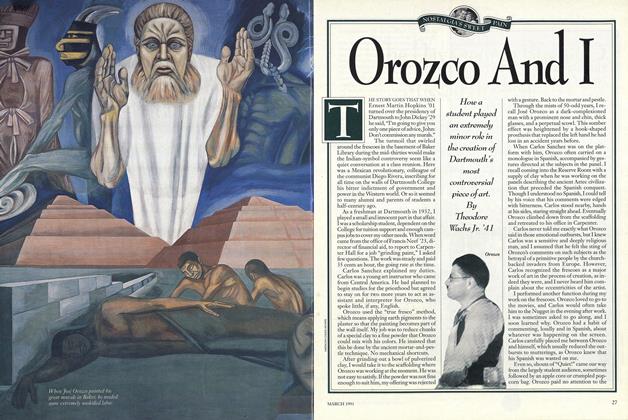

James I. Loeb

"SIR: American progressives must verysoon make several basic decisions regarding their own policies and convictions."

WITH the recently proposed budget cuts of many programs wrought by Democratic Congresses and presidents, with the apparent disarray of liberals everywhere, and with the sudden defeat of leaders left-of-center, the proclamation above could have been written last month. It could have been written by any number of men and women whose constituents will wait for four years for "several basic decisions."

It was written, however, not last month, and not by any of the familiar faces who failed in the last election, but on May 14, 1946, in the New Republic, by James I. Loeb '29, then national secretary of the Union for Democratic Action.

JUNE 1929: Jim Loeb was in his seat, squeezed tightly between his classmates in their bulky black robes. The wind tugged at the tassels on their mortarboards and swept lightly across the faces of 468 anxious men of Dartmouth. Though Loeb was from Highland Park, Illinois, and though he loved the football games of the Big Ten, he found those midwestern schools lackluster in other areas. Which is why, after touring them, he had chosen Dartmouth. Besides, "Dartmouth was one of the only colleges that did not require College Board examinations. They took your high-school grade average. So, I came here and I loved it!"

And for the students who excelled here there were academic rewards and challenges that no Big Ten school offered. "In my final two years, Dartmouth had a system which, if your marks were good enough, permitted you, instead of taking classes, to take your major subject with a distinguished professor. Mine was Stearns Morse [of the English Department]."

Loeb paid little attention as the speaker came forward and began the commencement address. The man's name was Franklin Delano Roosevelt, then governor of New York. If the inattentive English major had been approached and asked to comment on the likelihood of the governor one day becoming president, he would probably have had no opinion. Politics was not his forte in those days. By the same token, if Loeb had been told that the governor's wife would one day be his own political ally, that he would become publisher of a newspaper in New York state, the point-man in an ideological crusade to free liberals from Communist infiltration, and that he would be singled out as the "organizational genius" of the strongest non-party liberal movement in the history of American progressive politics, he would have laughed out loud. Unlike clairvoyants, Dartmouth graduates can seldom predict their own futures.

One indication of this inability to predict the future is evident in the grandiose expectations of many Dartmouth graduates in the class of 1929. Not one of them foresaw the economic crash that was tapping America on the shoulder. In fact, America seemed to be so prosperous that, as the young men waited impatiently for Roosevelt's commentary to end, they were contemplating their fortunes fortunes that the near future would bring. "We all thought we were going to make a million dollars," Loeb recalls. "It was just a question of whether we were going to make it in the first year or in the second year."

It didn't come the first year, or the second, or the third. By 1935, Loeb still didn't have a million dollars, and, after getting a Ph.D. in French and Spanish in 1936, he "joined the ranks of the unemployed." A year later, he finally landed a job teaching French and Spanish at Townsend Harris, the preparatory school of the City College of New York. He remained there until 1941. In 1941, he quit teaching. Politics was becoming a full-time job.

"One of my first interests when I came to New York," Loeb says now, "was the Spanish Civil War the struggle to save Spanish democracy from the Franco dictatorship." He goes on to tell of the atrocities people in Spain suffered under Franco's regime.

