Here is an opportunity to test your knowledge ofhistory: How many of these and the following notablepeople can you identify? Can you describe accuratelytheir contributions to society? Hints are provided tospeed you on your way, and the answers appear right side up at the end.

Why study women? This seems an appropriate question to ask on the tenth anniversary of coeducation at Dartmouth. The great coeducation debates of a decade ago seem today like so much ancient history. There is no longer a coeducation question at Dartmouth. There is not even a coeducation controversy or a coeducation issue. There is coeducation. The changes since 1972 are nothing short of remarkable. Women once were allowed to comprise only a small fraction of the student body; this year, women make up 43 per cent of the freshman class, and with males no longer given an edge in admissions, the 50:50 mark may well be reached before another decade is out. There are sororities on campus, there are occasional women's events, there's an ever more impressive women's athletics program, there is bathroom graffiti the likes of which would never have appeared ten years ago, and there is in the walk of many of the undergraduate women an assurance that bespeaks a sense of viscerally felt belonging not known to the many women who blazed the paths ten years before. Problems still exist, of course, but women now seem accepted at Dartmouth. Those who lived through the transition years may recall the changes as painfully slow and disruptive, but seen in terms of the life of the institution, they occurred relatively quickly and relatively smoothly.

Yet for all the progress Dartmouth has made in integrating women in the past ten years, there remains in the College community an undercurrent of old-school sen timent. One of the ways it manifests itself is in a suspiciousness toward the idea of women's studies. While no one or hardly anyone in the Dartmouth community today would seriously ask why educate women, many would still ask why study women. Women may have been accepted as students, but as subjects of serious scholarship no way, not yet. Indeed, as I write this I can hear the sighs of exasperated readers who can't understand why a magazine would publish an essay on so bogus a topic. I can also hear the words of a tenured Dartmouth professor who asked me a few years ago, "What are you writing about other than women, that is?" The word women was uttered with such a hiss of condescension that the professor's message was unmistakable: Women are trivial, inconsequential, beside the point.

Yet it's not merely to counter the curmudgeonly opinions of some among us that I raise the question why study women. I raise it because it, in turn, raises fundamental questions about the concept, purposes, and content of a liberal arts education. I raise the question, in short, because when you ask, "Why study women?" ultimately you ask what a place like Dartmouth is really all about.

Why study women? In considering this question, it helps to recall Pope's comment that "the proper study of mankind is man." Then it helps to realize that since the advent of formal learning in the West, what Pope articulated scholars have been acting on. The end result is that through every academic discipline runs an androcentric bias that effectively eliminates the experiences, contributions, and perceptions of more than half the human race. This androcentric bias has skewed and constricted the thinking of educated persons for thousands of years and reveals as a sham the sacrosanct notion of scholarly objectivity. Yet until recently this bias was so accepted that few noticed it, much less criticized it.

Given the historical context in which our academic traditions have their roots, the androcentricity of academia seems inevitable. Misogyny had long been in full flower by the time men first established centers of formal learning; hence a basic premise of the academy was that education was for men and only men. The exclusion of women meant that men posed all the questions and provided all the answers; and eventually it came to pass that every area of academic inquiry had men and men's concerns at its center. Men recorded their experiences and called it history; men looked about the world and called their observations science; men wondered about the existence of God and the problem of evil and called their speculations theology; men did handiwork and called it art; and men thought about topics such as truth, beauty, and the nature of existence and called their opinions philosophy. Not coincidentally, many of the basic "truths men discovered served to keep men at the center of attention. Among these are such "truths" as "Man was created in God's image," "Man is unique among the animals," and "Man is the measure of all things..' Laugh as we now may at the naked narcissism of such "truths," the sentiment behind them still shapes considerably the direction of academic enterprise.

Although the student population in this country would be predominantly male until the 19705, women in America began to gain access to institutions of higher learning in the mid-19th century, and by 1920 nearly a quarter of a million women were enrolled in American colleges and universities. In a situation much like the one at Dartmouth today, women's entrance into the academy did not, however, bring about any of the fundamental changes foes of women's education had predicted. The walls of the buildings did not crumble, the men were not all corrupted, and the women did not collapse under the rigorous mental strain. Moreover, the androcentricity. of what was being taught at institutions of higher learning continued to go unchallenged. Women and men alike did not question why no women writers were included in literature courses, why women appeared in history books only as bit players (if they appeared at all), why women in the physical and social sciences were treated as a deviant subspecies (again if they were mentioned at all), and why it was that going whaling was seen as a topic worthy of writing about at length while giving birth was considered "trivial," "not serious," and unworthy of discussion. Few as well questioned why it was that when occasional questions about women and women's experience did crop up, men were automatically turned to fox the answers. Very simply, it was taken for granted that if you wanted to know what really goes on in women's heads, you went to Freud, and if you wanted the first and last words on female orgasms, you consulted D. H. Lawrence.

