WHEN I contacted Edward J. Shanahan, Dartmouth's new dean of the College, in November about an interview for the ALUMNI MAGAZINE, the only mutually convenient time we could find was 3:30 on a Saturday afternoon. It was the Saturday of the Columbia game, and, midway through the interview, the Baker bells began to peal. After they had pealed for what seemed a remarkable amount of time, I stopped the tape recorder. Nodding in the direction of the sound, I said, "Well, I guess Dartmouth won." Shanahan's face grew quizzical. "You mean the bells don't ring like that everyday?" he asked. "Nope," I said. "That only happens when the team has won. It's one of the codes." Shanahan considered this for a moment. "It's always helpful to know the codes," he said.

Shanahan comes to Dartmouth from Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut, where since 1977 he has been dean of students. His appointment as Dartmouth's eighth dean of the College was made in September and took effect December 1. During the fall, he spent his weekdays finishing up at Wesleyan and his weekends in Hanover, getting settled with his wife Kristi and their two children.

An affable, easy-going man of 39, Shanahan seems equally comfortable talking about philosophy and the more mundane problems of campus housing. He radiates warmth and a very human and humane sensitivity, and he is not afraid to speak the language of emotions all qualities that impressed those of us alumni who interviewed him during his candidacy for the deanship. Moreover, Shanahan seems a quick learner, particularly of "codes." For example, the afternoon of our interview, he just happened to be wearing, a dark green turtleneck over dark green (and very preppy) plaid trousers. When I commented on the aptness of his attire, he responded in an equally apt and very deanly voice. "If you mention that," he said, "I'll kill you."

Dean Shanahan, Why don't you begin bytelling me how you got into what you Ye doingnow and what keeps you doing it?

Okay. I started off being interested in a career in higher education when I went to graduate school to get a doctorate in English literature. That was my goal as well as becoming a professor within a college community. In order to finance my education, I became a resident adviser and a head resident at two separate institutions, one Fordham at which I studied for my master's and the second the University of Wisconsin at which I studied for the doctorate. As a result I found myself thinking about higher education in a broader context than I had thought about it up until that time. When I went to college there was certainly an academic side and an unacademic side of me, and I never thought of education as something holistic. But when I began to work as a resident adviser and had to teach freshmen and sophomores, juniors and seniors how to integrate what they were doing in the classroom with their living situations or with what was happening to them day in, day out; when I had to try to help them reconcile with their classroom learning the different priorities that they were discovering in their interactions with each other, I began to discover that very often what was happening in the classroom did not automatically relate to what was happening outside of the classroom, and vice versa. For example, somebody could be studying the ethics of building a community in a sociology course and come back to the dormitory and not do anything in the dormitory that would implement some of those things.

Or actually do something that was incontradiction.

That's right. Similarly, somebody could have had on Monday morning a most profound experience having to do with family or an interpersonal relationship and Monday afternoon be sitting in a class in which family is being spoken about, and there isn't any connection made. So, I said, this is an area of higher education that I find truly fascinating, and there's truly a need for help in bringing those two together.

You've used the term "holistic." Would youexplain holistic education? I imagine that inthe answer you will get to what has been perceived to be a problem at Dartmouth, specifically that there is historically has been toobig a gap between what goes on in the classroomand what goes on in people's lives.

I think there are a couple of dimensions in holistic education, and certainly you've touched on one of them. And that is to try to bridge that gap between what happens in the classroom and what happens outside of the classroom. In some cases, the connection isn't immediately apparent. For example, you might read a poem by John Donne and not immediately see how this will affect your roommate or your interaction with your roommate. But it should affect, to a certain extent, your attitude toward life, your appreciation for art or a specific artistic medium, and that should somehow affect the kind of relationship that you have with your roommate. Other connections between the classroom experience and what happens outside of the classroom are more easily made, for example, in the social sciences. That's the easiest place to see them quickly.

