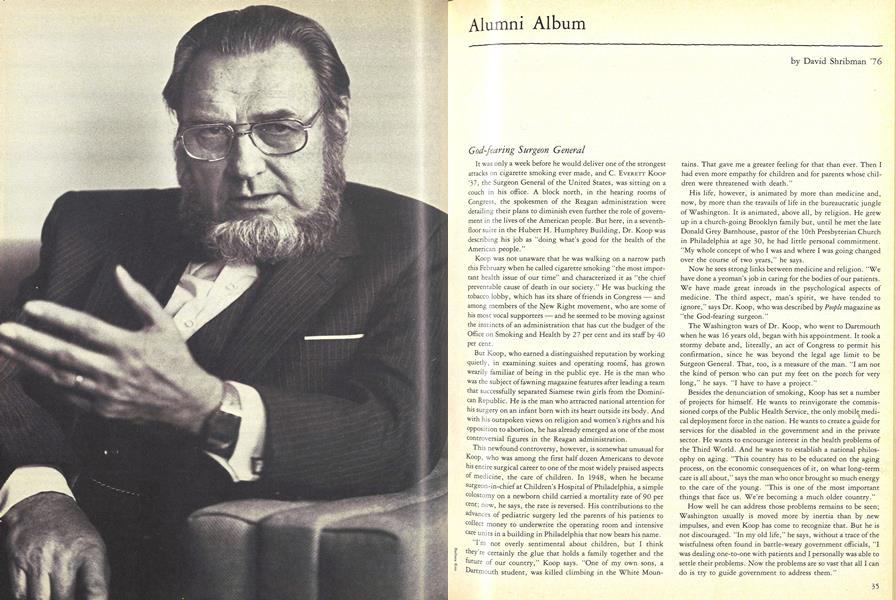

It was only a week before he would deliver one of the strongest attacks on cigarette smoking ever made, and C. Everett Koop '37, the Surgeon General of the United States, was sitting on a couch in his office. A block north, in the hearing rooms of Congress, the spokesmen of the Reagan administration were detailing their plans to diminish even further the role of government in the lives of the American people. But here, in a seventhfloor suite in the Hubert H. Humphrey Building, Dr. Koop was describing his job as "doing what's good for the health of the American people."

Koop was not unaware that he was walking on a narrow path this February when he called cigarette smoking "the most important health issue of our time" and characterized it as "the chief preventable cause of death in our society." He was bucking the tobacco lobby, which has its share of friends in Congress and among members of the New Right movement, who are some of his most vocal supporters — and he seemed to be moving against the instincts of an administration that has cut the budget of the Office on Smoking and Health by 27 per cent and its staff by 40 per cent.

But Koop, who earned a distinguished reputation by working quietly, in examining suites and operating rooms, has grown wearily familiar of being in the public eye. He is the man who was the subject of fawning magazine features after leading a team that successfully separated Siamese twin girls from the Dominican Republic. He is the man who attracted national attention for his surgery on an infant born with its heart outside its body. And with his outspoken views on religion and women's rights and his opposition to abortion, he has already emerged as one of the most controversial figures in the Reagan administration.

This newfound controversy, however, is somewhat unusual for Koop, who was among the first half dozen Americans to devote his entire surgical career to one of the most widely praised aspects of medicine, the care of children. In 1948, when he became surgeon-in-chief at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, a simple colostomy on a newborn child carried a mortality rate of 90 per cent; now, he says, the rate is reversed. His contributions to the advances of pediatric surgery led the parents of his patients to collect money to underwrite the operating room and intensive care units in a building in Philadelphia that now bears his name.

"I'm not overly sentimental about children, but I think they re certainly the glue that holds a family together and the future of our country," Koop says. "One of my own sons, a Dartmouth student, was killed climbing in the White Mountains That gave me a greater feeling for that than ever. Then I had even more empathy for children and for parents whose children were threatened with death."

His life, however, is animated by more than medicine and, now, by more than the travails of life in the bureaucratic jungle of Washington. It is animated, above all, by religion. He grew up in a church-going Brooklyn family but, until he met the late Donald Grey Barnhouse, pastor of the 10th Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia at age 30, he had little personal commitment. "My whole concept of who I was and where I was going changed over the course of two years," he says.

Now he sees strong links between medicine and religion. "We have done a yeoman's job in caring for the bodies of our patients. We have made great inroads in the psychological aspects of medicine. The third aspect, man's spirit, we have tended to ignore," says Dr. Koop, who was described by People magazine as "the God-fearing surgeon."