A principal reason academic androcentricity has so long gone unchallenged is that most of us were taught that women have from the dawn of time been passive receptors of culture, never its creators. "Of course, scholars haven't troubled with women women have never really done anything!'' Supposedly, this explains why women have been excluded from so many fields, particularly history. In fact, it is a myth that women have never really done anything, a myth that arose as a direct consequence of academic androcentricity. Throughout history, women have accomplished a great deal, and a great deal of note and importance; but the men keeping the official records of the race did not deem their accomplishments worthy of recording. Worse, men have often appropriated women's accomplishments and called them their own. Take the cotton gin, for instance. Contrary to history as men have written it, Eli Whitney did not invent the cotton gin: his landlady, Catherine Green did. However, married women at that time could not legally hold patents, Catherine had to get Eli to obtain the patent, and so he rather than she went down on record as the inventor. (A Saturday Review cartoon shows two cavewomen putting the finishing touches on their latest invention, the wheel. Says one cavewoman to the other, "What really gripes me is that centuries from now men will be getting all the credit for it.")

I want to state quite clearly that in raising the question, "Why study women?" I don't mean to imply that there is anything wrong with studying men. Men are nearly half the human race, and men's experience, contributions, and perceptions are valid and worthy of contemplation and study. Men's experience, however, should not be confused with universal human experience and it is in this respect that I do see something wrong. Bad as it is that scholars for centuries have closed their eyes to the experience of one half the human race, even worse is that in the process they've presented male experience as representative of everybody's experience.

On my desk is a stack of studies pertaining to self-esteem, a subject I've spent several years researching. All sorts of different people are includedin these studies: students, blacks, whites, Protestants, Jews, Catholics, college graduates, high-school graduates, people from various class back grounds. When I first found these studies, I was thrilled; they seemed to have just the information I was looking for. As I began to read, however, it became clear that they would be of no use to me. Why? Because my specific topic of interest is women and self-esteem, and all these studies, while presented as being studies of students, blacks, whites, Protestants, etc., are actually about male students, male blacks, male whites, male Protestants. The men who conducted and wrote these studies saw no need to specify the gender of their subjects. They took it for granted that male students speak for all students, and in this respect they are not alone. The vast majority of social science studies have used only male subjects, and it is from the study of males and males alone that universal conclusions about humans have been drawn.

Also on my desk at the moment is a book called The Birth and Death of Meaning, by Ernest Becker, an esteemed scholar and the winner of a Pultizer Prize. Becker, too, discusses self-esteem, and like so many other authors he uses throughout the book the terms "man," "he," and "the individual," and uses them in such a way as to suggest that he is speaking of some genderless being who represents us all. When he starts discussing "the peculiar symbols" that "the individual" retains in "his mind" in order to maintain "a warm feeling about himself," however, Becker reveals that the ostensibly genderless individual he has in mind is, in fact, very much a male. For these "peculiar symbols," Becker tells us, include not only "the money he made, the picture he directed, the book he published" but also "the girl he seduced." Becker does not once stop to consider what might be going through the mind of this "girl" or how she might have been affected by the seduction. Nowhere does he deal with the contradictions inherent in his imprecise language. He seems dimly aware that male and female experience might be different, but at the same time he speaks of "man" and "the individual" as if these terms were generic. There are two words for this: arrogant and muddled.

Becker's confused and confusing use of the term "man" is not an isolated phenomenon. Libraries like those at Dartmouth contain literally hundreds of thousands of scholarly tomes and papers on topics such as man and democracy, man and madness, man and nature, man's search for meaning, man's search for himself, man among men. Ad infinitum. The man these works speak of supposedly stands for all humans, but the occasional and cursory reference to women in some, and, more tellingly, the examples the authors use generally make it clear that the man being spoken of is really a male man. A white, heterosexual male man, who has a lot in common with the average white male college professor at that.

NOT all scholars see male experience as universal. Yet even where it is conceded that male and female experience may be different, androcentric assumptions interfere, causing the male experience to be looked upon as the norm and the ideal. To many scholars, man is still the measure of all things or at least all things female.