"Most Americans were anti-Franco," Loeb contends, "but a lot of people were just isolationists. They said, Well, that's none of our business." During this time he joined the board of directors of the North American Committee to Aid Spanish Democracy. Its aim was to raise money in America for the Spanish Loyalists. Soon he began to question the validity of allowing Communists into liberal organizations in America. Liberating Spain was a secondary objective for Communists in the organization, according to Loeb. As a board member, he smelled a rat early in the going.

American Communists were the most creative fund-raisers in the organization. For example, if an event raised $1,000, then $200 went to Spain while $800 went to "overhead expenses." The trick was to have the events in large cities outside of New York. Then the receipts (minus the expenses) were sent to the national office in New York, and when financial reports were sent to the State Department, as required, they did not include fund-raising expenses of the committee across the country.

LOEB lights a cigar and chuckles, recalling how these maneuvers were finally exposed. But American Communists were not the only obstacles to Spanish democracy. The American president was another obstacle. Forty-two years later, Loeb stares out the window of his Norwich, Vermont, home as though hind-sight were a person standing in the driveway by his car, as though he could walk outside and ask the person to change what happened. Then he slowly turns his attention back to the living room and discusses his disappointment in a man he had admired: FDR.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Loeb believes, had the power to save Spain from 36 years of dictatorship. Why wasn't the power used?

"Roosevelt was afraid of the Catholic vote in America," Loeb says with a sigh. He places the cigar in the ashtray, and stretches his long legs in front of him, then hesitates before he speaks again, choosing his words carefully. "The Catholics in America saw it as a battle between Catholics and Communists." Loeb and his colleagues "saw it as a battle between democracy and dictatorship."

The American Catholic Church had more influence within the Democratic Party than all of Loeb's constituents combined. And Roosevelt, although on record as being sympathetic to the Loyalists, "was very much interested in getting reelected." The president, says Loeb, "put an embargo on the sale of arms, ammunition, and assistance to either side. We tried desperately to change his opinion, but Roosevelt stood pat."

As the war went on, the claim here that the Loyalists were Communists became a self-fulfilling prophecy. Loeb had flown to Spain to meet with the Loyalist prime minister and found him to be a left-wing socialist but not an unreasonable extremist; but the rank-and-file members of the Republic were, in fact, becoming more and more extreme in their leftward leanings. Russia was the only side supplying them with arms. Franco, on the other hand, received arms, troops, and planes from both Hitler and Mussolini.

Loeb calls the political polarization of Spanish Loyalists "continued causation." In short, "France gave the Loyalists aid, then withdrew. Britain embargoed them also. The tougher our embargo became, the more the Loyalists were dependent on aid from somewhere else." The longer that "somewhere else" was the Soviet Union, the more to the left the Loyalists leaned. "It was a classic case of continued causation," he repeats.

Sunlight suffuses the cigar smoke billowing into clouds around Loeb's face. German planes bombed civilian homes in Madrid during the final days of the Civil War, killing thousands of noncombatants. Maybe, had Roosevelt lifted the embargo, this tragic bloodshed could have been prevented. Loeb seems lost in thought and speculation. Finally, he extinguishes his cigar and continues: "I was young then, and I hate to pontificate from years later, but my own feeling was that, well, we wanted to break the blockade in any way we could. It's fair to say things have changed over the years. The Catholic influence on the Democratic Party was stronger then than it is now. I was a Roosevelt man, I must say; however, I'm pretty embittered by all that. But, after all, American politics is American politics."

With another cigar in his mouth, a match at the ready, and the melancholy gone from his voice, he says: "So, in the midst of all this, Reinhold Niebuhr, the great liberal theologian, asked me if I'd be national secretary of the newly formed U.D.A."