There is another relationship that's an important one, and that is the relationship between what happens in the classroom or on the campus and what's happening in the world. There is a certain nostalgia, I think, that exists for the halcyon days when one went to college and separated oneself from the concerns of the world and simply pursued learning and then left those hallowed halls and went back into society and tried to improve society. Now, I think that that's an important experience. And I hope that colleges still provide that experience at some times and in some places, because I think that uninterrupted study and separation from the distractions of the outside world are very important things. They allow one to concentrate on things in a way that perhaps is not possible outside. But I think it is also important to connect what is happening on campus to what's happening in the world, because the academic community's ideas have a great deal to do with what goes on in society. Moreover, I think that faculty members and students can do a great deal to improve the fabric of society by encouraging the application of what happens in the classroom to what happens outside the classroom. For example, I think it would be a mistake not to make connections between what happens in the business and governmental sectors and philosophical notions of ethics and morality.

Holistic education, at least in my definition of it, is one that takes into consideration the whole person: the emotional side of the individual, the social side of the individual, as well as the cognitive side of the individual.

You mentioned resident advisers and headresidents, and my understanding is that theyplayed a crucial role at Wesley an in implementing your philosophy of holistic education. Canyou explain what you did a bit more?

When I got there, there was a system that may be comparable to the undergraduate adviser system at Dartmouth. Juniors were selected on the basis of a one-page application submitted to the dean's office, and they were generally responsible for making sure the transition from high school to college was smooth, that the first-year students knew where the buildings were, where the faculty offices were, and how important academics were. But they didn't do a lot of programmatic work in the dormitories, didn't try to implement a philosophy in the dormitories. They simply tried to make sure that wherever there was discomfort in the transition, that discomfort was taken care of.

What I wanted to do was to develop more of a sense of community in each of the dormitories that we had at Wesleyan. Sometimes rituals can help do that football games, convocations, those sorts of things. But day-in-day-out community was not at Wesleyan, and in my judgment the best way to build a community is through people. If the cornerstone of your community is going to be people, then the way you build community is people. You don't build it through architecture. Architecture can help or hinder community, but it isn't going to build community. I needed to have a resident staff program that was going to have a philosophy of community development.

What kind of training is given advisers?

There is a week-long orientation for the 60-odd undergraduate resident advisers, two weeks for the 11 or so head residents. The first night and the first day are spent doing community development activities, some of which might seem kind of corny. The first night, for example, everybody stands up in front of the room, in front of everybody else in a big circle, introduces himself or herself, looks around, and really drinks in the attention of everybody else and then talks about a high point of the past summer. That takes four hours, and you'd be surprised how quickly the group gets together after that simple experience. Then the next day the group talks about the importance of safety in the dormitory - not safety from a public safety or security point of view, but safety from the point of view of the dormitories as places where people can be themselves and not be what other people expect them to be or what they think other people expect them to be. Very often students come to college with a pre-set mythology about who they are and what college is, and they spend a great deal of time trying to realize that mythology. And they are terrified by it. They will not go back to the dormitories and say I'm worried, I'm scared, 1 shouldn't be here, I miss home, I don't know if I want to be in college, I'm having difficulty with a relationship, I don't know whether I'm gay they will not do that unless an atmosphere is set in which people can reveal who they are. It's important if you're going to build community to build it on the firm foundation of reality and not on the mythologies that people have.

After the community building come crisis intervention and counseling skills and then program development and how to use programs to build the community. Half a day is spent on the notion of the relationship between programming and intent. Very often people who put on dorm programs don't ask themselves what they are trying to accomplish. Because if they asked themselves what they are trying to accomplish, they wouldn't put on the same type of dorm program. They wouldn't simply think about turning out the lights, turning up the music, and letting the booze flow not if they wanted people to get to know each,other. It's kind of hard to get to know people when you can't see them and you can't hear them. So the connection between programming and intent has to be made. And the third aspect is concern for the physical plant of the building.

Do you have plans for a similar program atDartmouth?

I would say that if these things are not here now (and I have some reason to believe that they may be starting to appear at Dartmouth), they are so basic that they should be here. I don't mean this in the sense that a particular program or a particular instrument or a particular activity may be appropriate here. I mean it in the sense that community development, safe home environment in the dormitories, counseling not just staff-student counseling, but student-student counseling are so fundamental to any residential college that not to have them here in some form or another would be, I think, a mistake.