From Aristotle on, the vast majority of the men billed as having Western civilization's best minds have all blithely assumed that the normal and ideal human is the male, and that the female is by comparison deformed, mutilated, castrated, weak, and faulty. Today, this assumption still pervades, so that when tests show males to be more competitive and aggressive than females, the females are automatically judged to be flawed. Too rarely considered is the possibility not that women are insufficiently competitive and aggressive, but that men are too much so even though this is precisely what the heart attack and violent crime rates among males suggest.

Research on moral reasoning well illustrates how the "male as norm" premise can skew scholarly inquiry. In the 19605, Lawrence Kohlberg of Harvard used an allmale sample to study how people make moral decisions, and came up with the theory that humans pass through six sequential stages as they grow toward moral maturity. It just so happened, however, that when females were finally studied, they showed a development pattern that did not jibe with Kohlberg's model. Hence, females were labeled as both abnormal and deficient in moral reasoning ability.

In the 19705, Carol Gilligan, also of Harvard, looked at Kohlberg's work and suggested that maybe the problem wasn't that females don't fit Kohlberg's model, it's that the model doesn't fit them. Scratching the "male as norm" idea, Gilligan set out to study how females make moral decisions, and she discovered that females have methods of moral reasoning that are not only different from male methods but more complex as well. Males, she found, typically see the world as consisting of separate individuals, and when making moral decisions their primary concern is that individual rights be interfered with as little as possible. Females, Gilligan found, typically see the world as one in which individuals are interconnected by a complex web of relationships, and when making moral decisions their primary concern is that the exercise of individual rights not interfere with a presumed basic responsibility to help and protect others. According to the Kohlberg model, the first way of looking at the world is the morally mature way, the second is the morally immature way. Gilligan, however, disputes this. Why, she begs we ask, is it more moral to think principally in terms of the individual than in terms of the community? Is it not precisely this "me-and-my-interestsfirst" thinking, so encouraged among men in our culture, that has created so many of our culture's problems?

To me, one of the most disturbing things about the androcentricity of the typical liberal-arts curriculum is how it has given rise to some very debatable conclusions about both history and humanity. The exlusion of the experiences and roles of women from history in particular reduces by more than half the lessons we can learn from the past and constricts our conception of the human condition as well.

the view of Western history that most people derive from a liberal-arts institution is one that looks upon the democratic period in Greece as the height of civilization, sees the Middle Ages as a time when civilization deteriorated, sees the Renaissance as a time when civilization again progressed, and sees the period following the American revolution, particularly the Jacksonian era, as one of increasing popular liberty. This is the conventional, androcentric view. When Western history is seen from the vantage point of women, the picture that emerges is the complete opposite. For women, democracy in Athens meant either concubinage or, in the case of citizens' wives, perpetual confinement indoors and a protein-deficient diet. For women, the Middle Ages meant increasing freedom and power in many respects, as well as improvements in diet and health. For women, the Renaissance meant loss of freedom and power, the denigration of the kinds of knowledge and methods of learning women had traditionally developed, and the escalating terrorism of witchcraft persecutions. For women, the period following the American Revolution, particularly the Jacksonian age of "the common man," meant fewer legal rights, not more.

As it has limited and distorted our view of history, the androcentricity of conventional accounts of history has also helped to limit and distort our notions of what it means to be human.. The history of the human race as men have written it places heavy emphasis on dominance behavior on warring, killing, conquering, colonizing, ruling, and exploiting as seen from the dominant point of view, and it is from this version of history that people have drawn such universal conclusions as "humans are aggressive by nature" and "humans have always resolved conflict through war and always will." Yet if we looked at the sides of the story those in positions of dominance have chosen to keep out of the standard historical record, we would not so readily accept these commonly accepted assumptions. If, for example, we drew our universal conclusions about humanity exclusively from the female side of the story, we might well conclude that human beings are nuturing, not aggressive, and typically given to resolving conflict through verbal communication and nonviolent conciliation rather than war. And if we did as we should and looked at all sides of the story, we would probably conclude that it's ridiculous to speak about humans being immutably one way or another. If human history teaches us anything, it's that human beings have the capacity for a wide range of behaviors, from committing terrible acts of violence to performing tender acts of love. This is a truth that may be essential to the survival of the human species in our increasingly dangerous age, but sadly it is a truth androcentric history all too easily obscures.

WHY study women? At the outset of this essay I raised this question Because it, in turn, raises fundamental questions about the concept, purposes, and content of a liberai-arts education. I hope by now what I meant by that statement has begun to become clear. When you study women you are forced ultimately to reexamine all you have been taught and to recast in a fresh perspective age-old questions: What is truth? What is morality? What is progress? What is civilization? What does it mean to be human? Moreover, when you study women, you also end up asking the fundamental question Virginia Woolf posed in The Three Gunieas: "Where is it leading us, the procession of educated men?"