THE Union for Democratic Action was one of the first national liberal-labor coalitions which, unlike Communistdominated organizations, favored American intervention against the rise of Nazi expansionism. Many labor leaders would have nothing to do with the U.D.A. According to Loeb, the Stalin-Hitler pact of 1939 and the Communist slant of many unions had much to do with this attitude. Loeb talks of Mike Quill, the head of New York's Transport Workers Union. "He had a wonderful Irish brogue that he could turn on or off at will." An Irish brogue wasn't the only thing Quill could turn on or off at will.

On June 22, 1941, just five weeks after the formation of the U.D.A., Quill was giving. a fire-and-brimstone speech denouncing the war against Nazi Germany as an imperialist war. "He said we shouldn't have anything to do with it," Loeb recalls. "Halfway through his speech somebody came up and gave him a slip of paper. What the slip of paper said was that the Nazis were invading the Soviet Union. Quill changed his line right in the middle of his speech. He ended by saying that we should band together for democracy to fight the fascist invaders." Finally, Communists were marching to the same drummer as the U.D.A. It didn't matter Loeb and company were determined to keep them out of the organization.

ANNA, Loeb's wife, hurries into the living room to remind us that in a few minutes Douglas Fraser, head of the United Auto Workers, will be on television. She offers Jim coffee in lieu of his next cigar. He takes a sip, sets the cup down, and lights up again. Anna Loeb is a 1932 graduate of Vassar College who worked with the German underground and later was chief fund-raiser, under Thurgood Marshall, for the N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense Fund. She reminds us that the importance of this telecast is that Fraser will explain why the U.S. government should limit Japanese imports by at least 400,000 vehicles, and how such a decision affects the employment of domestic auto workers.

Loeb was a close friend of Walter Reuther, who rose to the leadership of the U.A.W. in the thirties and took a strong stand against Communist infiltration of the unions. "He won the .battle to put the U.A.W. under non-Communist control," Loeb says, beaming. "I introduced him to Mrs. Roosevelt and he explained the problem [of Communist infiltration] to her." According to Loeb, Eleanor Roosevelt was "a bit naive." After speaking with Reuther, she summoned eight people who were close to her politically and explained why she could no longer be associated with Communists and their fellow-travelers. As the First Lady she could not afford such associations. They all said they were not Communists nor had they ever been. She took them at their word. Later it was discovered that seven of them had lied.

Why was the U.D.A. so adamant in its anti-Communist stance? Were they really such a great threat? "They tended to take control or to try to take control of every organization they entered," Loeb asserts. "Just look at the Aid-to-Spain Committee; just look at some labor unions at that time. Their loyalties were to the Soviet Union" not to furthering the cause of American progressivism. He adds quickly, "There's no question that Communist influence is considerably less today than it was then. But it is still an issue to a certain extent." .

Anna motions for us to be quiet. Fraser is making an important point. The U.A.W. chief says that if the Japanese are so willing to export Toyotas to the U.S., then they should be willing to export factories, also. The Loebs agree.

THE most significant action Loeb took as U.D.A. national secretary was to create pockets of confrontation throughout the United States. The effect in the long run would provide sound evidence that a more politically forceful organization was needed to promote progressive political action.

At the request of the editors of the NewRepublic, Loeb launched a "full-throated" debate by stating that liberals should not "work within the same political organizations with Communists ... if the American progressive movement is to survive and grow." Loeb concluded by challenging progressives to respond to him, for "unless these problems are solved in a period when the presence of Franklin D. Roosevelt no longer lends its unifying strength [Harry Truman was then president], American liberals will sputter, fume, protest, but will get nowhere fast." Proofs of his letter were sent in advance of publication to several well-known liberal leaders with conflicting views. They were asked to comment, and in the weeks that followed no less than ten of them responded.

In the cross-fire of this debate the U.D.A. was transformed. Loeb and other U.D.A. leaders had already convinced Senator George Norris of Nebraska to help expand their organization into a national force back in 1943. The group was now in financial straits. It needed a critical mass of supporters to go on living a critical mass dedicated to the new liberal ideology Loeb had set forth in the NewRepublic. Loeb authorized the concentration of all the U.D.A.'s meager resources on a "final expansion effort."