The Washington wars of Dr. Koop, who went to Dartmouth when he was 16 years old, began with his appointment. It took a stormy debate and, literally, an act of Congress to permit his confirmation, since he was beyond the legal age limit to be Surgeon General. That, too, is a measure of the man."I am not the kind of person who can put my feet on the porch for very long," he says. "I have to have a project."

Besides the denunciation of smoking, Koop has set a number of projects for himself. He wants to reinvigorate the commissioned corps of the Public Health Service, the only mobile medical deployment force in the nation. He wants to create a guide for services for the disabled in the government and in the private sector. He wants to encourage interest in the health problems of the Third World. And he wants to establish a national philosophy on aging. "This country has to be educated on the aging process, on the economic consequences of it, on what long-term care is all about," says the man who once brought so much energy to the care of the young. "This is one of the most important things that face us. We're becoming a much older country."

How well he can address those problems remains to be seen; Washington usually is moved more by inertia than by new impulses, and even Koop has come to recognize that. But he is not discouraged. "In my old life," he says, without a trace of the wistfulness often found in battle-weary government officials, "I was dealing one-to-one with patients and I personally was able to settle their problems. Now the problems are so vast that all I can do is try to guide government to address them."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHotsy Totsy

April 1982 By Lomax Littlejohn -

Feature

FeatureThe Man Behind the Green

April 1982 By Rob Eshman -

Feature

FeatureEnd of a Golden era

April 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

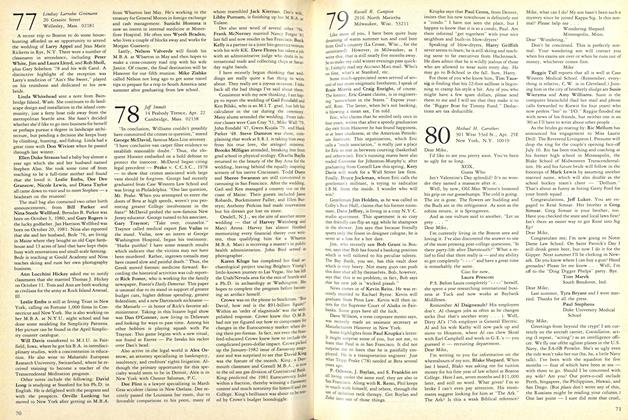

Cover StoryOn Mount Washington, where the Geum Peckii blooms and blows

April 1982 By Peter Heller -

Article

ArticleCONSTITUTION OF THE COUNCIL OF THE ALUMNI OF DARTMOUTH COLLEGE

April 1982 -

Article

ArticleSeer in the Dark

April 1982 By Mary Ross

David Shribman '76

-

Article

ArticleFrench Verbs and Javelin Throws

April 1974 By DAVID SHRIBMAN '76 -

Article

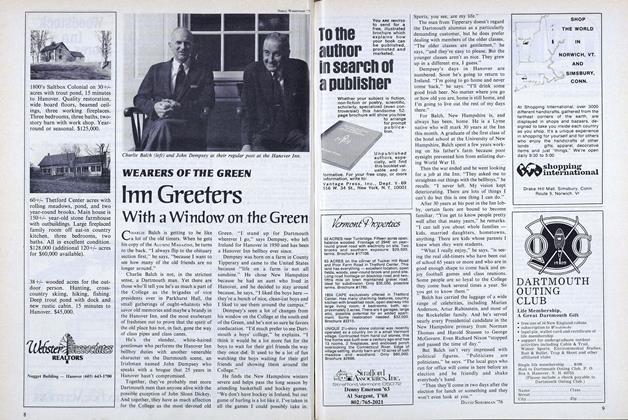

ArticleInn Greeters With a Window on the Green

December 1975 By DAVID SHRIBMAN '76 -

Article

ArticleReagan Revolutionary

DECEMBER 1981 By David Shribman '76 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Album

MARCH 1983 By David Shribman '76 -

Article

ArticleThe Last Hurrumph

APRIL 1997 By David Shribman '76 -

notebook

notebookA Man of Letters

MAY | JUNE 2024 By DAVID SHRIBMAN '76

Article

-

Article

ArticleINVESTIGATION OF DORMITORY SYSTEMS

May 1912 -

Article

ArticleSOCCER

November 1920 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Articles

May 1961 -

Article

ArticleRecent Gifts and Bequests to College Illustrate a Wide Range of Support

JANUARY 1967 -

Article

ArticleCollege Treasurer Resigning

FEBRUARY 1972 -

Article

ArticleMedical School

DECEMBER 1963 By HARRY W. SAVAGE M'27