THE PAPERS OF DANIEL WEBSTER Correspondence, Vol. IV, 1835—1839 1980. 588 pp. $35 Correspondence, Vol. V, 1840—1843 1982. 618 pp. $35 Legal, Vol. I, New Hampshire Practice 1982 . 600 pp. $35 Legal, Vol. 11, Boston Practice 1982. 700 pp. $31.50 University Press of New England

In a corner of Dartmouth's Baker Library and at the Harvard Law School in Cambridge there toil a handful of people engaged in one of the more arcane cottage industries of scholarship, the editing under the general direction of Charles Wiltse, of the documentary legacy of Daniel Webster. It is slow work, tiring and tedious, but lately the product of that labor, so essential to the work of the historians of the future, has come forth in gushes rather than trickles. These four volumes claim to add little to the reservoir of knowledge about the most storied, and beloved, member of Dartmouth's class of 1801: their contribution, however, is far more subtle and not at all insignificant, for, literally, they put within the reach of the historian, the hobbyist, and the curious many of the travails and triumphs of the man who, for the first half of the last century, came to symbolize what America meant.

These volumes cover important periods in Webster's life: his legal training and his early life in the law, his practice in the rural communities of New Hampshire and the mercantile community of Massachusetts and, as a theme running through Webster's life, the loss of innocence and the gain of ambition. These, too, were the years when he confronted his twin ambitions, his lusts for riches and for the presidency.

But sprinkled through the correspondence, edited by Wiltse and Harold Moser, amid the talk about the Bank of the United States, tariff matters, public land questions, the Webster-Ashburton Treaty and the crisis prompted by the resignation of all of John Tyler's cabinet save Webster, there are the occasional insights into the private Webster, into the tiny impulses that animated him, and into the warp and woof of life in the capital and Congress of the young Republic. These also deserve attention, for despite a series of careful biographies in recent years, Webster seems destined to be known beyond the walls of scholarship more as a myth than as a man.

There is, in these volumes, the lament of the striving young lawyer, worrying that he is "growing rusty, in general knowledge" and fearing that "unless I can find, or make, some leisure from my office, I shall shortly be neither more nor less than an attorney." There is Webster, who spent much of his own life in debt, chastising his son Edward, a Dartmouth student, for falling into debt and remonstrating acidly, "I now trust, My Dear Son, to hear nothing of you, hereafter, except what may be gratifying." And there is Webster, in a letter to his wife in 1836, confessing his boredom with the legislative.life: "There is nothing of interest in Congress, & as I do not go out at all, & for a month have asked nobody to my rooms, life has become a little too solitary."

The legal papers, edited by Alfred S. Konefsky and Andrew S. King, the only portion of the Webster project to be undertaken outside Hanover, add further to this mosaic. Here we find the young Webster questioning his choice of the legal profession and then, once set on it, approaching it with vigor. In maturity he assumed increasing numbers of the contract and commercial cases that gave lawyers their economic stability and that nurtured his allegiance to the business interests of the nation. But these values serve as a reminder that the man who spoke to the weighty questions of antebellum America began his professional life like so many others of his generation and ours, amid the questions of debt collection and creditor rights.

It was, perhaps, the quiet and somewhat unobtrusive work of the town lawyer. The meaning of those years, and these documents, transcends that, however. In Webster's case and, especially, in Webster's time, these issues were helping to define the country by establishing the legal underpinnings of a society that was still only emerging.

David Shribman, a reporter in the Washingtonbureau of The New York Times, has writtenabout Daniel Webster in this issue of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature'Far Out and Daring': Dartmouth Abroad

September 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

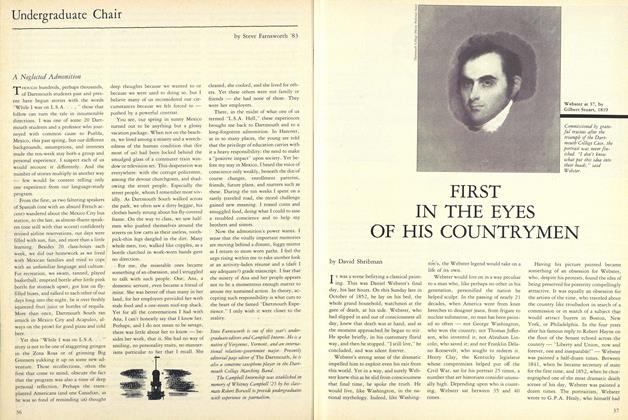

FeatureFIRST IN THE EYES OF HIS COUNTRYMEN

September 1982 By David Shribman -

Class Notes

Class Notes1957

September 1982 By Daniel M. Searby -

Article

Article"Man Better Man"

September 1982 By Nardi Reeder Campion -

Sports

SportsHelp Wanted: Rising Sophomores

September 1982 By Brad Hills '65 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1977

September 1982 By Walter M. Wingate Jr., Lindsay Larrabee Greimann '77

David Shribman '76

-

Article

ArticleSpy in the Cold

October 1975 By DAVID SHRIBMAN '76 -

Article

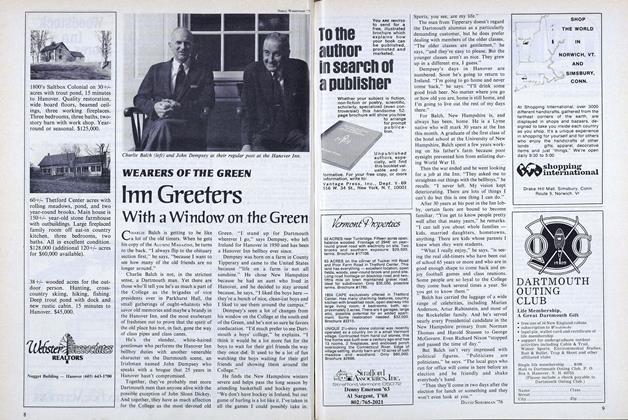

ArticleInn Greeters With a Window on the Green

December 1975 By DAVID SHRIBMAN '76 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Album

MARCH 1983 By David Shribman '76 -

Article

ArticleThe Last Hurrumph

APRIL 1997 By David Shribman '76 -

Features

Features“His Life Was a Gift”

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2023 By DAVID SHRIBMAN '76 -

notebook

notebookA Man of Letters

MAY | JUNE 2024 By DAVID SHRIBMAN '76

Books

-

Books

BooksTUKARAM

April 1931 -

Books

BooksThe Classical Weekly

FEBRUARY 1932 -

Books

BooksOUR ARTISTIC WORLD

December 1942 By Arthur M. Wilson -

Books

BooksELECTRICITY AND MAGNETISM

March 1933 By C. A. P -

Books

BooksTHE JACQUES ROMANO STORY.

OCTOBER 1968 By EDWARD M. POTOKER '53 -

Books

BooksTHE FUTURE LIKE A BRIDE.

July 1958 By PAUL LAUTER