He had known Eleanor Roosevelt since the Aid-to-Spain days. In early January 1947, at Loeb's request, she came to Washington, D.C., and, in a small conference room of the Willard Hotel, she convinced the conferees to join her, Niebuhr, Loeb, radio commentator Elmer Davis, and several hundred other liberal-Americans to form the Americans for Democratic Action. Mrs. Roosevelt was also instrumental in helping Loeb persuade Philip Murray, head of the C.I.0., to give his blessings to the expanded organization. This was important to move labor to new moorings.

The two most important, and probably most dramatic, tests of A.D.A. power came in 1948, a year after its formation. They included nipping the third party of Henry Wallace in the bud and forcing a civil-rights plank into the Democratic platform when Truman was nominated for reelection. The battle against Henry Wallace was no less than the battle for liberal supremacy.

In 1948, Henry Wallace ran for president on the Progressive Party ticket. It was the kind of Communist "front" party against which Loeb had warned liberals two years before in the New Republic. The make-up of the party was confirmed by Murray of the C.I.O. and none other than Mike Quill, who had defected from the Communists shortly after Hitler invaded the Soviet Union. The A.D.A. accused Wallace of "fronting a movement which could injure perhaps irretrievably the very liberalism for which Franklin D. Roosevelt fought." In addition, claimed the A.D.A., the third party owed "its origin and principal organizational support to the Communist Party of America."

Despite these accusations, the press predicted Henry Wallace would get ten million votes. Not enough to win but just enough to insure a Truman defeat. Jim Loeb made a beeline for the enemy's camp. Thanks to the intervention of friendly reporters, he was able to address the platform committee and most of the delegates.

From behind the podium Loeb began by subtly hinting at the Progressive Party's lack of ideological independence. Once the delegates' attention was riveted he shot from the hip with blistering accuracy: "We [the A.D.A.] challenge the new party to renounce its double standard of political morality, to make clear that it opposes the police state and totalitarian dictatorship everywhere in the world whether in Mississippi or in the Soviet Union. . . . We anticipate, however, that the new party once again will demonstrate that it is an instrument of the Soviet Union. . . . Your movement is a dangerous adventure undertaken by cynical men in whose hands Henry Wallace has placed his political fortunes. It is our conviction that, were the Communists to withdraw from your party today, your organization would soon join that long list of discarded groups testify eloquently to the inevitable failure of the so-called 'united front' which always becomes decreasingly united and increasingly 'front.' "

Angry consternation boomed like a thundercap in the convention hall. The delegates became a mob. Four policemen had to usher Loeb through the hostile crowd and out of the auditorium. Though the Wallace men tried to dismiss the speech, it hit the front pages of newspapers all over the country. As a result, would be Wallace supporters held back their support and many party members dropped out. When Truman beat Dewey later in the same year, Wallace received less than two million votes eight million less than the press had predicted.

The other test of A.D.A. strength came in the battle for civil rights. President Truman, believing that he needed the support of Senators James Eastland and Strom Thurmond, as well as the delegates from Mississippi, was reluctant to put a strong civil-rights plank in the platform. Liberals thought that Truman had sold them down the river because of the conser- vatism he exhibited during his first term in office: In short, the New Deal was being co-opted under Truman.

Loeb and the A.D.A. had waited for a strong civil-rights plank since Roosevelt's death, and they weren't going to wait any longer. Besides, the Democrats owed the A.D.A. a favor for all but destroying the Henry Wallace party earlier in the same year.

There were four A.D.A. men on the platform committee out of more than 100. One of them was Hubert H. Humphrey, mayor of Minneapolis. Loeb calls Humphrey "my best friend in politics." Now they were in cahoots against the hand that fed them: the party itself. This, however, didn't seem to disturb them. Like a posse with a warrant, they served notice on the entire delegation: "The New Deal is unfinished business," they stated, because "the problem of discrimination has not been dealt with." While Loeb and A.D.A. delegates led by Joseph L. Rauh were trying to sway various delegates in all-night sessions, Humphrey prepared his speech on the A.D.A. position to be presented to the full platform committee. The committee rejected the plank with a "substantial voice vote." So they took it to the convention and fought it out on the floor.