What are your plans for specific changes onthe campus? I've heard a lot about cluster plansand new dormitories, and I'm in the dark.

I may be in the shade, if you're in the dark. I don't know a great deal about the specifics relating to the proposals that have been discussed. But the proposals that I have heard discussed to date have to do with the clustering of dormitories. What that is, in a nutshell, is simply taking some of the smaller units and having them relate architecturally to one another. So instead of having two or three units of a hundred students each, you've got three units of a hundred students each that are related architecturally to each other and are woven into a single community of 300 people.

What about fraternities?

There's a range of feelings there. Some people want to close fraternity houses I've sensed that on the campus and others, with whom I would associate myself, want to work with fraternity houses to see if their contribution to campus life can't be improved over what it currently is. I'm concerned with the physical condition of the houses, the kind of interactions that occur within them, and kind of interaction that occurs between the houses and those people who are outside. I think that a lot can happen there, a lot more than currently occurs.

Can you give an example?

I don't think fraternity presidents like to see their houses deteriorating under them. I don't think they like to see them trashed on the weekends when there are parties. But I think that they need some help from the business office and from the dean's office on how to organize the houses so that they are effective. I would also like to have some influence within the houses, although I don't kow whether this is possible at Dartmouth. For example, I would like to have something analogous to a resident adviser living in a frat house. Because if community development is going to happen through people, who are going to be specially trained in how to do this, then I think not to have them living in frat houses is to leave the houses to develop a kind of community that may be missing the mark in some respects. If the frat houses get their physical plants back in shape, then we need somebody working with the presidents or through some house advisers in getting the programmatic side of the house improved.

How do you get the physical plant intoshape? I wasn't in a fraternity, but I know ithappens a lot that someone who was in a fratcomes back 15 years later with spouse and kidsand says, "Oh, what a pigsty! I can't take myfamily in there." How would you go aboutencouraging the fraternities to clean up theplants?

I think there must be some set of standards that fraternities are encouraged to adhere to, some set of standards pertaining to the physical condition of the house. I think an important thing will be to articulate them with some degree of force and to encourage the houses, in conjunction with the alumni, to come up with a program of getting the houses to conform to them.

What Jo you mean by "articulating withforce"? Laying down the law?

At Wesleyan, we developed a set of standards with the cooperation of a number of other colleges, and we talked about it in the frat council, and the board of presidents accepted it. We then had an inspection of the houses a couple of times a year. It wasn't the kind of inspection that everybody worried about. It was the dean walking through the house with the house officers and getting a sense of what the problems were and what the students wanted to do about it and then working with the students in order to improve those conditions. In some instances, the dean's office got on the phone to the alumni and said, "We need some help with this house." In some instances, I went to the institution and said, "This is a good house. They need a short-term loan or a long-term loan in order to make some improvements." So it was addressed in the spirit of cooperation with the belief that everybody wanted to have an attractive and comfortable house to live in. And in that sense, it didn't have to be heavy-handed or a laying down of the law. There may be houses, however, that will not be at all sympathetic to these kinds of things, and the level of encouragement may have to be a little heavier with those houses.

You've been talking about community development, building a community. This is not specific to Dartmouth, but a proble?n here has beena lack of communication and community between different student groups, particularlyblack students and white students. My understanding is that Wesleyan was highly rated inthe recently published Black Student's Guide to Colleges. So I was wondering if you haveany feelings about encouraging community andtolerance at a campus like Dartmouth. A tolerance for people's being different from the WASPmainstream. Recently, for instance, Jewish students on campus finally came out and said,"We have not felt at home here." And this hasbeen a longstanding problem with black students, Native Americans, gays.

That's a good question and it's a terribly important point and I have some thoughts on it, but I don't think I have anything that I would call solutions to it. I think it's a perennial problem, the problem of intol- erance within a social organization. There are things an institution like Dartmouth can do to make improvements in that area, and I'd like to try to do some of those things. It certainly is important to have faculty, outside speakers, people within the community regularly addressing the dangers that are associated with intolerance in the world community or any kind of community.

