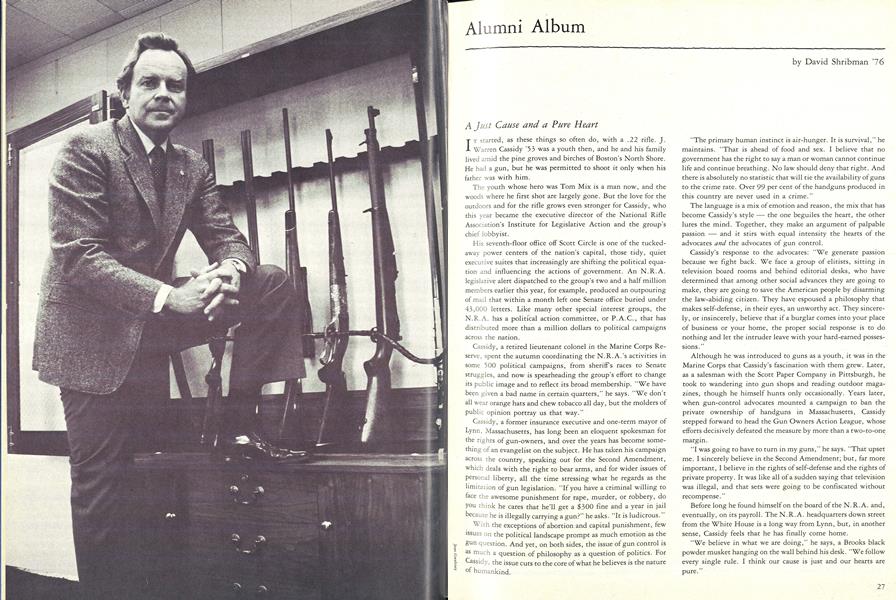

A Just Cause and a Pure Heart

IT started, as these things so often do, with a .22 rifle. J. Warren Cassidy '53 was a youth then, and he and his family lived amid the pine groves and birches of Boston's North Shore. He had a gun, but he was permitted to shoot it only when his father was with him.

The youth whose hero was Tom Mix is a man now, and the woods where he first shot are largely gone. But the love for the outdoors and for the rifle grows even stronger for Cassidy, who this year became the executive director of the National Rifle Association's Institute for Legislative Action and the group's chief lobbyist.

His seventh-floor office off Scott Circle is one of the tuckedaway power centers of the nation's capital, those tidy, quiet executive suites that increasingly are shifting the political equation and influencing the actions of government. An N.R.A. legislative alert dispatched to the group's two and a half million members earlier this year, for example, produced an outpouring of mail that within a month left one Senate office buried under 43,000 letters. Like many other special interest groups, the N.R.A. has a political action committee, or P.A.C., that has distributed more than a million dollars to political campaigns across the nation.

Cassidy, a retired lieutenant colonel in the Marine Corps Reserve, spent the autumn coordinating the N.R.A.'s activities in some 500 political campaigns, from sheriffs races to Senate struggles, and now is spearheading the group's effort to change its public image and to reflect its broad membership. "We have been given a bad name in certain quarters," he says. "We don't all wear orange hats and chew tobacco all day, but the molders of public opinion portray us that way."

Cassidy, a former insurance executive and one-term mayor of Lynn, Massachusetts, has long been an eloquent spokesman for the rights of gun-owners, and over the years has become something of an evangelist on the subject. He has taken his campaign across the country, speaking out for the Second Amendment, which deals with the right to bear arms, and for wider issues of personal liberty, all the time stressing what he regards as the limitation of gun legislation. "If you have a criminal willing to face the awesome punishment for rape, murder, or robbery, do you think he cares that he'll get a $300 fine and a year in jail because he is illegally carrying a gun?" he asks. "It is ludicrous.

With the exceptions of abortion and capital punishment, few issues on the political landscape prompt as much emotion as the gun question. And yet, on both sides, the issue of gun control is as much a question of philosophy as a question of politics. For Cassidy, the issue cuts to the core of what he believes is the nature of humankind.