The air in the convention hall reeked with barely pent-up violence. No blows were exchanged, but if threats could kill there would have been several A.D.A. casualties. Northerners accused the A.D.A. of trying to split the party on a pet issue. Thurmond and Eastland smoldered; later in the convention they would leave and form their own party.

A tumult of booing and fist-shaking erupted when George L. Vaughn, a black Missouri delegate, spoke to the convention and called for the immediate unseating of the Mississippi delegation for its failure to support the civil-rights plank. When Humphrey spoke, however, the mood of many delegates began to change. In fact, he was repeatedly interrupted by prolonged applause from various Northern delegations. "To those who say we are rushing this issue of civil rights," Humphrey challenged, "I say to them, we are 172 years too late. To those who say that this civil-rights program is an infringement of States' rights, I say this, that the time has arrived in America for the Democratic Party to get out of the shadow of States' rights and walk forthrightly into the sunshine of human rights."

Northern delegates gave him a standing ovation. The Southern delegates were more angry and demonstrative than Henry Wallace's Progressive Party. After Humphrey had finished, Loeb walked side by side with him down the aisle of the convention hall. By then, Loeb says, the hatred was so vociferous and unabashed that "I didn't think we were going to make it out of there alive. The place was an absolute bedlam. I swear to God, I thought we were going to be shot." In spite of it all, the A.D.A. resolution passed 651 1/2 to 581 1/2. The Southern delegations stormed out of the convention hall, and Strom Thurmond suffered a defeat the likes of Henry Wallace's in the general election.

TODAY, Loeb sees the platform fight for civil rights as something that could never have taken place in the Republican Party. Not in 1948, anyway. He claims the Republicans' lack of initiative on the issue "has been one of their weaknesses." "The A.D.A. brought the issue of civil rights to the foreground of American politics. There's no question about that! Any liberalism that doesn't include civil rights is ill-liberal. But liberalism isn't just for the civil rights of black people, it includes all sorts of other people, too."

Loeb calls the current period of American political history a "very grave moment." He worries about the future of "any form of liberalism" during the Reagan Administration. "This is the most conservative not to say reactionary administration that has existed during my active career." Southern Democrats as well as Northerners "are switching over to the Republican Party in significant numbers," he says. "Eugene McCarthy's move to support Reagan is impossible to figure out. I just don't understand it. It strengthens the feeling that he was a strange sort of fellow."

"Wholesale cuts in the budget are going to affect blacks more than any other group. I'm not an expert, but I think you have to balance the thing, and I don't think it's being balanced." When Loeb calls for "balance" he's not only speaking of the budget itself, he's speaking of balance in the number and kind of programs that are cut in order to achieve a balanced budget. "We're cutting social programs and increasing military ones," he explains. "In the long run we will weaken as a country." As an organization, A.D.A. grew steadily after the 1948 Democratic convention. Loeb remained national secretary until 1952. Though the organization was to be non-partisan and support candidates at the local, state, and national level who were liberal, regardless of party affiliation, it became a strong arm within the Democratic Party. By 1962, it was so influential, so noted for bringing out the vote that John Kennedy named three A.D.A. veterans to his cabinet, three as White House aides, 31 as key administrative advisers. He was apparently so pleased with Loeb that he appointed him ambassador to Peru in 1961 and ambassador to Guinea in 1963. Loeb took time off from his work at the Enterprise, a newspaper he and a partner owned in Saranac Lake, New York, to fill these posts, then finally sold the paper in 1970. By then his two children were grown up and married, and Loeb was looking around for a place to retire.

He found that place just across the river from where he and his classmates dreamed of making a million dollars while Franklin D. Roosevelt gave the commencement address in 1929. As he often says, "I came to Dartmouth and I loved it."

