat might drift past them, all the boats could not simultaneously begin to drift by. The profundity of this observation was acknowledged when a bit of paper tossed, overboard floated from stern to bow. Certain credence was lent to the conclusion that they were not moving!

A boat hook swept around under the keel from over the stern encountered some foreign object and repeated attempts failed to dislodge it. Pulling on it poled the boat back upstream so to speak so that enough of the obstruction. could be brought to light to determine that it was a rope, probably attached to some Mexican fisherman's lobster pot, and that it was fouled around the propeller shaft. Repeated attempts to free the vessel failed, and with approaching darkness the question was put to a vote: Should they start the engine and try to dislodge the culprit (thereby disqualifying themselves in the race) or wait it out for some outside help? It was decided that they were by now probably too far down the list to be a serious race contender anyway, and any help that arrived probably would not speak Dartmouthese or worse, might be the owner of the lobster trap. This could lead into all sorts of damaging confrontations so, "Start the engine!"

Order given, she was cranked over and began to percolate. This tack was quickly abandoned after the second or third spurt, however, when the bow began to assume a ridiculous angle and the stern was winched to a point of shipping water. (This has to have been either the heaviest lobster trap or the largest lobster in history!) Straws were drawn to determine a volunteer to swim under the boat with a knife and free the whole project. Such was done and Dartmouth crept to an uneventful docking in the harbor. Uneventful? Yes, but history had been made! There was no way of avoiding the questions of casual observers who witnessed the whole episode, and thereby the inevitable accounting to the committee, and so a dozen silent, downcast, and embarrassed crewmen proceeded to bring up the rear at the evening's dinner at the hotel.

When this story was told at the commodore's party and subsequently circulated throughout the fleet, it. fired imaginations to the point where the Rudder Committee had to take notice and, astutely recognizing an unanticipated gift for their tradition project, they grabbed on hard and fast. They unanimously voted an appropriation to purchase a genuine lobster trap and have it suitably surmounted by a brass plaque engraved "DARTMOUTH LOBSTER TRAP TROPHY." It will henceforth be awarded annually to the boat coming in last, by all standards.

The entire Ivy/Ensenada Regatta owes a profound and lasting debt to the stalwart sons of Dartmouth who came through with the solution when all the committee had was the problem. Besides, they have contributed to each and every sailor who knows so well that some day he may be the one standing there to warmly and tenderly receive acknowledgment that, even though the gods were not with him this time, somebody knows he sailed his heart out!

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTelling Another's Tale

May 1981 By Gregory Rabassa -

Feature

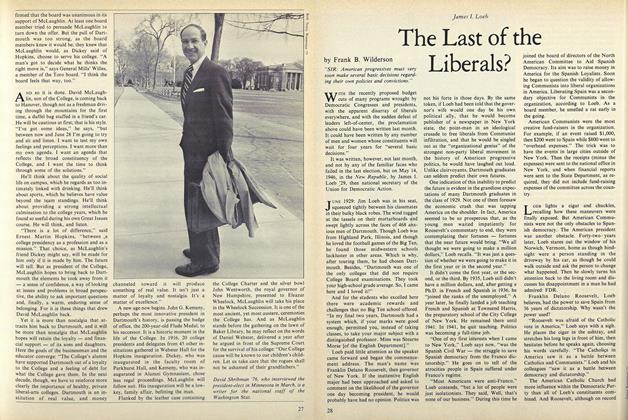

FeatureThe Last of the Liberals?

May 1981 By Frank B. Wilderson -

Feature

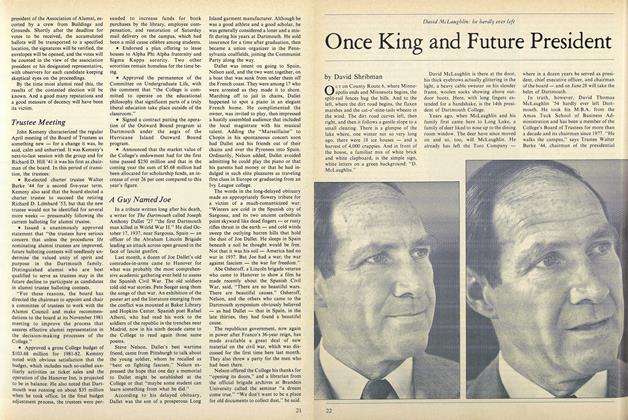

FeatureOnce King and Future President

May 1981 By David Shribman -

Article

ArticleMind for Adventure

May 1981 By Don Rosenthal '81 -

Article

ArticleGreat Issues, Etc.

May 1981 -

Sports

SportsThe Club Set

May 1981 By Brad Hills '65