We can, however, lecture students to death on the importance of tolerance within a community, and if we don't make the connection between that lecture and what's happening on campus, we have a difficulty. Students need an opportunity to talk about what their feelings are, what their reactions are. What do you feel when you experience somebody who is different from you? What conclusions do you draw? If students don't have an opportunity to articulate those things, they won't be corrected. They won't be enlightened. So I would hope that one of the programs that would occur in the dorms would be smallgroup discussion of some of these issues. Not only from a cognitive point of view, but from an affective or emotional point of view as well. And I hope to do some of that through the resident staff program. Don't expect, in a room of 300 people, somebody to stand up and say, "This is how I feel. They simply will not, because they're too attuned to being able to impress the people that they're sitting with. But take those people and sit them down in their homes, their dorms, and put them with 15 other people, and then I think you'll get at some of the feelings and the attitudes behind those feelings.

In this particular historical epoch, people in college are generally very much concerned about themselves. When I went to college, they were certainly concerned about themselves, but they were also concerned about ideas and ideals and the larger community. The Peace Corps got started and a lot of things happened back then that were clearly evidences of this community attitude. But this seems to have changed. I think, for example, that people' are more comfortable articulating racist comments today than they were ten years ago, and that's troublesome to me.

Dartmouth's stated purpose is to educateyoung persons with the ability to make "a significant contribution to society." It's a muchbandied-about phrase. What -would you hopestudents would leave Dartmouth with? A senseof what kind of values?

I would hope that they would graduate from Dartmouth with the ability to read and to write and otherwise to communicate. I think that to graduate from a college without having those basic communication skills and an appreciation for them - I think that would be a mistake. I also hope that the Dartmouth graduate would be able to see the importance of individual self-sacrifice in the interest of community growth and development. I would hope that a person would not graduate with skills and intellectual acumen and use those skills and acumen solely for the purpose of self-aggrandizement.

But also, I think that to talk about making improvements to society and contributing to society without personal expense is to mislead, and I think sometimes we do that. I think we tell students you can leave Dartmouth and you can make substantial contributions to society and you can realize everything that you wanted for yourself at the same time. If we don't instruct students in the importance of personal selfsacrifice in the interests of other people and in society as a whole, then I think we've made a mistake. So I'd like to see a Dartmouth graduate who's quick out there to remind people of the importance of that. And graduates who implement that in their everyday lives. I'm not talking necessarily about the person who goes into the Peace Corps, I'm talking about the person who happens to run the keypunch machine in a computer center or somebody who decides to become a carpenter. And I would hope that college would be good training for good family members. I'm not talking necessarily about parenting; I'm talking about just being members of a family.

Related to what you're saying, I think, is therealization that there is no such thing as a "selfmade man." That's a big myth in our society.But the reality is that there are always a lot ofpeople who enable the visible successes of a few.

I think that's true. A lot of people are contributing to everybody's worth and well-being. I think people who graduate from Dartmouth have a debt that they owe not just to Dartmouth and to the alumni who have made good contributions to the College over the years. They have a debt to everybody who's here to the instructors, certainly, but also a debt to the people who take care of the campus. And I think not to recognize that debt is to have an inflated sense of self-worth that can mislead people into false senses of their own importance.

I want to end by asking you about somethingthat's related. An earlier time I talked to you,you mentioned that you felt that students atDartmouth should have a sense of their ownprivilege.

I think that, to be sure, anybody who receives a Dartmouth education is privileged. There are very few people in the world who have the luxury of having thousands and thousands of dollars to spend on their education. Not just thousands of dollars that they have paid out of their own resources or their family resources, but thousands of dollars that have been contributed by taxpayers in some instances and thousands of dollars that have been contributed by generations and generations of alumni and benefactors of the College. There are very few people on the face of the earth who have the privilege of being able to reap the benefits of all that labor and all that capital investment. But I think in a college community we are not very conscious of the privilege because it's a daily experience. So I think we need individuals within that community administrators, faculty and other students who regularly remind us of how really fortunate we are. I think if we know that, if we're reminded of that regularly, we'll quickly see that it entails the responsibility of making sure that other people have access to this kind of education, or the responsiblity of doing something for that society that has given us this privilege.