"The primary human instinct is air-hunger. It is survival," he maintains. "That is ahead of food and sex. I believe that no government has the right to say a man or woman cannot continue life and continue breathing. No law should deny that right. And there is absolutely no statistic that will tie the availability of guns to the crime rate. Over 99 per cent of the handguns produced in this country are never used in a crime."

The language is a mix of emotion and reason, the mix that has become Cassidy's style the one beguiles the heart, the other lures the mind. Together, they make an argument of palpable passion and it stirs with equal intensity the hearts of the advocates and the advocates of gun control.

Cassidy's response to the advocates: "We generate passion because we fight back. We face a group of elitists, sitting in television board rooms and behind editorial desks, who have determined that among other social advances they are going to make, they are going to save the American people by disarming the law-abiding citizen. They have espoused a philosophy that makes self-defense, in their eyes, an unworthy act. They sincerely, or insincerely, believe that if a burglar comes into your place of business or your home, the proper social response is to do nothing and let the intruder leave with your hard-earned possessions."

Although he was introduced to guns as a youth, it was in the Marine Corps that Cassidy's fascination with them grew. Later, as a salesman with the Scott Paper Company in Pittsburgh, he took to wandering into gun shops and reading outdoor magazines, though he himself hunts only occasionally. Years later, when gun-control advocates mounted a campaign to ban the private ownership of handguns in Massachusetts, Cassidy stepped forward to head the Gun Owners Action League, whose efforts decisively defeated the measure by more than a two-to-one margin.

"I was going to have to turn in my guns," he says. "That upset me. I sincerely believe in the Second Amendment; but, far more important, I believe in the rights of self-defense and the rights of private property. It was like all of a sudden saying that television was illegal, and that sets were going to be confiscated without recompense."

Before long he found himself on the board of the N.R. A. and, eventually, on its payroll. The N.R. A. headquarters down street from the White House is a long way from Lynn, but, in another sense, Cassidy feels that he has finally come home.

"We believe in what we are doing," he says, a Brooks black powder musket hanging on the wall behind his desk. "We follow every single rule. I think our cause is just and our hearts are pure."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWhat Is Success?

March 1983 By E. R. (Skip) Sturman '70 -

Feature

Feature"Long John" Wentworth, 1836

March 1983 By Dirk Olin '81 -

Feature

FeatureYou know, what's his name . . ."

March 1983 By Nardi Reeder Campion -

Feature

FeatureOff and Chopping

March 1983 By Jean Hanff Korelitz -

Article

ArticleSetting the Record Straight: A Senior-Year Perspective

March 1983 By Libby Schmeltzer '83 -

Sports

SportsSports

March 1983 By Brad Hills '65

David Shribman '76

-

Article

ArticleFrench Verbs and Javelin Throws

April 1974 By DAVID SHRIBMAN '76 -

Article

ArticleSpy in the Cold

October 1975 By DAVID SHRIBMAN '76 -

Article

ArticleInn Greeters With a Window on the Green

December 1975 By DAVID SHRIBMAN '76 -

Article

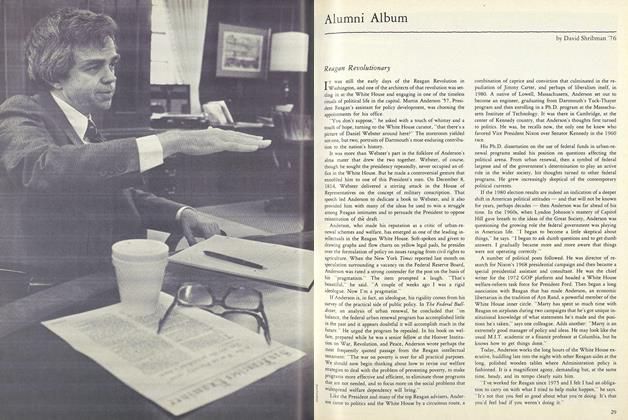

ArticleReagan Revolutionary

DECEMBER 1981 By David Shribman '76 -

Books

BooksAdding to the Mosaic

SEPTEMBER 1982 By David Shribman '76 -

Features

Features“His Life Was a Gift”

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2023 By DAVID SHRIBMAN '76