WHEN an engineer with a grant to study Incan construction techniques in the Peruvian highlands asked Chauncey Loomis to tag along and take pictures, Loomis probably didn't realize that his response would lead to a lifetime of travel around the world, a book about a 19th-century Arctic explorer, and more than a few good drinking stories. But then English professors don't usually make claims of prescience, even at Dartmouth.`

At the time, Loomis was teaching at the University of Vermont, exhibiting photographs semiprofessionally, and working on his `dissertation about Thackeray. The proposition appealed, so Loomis read up on the Incas, went on the study he still recalls the sense of luxury they felt at having Machu Picchu to themselves at night - and mounted an exhibit of the photographs on his return. John J. Teal Jr. '42, an anthropologist and explorer, saw Loomis' work and invited him to join several trips north. Loomis soon found himself very much interested in the exploration, and the history of the exploration, of the Arctic. Among his considerations in coming to Dartmouth in 1961 was the College's acquisition of the Arctic literature collection of Vilhjalmur Stefansson, one of the region's great explorers.

It was in the Stefansson Collection that Loomis happened upon the life story of Charles Francis Hall, an eccentric printer who lived in the mid-19th century. Hall, given to exclamations of wonder about the glories of nature and technology, came to believe that he had been divinely selected to discover the North Pole, then the object of intense international fascination. In July 1871, Hall, in command of a converted Navy vessel, set out for the Pole and succeeded in reaching the most northerly point that had yet been recorded. Just five months later, however, he mysteriously died while waiting for the ice to break up and free his ship. Loomis, in the course of researching Weird and Tragic Shores, his book on Hall's life, discovered that Hall's death had never been conclusively explained, and so, in 1968, he organized a visit to the site of Hall's grave in northern-most Greenland. The body was exhumed, and when samples taken from the remains were later analyzed, they were shown to contain an unusually high level of arsenic. It was at least probable, Loomis conjectures, that Hall's crew did not appreciate the captain's fanaticism or his imperiousness. periousness

The scholarly prodigiousness of Loomis' detective work tends to overshadow the exploratory achievements. As part of the Hall research, however, Loomis made several Arctic journeys, including one summer spent traveling in an Eskimo seal boat. "That was the only way I could see certain areas that Hall had been in," he says of a trip on which he shared his companions' meals of seal blood as well as Campbell beans. "Drinking blood is not my idea of heaven, but I must admit that the seal liver was absolutely delicious we cooked it."

Loomis, admittedly, is not a believer in adventure or daredeviltry for their own sakes. Exploration must combine both physical and intellectual delight to be satisfying, Loomis argues, and a dangerous exploit should be undertaken only when necessary. "Those who are out there just to wear woolen shirts and show that they can saw wood are jerks. I distrust someone who says that if you climb a mountain you're a finer person. That's absolute nonsense. A while back, there were posters all over campus saying, "Need a challenge? Go Outward Bound. 'I still remember Jim Epperson bless his dear soul wheeling on a class one day and saying, "You need a challenge? Read the fourth book of TheFaerie Queene. And he was right. Reading can be as much of an adventure as anything."

We tend to romanticize exploration, he maintains, even though most great explorers have been technicians. Any of the, engineers at the Cold Regions Laboratory in Hanover have had more adventure than he has, says Loomis; they just don't recognize it as such a mixed blessing. He recalls that Stefansson once said, "I hate the very word adventure, it means that something's gone wrong.' "

Not that Loomis has always heeded Stefansson's wisdom so faithfully, at least insofar as fun and adventure intertwine. Before the African safaris and a more recent trek in Sikkim which, notes a chagrined Loomis, reminded him of his age was a trip to Nunivak Island, off Alaska, with John Teal. Teal had already made a reputation for himself by capturing musk oxen and trying to domesticate them for their wool. Loomis went along on this later trip with a movie camera, the result of which was aired on a CBS special, "Wild River, Wild Beasts."

"The trouble with capturing musk oxen is that you've got to separate the calves from the adults. When they'd done it before, they'd always just killed the adults. Of course, that would be frowned upon nowadays. Teal discovered the system of driving them with an airplane, herding them towards water. Once you get them on the edge of a lake, you sit around (and we sat around for hours) beating drums, yelling, screaming really it's outrageous what you do until finally they get so annoyed that they go into the water. Once they get into the water they break up, and at that point you can separate the calves."