There is yet another question you have to confront when you study women: What are worthwhile things to do with one's life? This seems especially pertinent to consider on the tenth anniversary of coeducation at Dartmouth. Dartmouth states as its purpose the education of men and women who have the potential to make a significant contribution to society. Yet what is it that we consider either significant or contributory? Our culture, with its overriding masculine bias, has traditionally defined as significant things that males do and dismissed as insignificant things that females do. Hence, building a law or business career is automatically seen as significant, while raising children or being a nurse are seen as somehow not so important. Is a critical attitude toward this kind of categorization encouraged at Dartmouth? Or does the curriculum implicitly endorse this type of categorization by validating men and men's achievements while ignoring women and women's achievements? What does this communicate to men and women alike about the possibilities for their lives? What does it say to men and women about their respective potentials and their respective worth?

These are questions that arise when you attempt to answer the question "Why study women?" and at Dartmouth ten years after the advent of coeducation, they are questions that need to be asked.

1. An American social reformer and pacifist born in1860, this woman won the Nobel Peace Prize in1931 and was regularly ranked first on lists of"America's greatest women." She died in 1935.

2. Born in 1920, this English scientist died ofcancer in 1958.

3. This English author, whose best-selling novelwas written when she was 19, was born in 1797and died in 1851.

4. This indomitable English Quaker, who bore 16children, was born in 1780 and died in 1845.

5. A Nobel Laureate, this French chemist lived from1897 until 1956 and had a famous mother.

6. Belgian by birth, this patriot of France, shownhere in her famous red silk riding habit, was born in1762 and died in 1817.

7. Born in Erlangen in 1882, this German scientist fled the Nazis and was received in this country,where she died at Bryn Mawr in 1935.

8. An American philanthropist born in Massachusetts about 1830, this woman worked for a time ashead of the Patent Office in Washington, D.C.

9. This American chemist, born in 1842, was thefirst woman admitted to M.I.T., from which shegraduated in 1873 . She died in 1911.

10. Born in 1879, this American visionary andfeminist theoretician founded the law-breaking journal The Woman Rebel. She died in 1966.

11. This American musician, born in 1910, spentthe major part of her remarkable career in KansasCity.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHome, Home on the Plain

October 1982 By Jeffrey Boffa -

Feature

FeatureCan the Summer?

October 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Sports

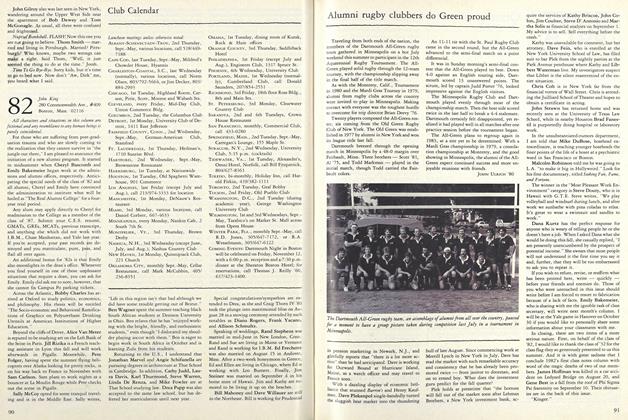

SportsAn Irish Connection and a Quaker Shutout

October 1982 By Brad Hills '65 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1982

October 1982 By John King -

Article

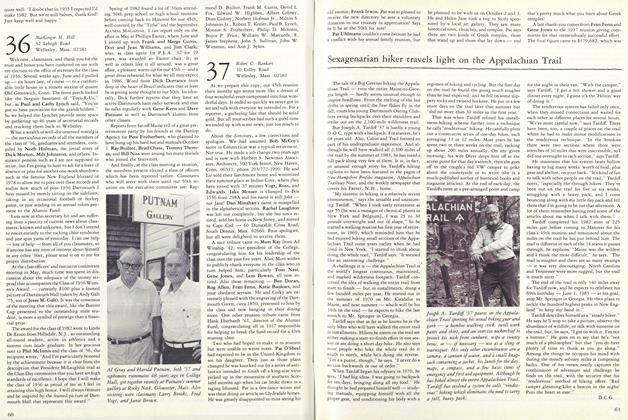

ArticleSexagenarian Hiker Travels Light on the Appalachian Trail

October 1982 By D.C.G -

Class Notes

Class Notes1945

October 1982 By Austin B. Wason

Mary Ellen Donovan

-

Feature

FeatureThe Lady and the Truckers

October 1978 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeaturePornography in Our Time