Mary Ellen Donovan '76, a free-lance writernow living in Plainfield, New Hampshire,was a member of the search committee that recommended Edward Shanahan for the post ofdean of the College at Dartmouth.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWhere They Hang Their Hats

December 1982 By Steve Farnsworth and Jean Korelitz -

Feature

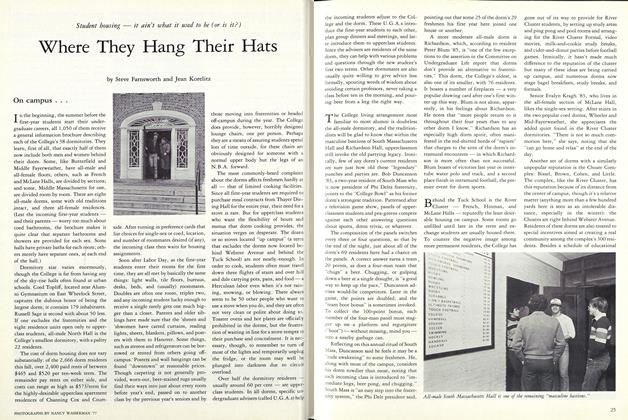

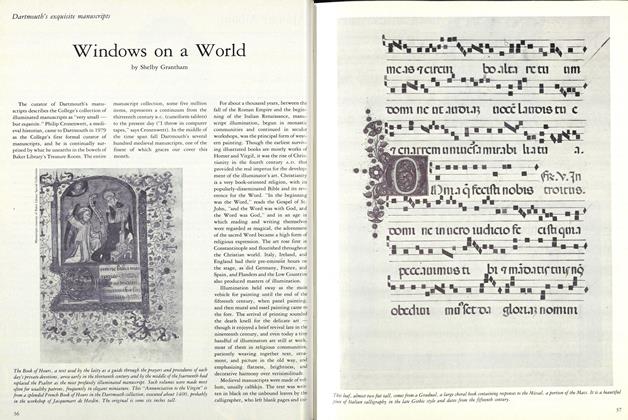

FeatureWindows on a World

December 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Article

ArticleDartmouth in the World

December 1982 -

Article

ArticleRound the Girdled Earth...

December 1982 -

Article

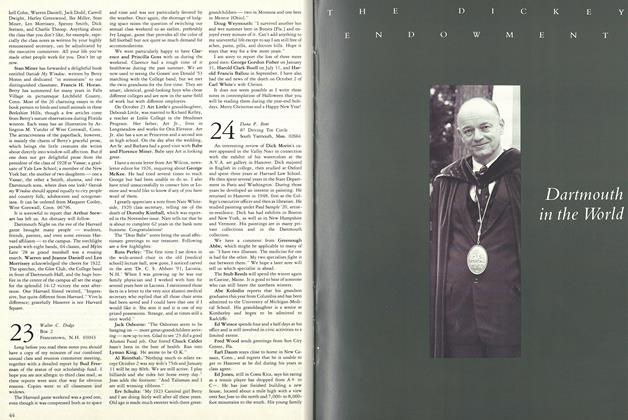

ArticleTHE DICKEY ENDOWMENT

December 1982 -

Article

ArticleOff to a Good Start.

December 1982 By Bernard D. Nossiter '47

Mary Ellen Donovan

-

Feature

FeatureThe Lady and the Truckers

October 1978 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeaturePornography in Our Time

October 1980 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureHard times in the pressure-cooker

DECEMBER 1981 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Cover Story

Cover StoryPicking books Classic title, quirky tastes

MARCH 1982 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureWHY STUDY WOMEN?

OCTOBER 1982 By Mary Ellen Donovan

Features

-

Feature

FeatureSix Professors Reach Retirement

JUNE 1970 -

Cover Story

Cover StorySupply & Demand

July/Aug 2010 By C.J. Hughes ’92 -

Feature

FeatureUnforgettable!

Sept/Oct 2007 By HOWARD LEAVITT ’43 -

Feature

FeatureGame Changer

NovembeR | decembeR By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

FeatureSafe Haven

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2019 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

FeatureA winter of discontent, a day of perceiving differences

April 1979 By Shelby Grantham