WAYWARD REPORTER: The Life of A. J. Liebling by Raymond Sokolov Harper & Row, 1980. 354 pp. $16.95

In 1920, a 16-year-old Dartmouth freshman named Abbott Joseph Liebling from Far Rockaway, New York, was impressed by Hanover's biting cold, the "wonderful" football rush, the "exemplary freedom of thought and speech," and compulsory chapel where the whole college sang "Onward Christian Soldiers." "His only complaint at Dartmouth was with the menu, which relied heavily on beans." He threw himself into his studies and writing, heeled for Jack O', and continued his life-long interest in boxing. His roommate was kicked out for bootlegging, and in 1922 Liebling was permanently expelled for too many chapel cuts.

Journalist and food critic Raymond Sokolov tells us that A. J. Liebling was to become "perhaps the greatest reporter of his time," "the most important boxing writer in a century," the inventor of modern press criticism, literary descendent of Hazlitt, Dickens, Stendhal, Cobbett, and Borrow, precursor of the so-called New Journalism, and an aweinspiring trencherman.

Sokolov's prim introduction of his subject seems at first unlikely to explain how this gourmand of life and chronicler of low-lived odysseys could have become any of these things. But Sokolov's knowledge of food, France, 0and the writer's trade comes to the rescue as he warms to his subject. He can distinguish a sauce choron from a simple bernaise, he knows what the view would be from a hotel window in Avranches, and he can illustrate with striking examples Liebling's technique of "mosaic accumulation" and his "search for authenticity in squalor and for humbled but persistent seriousness of craft."

"From 1936 to 1939 Liebling put his New York on paper in The New Yorker ... an album of lovable undesirables ... the real denizens of the city's modern Bartholomew Fair." As a war correspondent, Liebling, by concentrating his attention on mundane and undramatic detail, "compressed the drama of D-day to a few feet of deck." After the war and for the rest of his life, Liebling wrote as the conscience of the press, railing against publishers, lampooning cliches, ferreting out blunders, and denouncing injustice. The culmination of his more self-conscious reporting, NormandyRevisited, which Sokolov calls Liebling's 'masterpiece," appeared in 1958. But it is his uncanny coverage of boxing on the model of the 19th-century writer Pierce Egan that most NewYorker readers of the 1950s now remember.

Sokolov does a reasonable if not exhaustive job of defining Liebling's armchair political liberalism, which he rightly likens to the social consciousness of Mark Twain. He takes on, successfully I think, those critics who insist on something sinister in Liebling's friendship from 1947 on with Alger Hiss, although Sokolov leaves unexamined the possible parallel between Hiss and the confidence men who so fascinated Liebling the novelist manque. Sokolov is also deft and considerate in his account of Liebling's true and moving loves with wives Ann, Lucille, and Jean as well as his seemingly devil-may-care skirt-chasing.

One suspects that this compulsive whale of a man might have been a little hard to take at times, but those who knew him say no. Liebling's sometimes dyspeptic eccentricity and apparently suicidal intake of food and drink notwithstanding, Sokolov leaves the reader despairing that Liebling's talent was cut off by pneumonia in 1963, too soon to take the journalistic measure of the cons and outrages of the succeeding decade. Sokolov also makes the reader believe that our great-grandchildren will read Liebling on his time and place in verification of his "tacit claim to be a writer of lasting significance who worked within the confines of factual reportage."

Peter Grenquist is a book publisher in NewYork.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTelling Another's Tale

May 1981 By Gregory Rabassa -

Feature

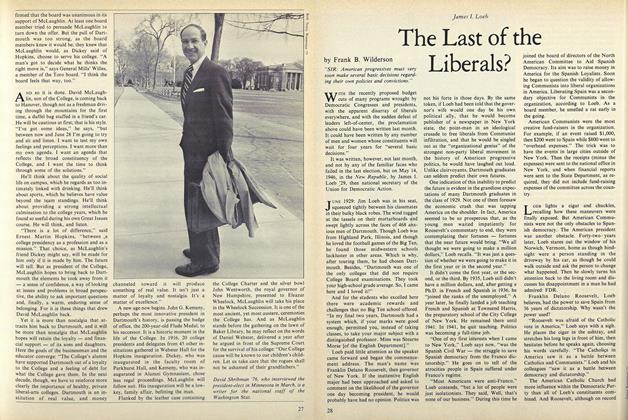

FeatureThe Last of the Liberals?

May 1981 By Frank B. Wilderson -

Feature

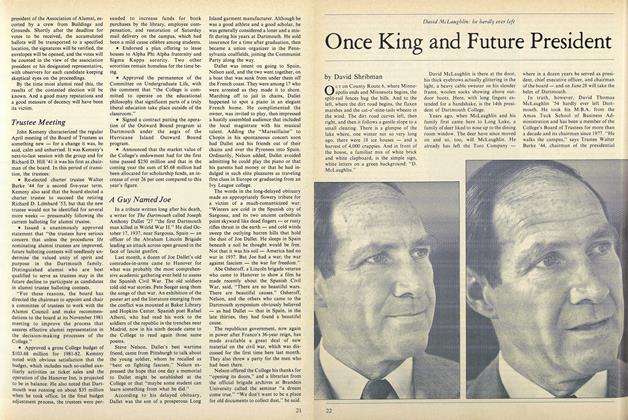

FeatureOnce King and Future President

May 1981 By David Shribman -

Article

ArticleMind for Adventure

May 1981 By Don Rosenthal '81 -

Article

ArticleGreat Issues, Etc.

May 1981 -

Sports

SportsThe Club Set

May 1981 By Brad Hills '65

Peter C. Grenquist '53

Books

-

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

May, 1923 -

Books

BooksMr. Willard T. McLaughlin '25

November 1932 -

Books

BooksTHE CASE FOR EXPERIENCE RATING IN UNEMPLOYMENT COMPENSATION AND A PROPOSED METHOD

May 1939 -

Books

BooksFaculty Book

NOVEMBER 1970 By JOHN HUKD '21 -

Books

BooksBriefly Noted

MARCH 1971 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksHELIX,

October 1947 By Sidney Cox