October 1980 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureHard times in the pressure-cooker

DECEMBER 1981 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Cover Story

Cover StoryPicking books Classic title, quirky tastes

MARCH 1982 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureOn Building Community

DECEMBER 1982 By Mary Ellen Donovan

Features

-

Feature

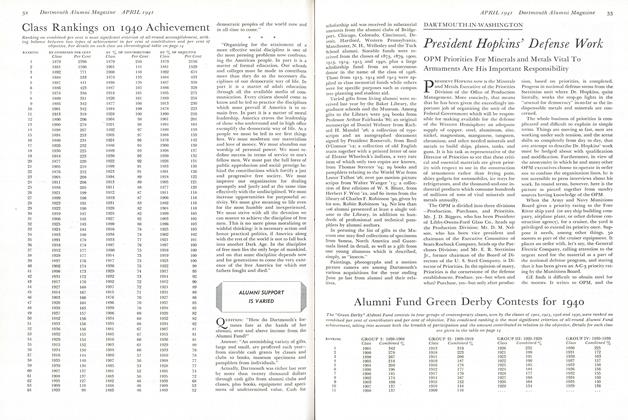

FeatureAlumni Fund Green Derby Contests for 1940

April 1941 -

Feature

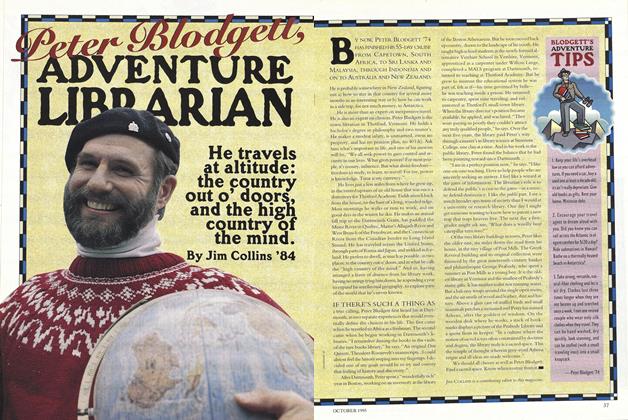

FeaturePeter Blodgutt, Adventure Librarian

October 1995 By Jim Collins '84 -

Feature

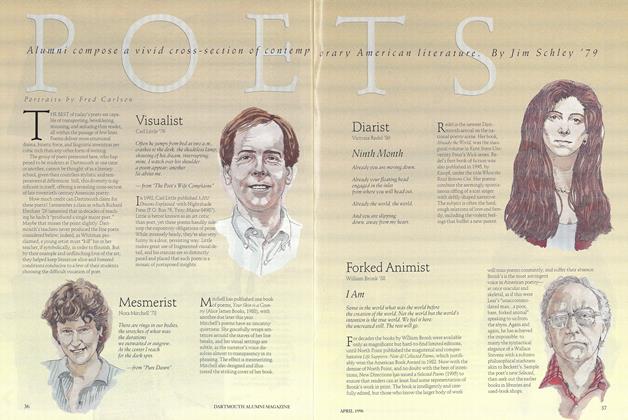

FeaturePOETS

APRIL 1996 By Jim Schley '79 -

Feature

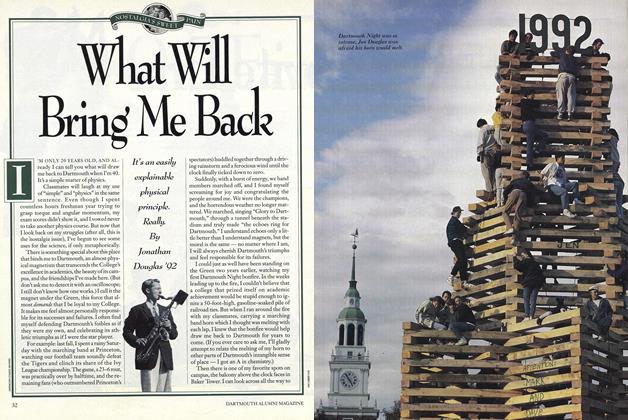

FeatureWhat Will Bring Me Back

MARCH 1991 By Jonathan Douglas '92, Richard Hovey -

Feature

FeatureThe Meaning of a Liberal Education

December 1955 By PROF. ARTHUR E. JENSEN -

Feature

FeatureVerdict on the Dartmouth Institute: A-OK

OCTOBER 1972 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40