Peter Matthiessen, the distinguished writer and a good friend of Loomis', accompanied Loomis and Teal on several trips. "His evocation of what a musk ox looks like is really good. And very simple. He's just picked those salient characteristics which, if you or I were looking at them, we wouldn't see, or we'd be seeing them but we wouldn't know we were seeing them," relates Loomis. "Matthiessen's prose is very crafted because he works so diligently at it." Loomis recalls a time on a caribou trip when Matthiessen spent the whole day working on a page and a half in his journal, a page and a half that was later rewritten for a New Yorker article.

Loomis takes a professional interest in the process of transforming experience into recollection into the written word. Explorers, he points out, tend to rationalize and distort their experiences as soon as they put pen to paper, whether it be 30 seconds or many years after the original event. "Explorers' journals can be fascinating that way. You try to reconstruct what actually happened and locate the rationalizing, the kinds of inner guidance that are operating as a person recalls an experience. Is he writing what actually happened or what he thinks happened or what he hoped would happen? Nine times out of ten, somebody who keeps a journal is writing what he thinks should be in that journal. But I think Matthiessen has Hemingway's attitude: get at 'what I really saw, not what I was supposed to see and what I had been taught to see but what I really saw and felt.' "

Hemingway's "innocent eye" is not the only thing about the author that fascinates Loomis, who contends that Papa himself didn't take the macho image and the "Hemingway code" totally seriously. The machismo was a pose Hemingway adopted in response to his self-consciousness and to feed his "monstrous" ego, says Loomis. Of course, the pose sometimes went too far. Hemingway's hunting guide, Denis Zaphiro, whom Loomis met on a trip to East Africa, related (after getting a bit drunk) the story of a trip on which Hemingway's plane crashed twice. "Hemingway was in Uganda," Loomis recalls, "and he and his wife Mary decided to fly around and look at the falls. Apparemtly they both got macho she used to compete with him and they kept telling the pilot to fly lower. He did and caught a wire that was stretched across a gorge and they crashed. They were damn lucky that nobody was killed. Hemingway was not too badly injured, and when they got him to another plane to go to Nairobi, that plane crashed on take-off and burst into flames. Mary and the pilot were able to get out, but Ernest was stuck in the back while the plane was burning around him. They could hear him roaring in there like a bull. He was pounding on the fuselage. Finally he broke out and was not too badly burned. But he was burned. So there he was on the pavement and Mary, his loving wife, looked at him and said, 'What's the matter, Papa, scared of fire?'

"After that, his burns were bad enough so that he had to rest up, at Mombasa. While they were there a bush fire started up. Denis and all the men working for him and Mary went out to fight it. Ernest was in bed, but when they finally put out the fire and went back to the house, they couldn't find Hemingway. They finally found him he had been in the middle of the fire, fighting it on his own, and was really quite badly burned. Denis shared a room with him for a couple of nights because the injuries were very painful. And at one point, Denis told me, Hemingway looked up at him and said, 'That'll show her.'"

Loomis' current project, a book, will contrast three explorers and their varying conceptions of space: the undefined space of Henry Hudson, the linear space of John Ledyard, and the enclosed space of an East African border official (whose writings Loomis acquired in the sixties). Loomis, who has been in all sorts of space, prefers "the big-sky stuff. Isak Dinesen, one of the great writers about East Africa, said the sky burns, and it's that simple. Oddly enough, you get the same thing in the Arctic, that vast, intense sky and a sense of openness." One sort of space that Loomis has yet to experience is outer, though he used to fly an airplane. He says of the space shuttle, "I love it. It's gorgeous right out of a dream to see that thing come up out of the smoke and dust. Pssshhhhoooo. Boy, would I love to get on that thing."

Loomis sounds undaunted, despite his characterization of rough travel as "hours and hours and days and even weeks of discomfort, and sometimes a little bit of fear." Because, he says, "what you get in return is maybe two minutes of absolutely exquisite beauty. And it's worth the whole thing."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTelling Another's Tale

May 1981 By Gregory Rabassa -

Feature

FeatureThe Last of the Liberals?

May 1981 By Frank B. Wilderson -

Feature

FeatureOnce King and Future President

May 1981 By David Shribman -

Article

ArticleGreat Issues, Etc.

May 1981 -

Sports

SportsThe Club Set

May 1981 By Brad Hills '65 -

Article

ArticleCampaigning

May 1981

Don Rosenthal '81

-

Article

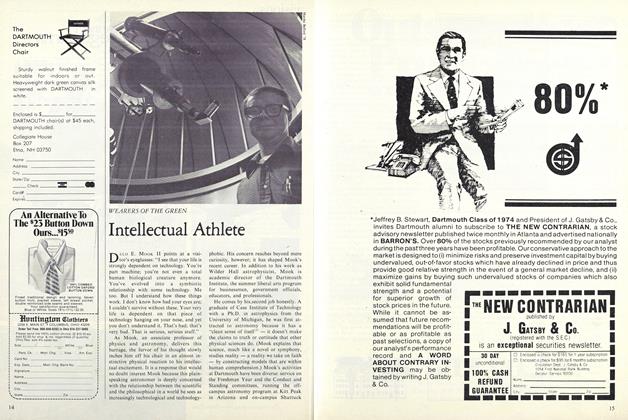

ArticleIntellectual Athlete

October 1980 By Don Rosenthal '81 -

Article

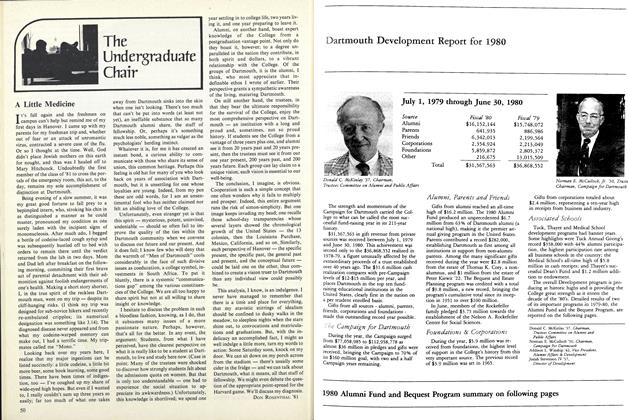

ArticleA Little Medicine

October 1980 By Don Rosenthal '81 -

Article

ArticleBeware the Shrimp

Jan/Feb 1981 By Don Rosenthal '81 -

Article

ArticleImagining Beyond Limits

March 1981 By Don Rosenthal '81 -

Article

ArticleWhere They Live

April 1981 By Don Rosenthal '81 -

Article

ArticleA Straight Talk

June 1981 By Don Rosenthal '81

Article

-

Article

ArticleRESIGNATION OF SECRETARY TOWLER

April 1918 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Enroll 86 Sons in This Year's Freshman Class

November 1938 -

Article

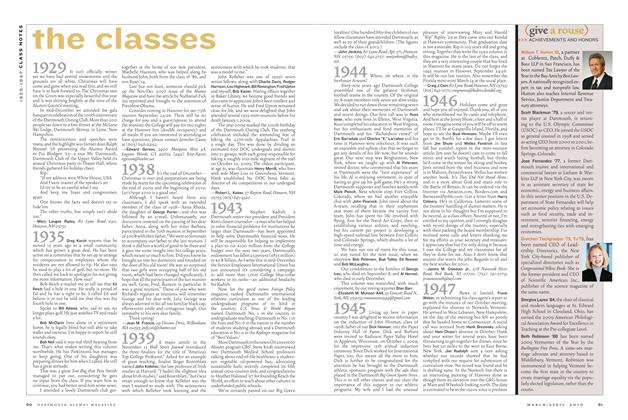

ArticleClass of 2013

OCTOBER 1996 -

Article

ArticleGive a Rouse

Mar/Apr 2010 -

Article

ArticleA Visit to Hanover

June 1929 By E.W.Field -

Article

ArticleMedical School

OCTOBER 1965 By HARRY SAVAGE M'27