Since the late seventies he and Anna have been attending lectures and auditing classes alongside students. She was an economics major at Vassar; he was an English major. She audits few economics courses, however, and he audits few if any English courses. They are most familiar to government professors. Politics has been their calling.

True, this may be "a very grave moment for the future of any form of liberalism," but Loe and other liberals persevered with patience through the Eisenhower years. Then, all of a sudden, everything was golden when they elected Kennedy. The Jim Loebs of today will have to exhibit the same kind of patience until another golden boy of the Democratic persuasion comes along. Who might he be?

"I would vote for Fritz Mondale for anything!" Loeb exclaims. But the Minnesota Democratic Party, Mondale's base of support, is in "bad shape." It lost to Republicans in the last congressional race. Also, Mondale's future aspirations may be hurt by his association with Jimmy Carter. The ashtray by Loeb's elbow is filled to capacity with cigar butts and ashes. He reaches for the cigar box before dissecting the Carter administration.

Loeb has always been a good Democrat and voted along party lines. He even voted for Carter last November because he honestly believed in Carter's policies over Reagan's. "Carter was not up to the job," he admits now. "I've always had the theory that in 1976 Carter benefited enormously from the Nixon fiasco."

According to Loeb, the biggest mistake Carter made came during the first few months of his term in office. "From the very beginning he gave absolute assurance he would never call for wage and price controls. He was beaten then. I'm against controls, but there comes a time in a bad economy when you have to have controls. And if things get bad enough you certainly have to have them as a threat to the manufacturers and oil producers even if you don't intend to use them. Look what's happening now: Profits are soaring in some fields, yet who are the victims of these enormous tax and budget cuts we're making? Blacks and the poor. Again, basically I'm against wage and price controls unless they're absolutely essential. But they're essential!"

Mondale's ability "to shake the negative association" of having been Carter's vice president will have a lot to do with his own run for the presidency, says Loeb. "That's the thing that killed Hubert the vice presidency. Some of us pleaded with Hubert not to accept the vice presidency, especially under Johnson, who was so domineering."

Mondale's image, Loeb realizes, is not the only thing standing between him and the presidency. Reagan could have something to do with it, also. "The two question marks," Loeb postulates, "are 1) is Reagan's foreign policy going to change [become less hawkish] and 2) are all of these cuts that affect the poor going to have any major repercussions." If the answer to the first question is yes and the answer to the second question is no, then, says Loeb, Reagan will be reelected.

The admiration for Mondale goes back to the early fifties when he came to the A.D.A. office in Washington. Loeb says he "gave Fritz his first job out of college," organizing students for the A.D.A. "His personality is very appealing," Loeb says. "He has a wife who should be a great asset. He's extremely intelligent, and he's not an extremist. He's solidly liberal, but he's no screwball. He's got his feet on the ground. Finally, he speaks well."

BUT the big issues of today are not the big issues of 1948, as Loeb well realizes. Time seems to move faster, and the line drawn between liberal and conservative is more complex, the gray area widening with each passing day. Still, if it had not been for James I. Loeb, liberal ideologues would stand on foundations even more unstable than today's. He forced liberals to "make several basic decisions regarding their own policies and convictions." One was the adoption of civil rights as a liberal cause. The other came from his doctrine on how to be left-of-center yet non-Communist. Some have called the latter point too didactic, too hard-line for members of progressive movements. Nonetheless, it was crucial to the shaping of today's liberal-labor organizations.

LOEB extinguishes his last cigar, stands, and stretches. As a parting shot on Reagan's policies, he remarks, "FDR would have done it differently." The ashtray beside his chair is a gift from an old friend in politics. In the bowl of the ashtray, under the ashes and the six or seven butts, is the picture of a small beagle, and the words by the beagle read, "A man's best friend is his dogma."

Talking to friendly and hostile audiences,Loeb stirred up "pockets of confrontation."

Loeb greets a beaming Hubert Humphrey,who was later hurt by the vice presidency.

A government major, Frank Wilderson '78graduated at the end of the winter term. Hefirst met James Loeb when they audited agovernment course together four yearsago.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue