These days, there aren't many places I go without Jane. It seems as if we're always together, running along Rip Road in the mornings, drinking tea at Sanborn in the afternoons, and, of course, having long intimate discussions in my fourth floor Baker Library study. It isn't as if I don't get sick of her. Sometimes I feel as if I'll go nuts if I don't get away spend some time with my other friends, escape to Mew York or Boston for the weekend but with my honors thesis on Jane Austen due in only a few weeks, escape is a luxury I can't afford.

In the spring of my junior year, my major advisor in the English department told me he thought I should write an honors thesis. I gave him a flat refusal. "It's pure agony," a friend in the class of'81 had told me only days before. "And for what? I'm already into graduate school. I spent my entire senior spring in the library!" I had sympathized with her and privately resolved that my own senior spring would be a time to relax, to be with my friends before commencement sent us off in different directions. But that was before I met Jane. . . .

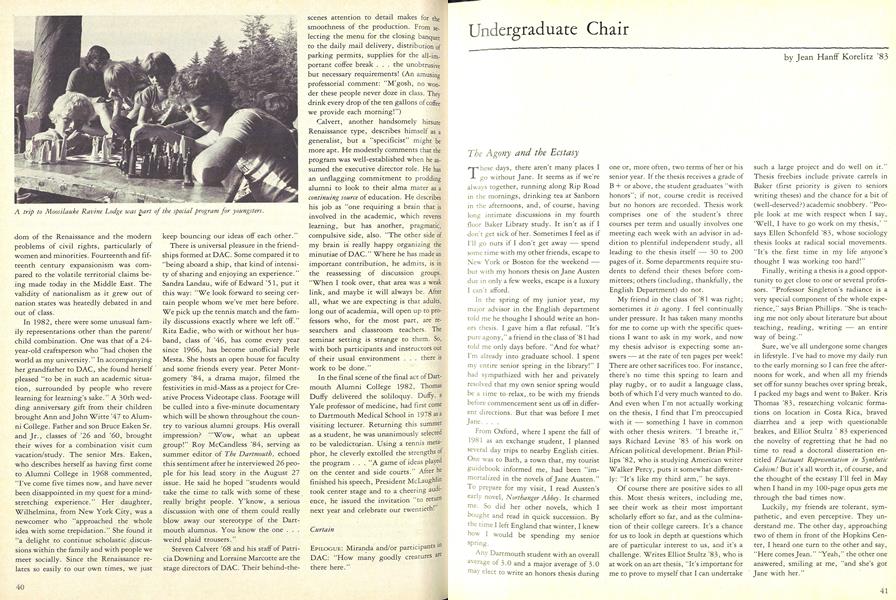

From Oxford, where I spent the fall of 1981 as an exchange student, I planned several day trips to nearby English cities. One was to Bath, a town that, my tourist guidebook informed me, had been "immortalized in the novels of Jane Austen." To prepare for my visit, I read Austen's early novel, Northanger Abbey. It charmed me. So did her other novels, which I bought and read in quick succession. By the time I left England that winter, I knew how I would be spending my senior spring.

Any Dartmouth student with an overall average of 3.0 and a major average of 3.0 may elect to write an honors thesis during one or, more often, two terms of her or his senior year. If the thesis receives a grade of B + or above, the student graduates "with honors"; if not, course credit is received but no honors are recorded. Thesis work comprises one of the student's three courses per term and usually involves one meeting each week with an advisor in addition to plentiful independent study, all leading to the thesis itself 30 to 200 pages of it. Some departments require students to defend their theses before committees; others (including, thankfully, the English Department) do not.

My friend in the class of '81 was right; sometimes it is agony. I feel continually under pressure. It has taken many months for me to come up with the specific questions I want to ask in my work, and now my thesis advisor is expecting some answers at the rate of ten pages per week! There are other sacrifices too. For instance, there's no time this spring to learn and play rugby, or to audit a language class, both of which I'd very much wanted to do. And even when I'm not actually working on the thesis, I find that I'm preoccupied with it something I have in common with other thesis writers. "I breathe it," says Richard Levine '83 of his work on African political development. Brian Phillips '82, who is studying American writer Walker Percy, puts it somewhat differently: "It's like my third arm," he says.

Of course there are positive sides to all this. Most thesis writers, including me, see their work as their most important scholarly effort so far, and as the culmination of their college careers. It's a chance for us to look in depth at questions which are of particular interest to us, and it's a challenge. Writes Elliot Stultz '83, who is at work on an art thesis, "It's important for me to prove to myself that I can undertake such a large project and do well on it." Thesis freebies include private carrels in Baker (first priority is given to seniors writing theses) and the chance for a bit of (well-deserved?) academic snobbery. "People look at me with respect when I say, "Well, I have to go work on my thesis,' " says Ellen Schonfeld '83, whose sociology thesis looks at radical social movements. "It's the, first time in my life anyone's thought I was working too hard!"

Finally, writing a thesis is a good opportunity to get close to one or several professors. "Professor Singleton's radiance is a very special component of the whole experience," says Brian Phillips. "She is teaching me not only about literature but about teaching, reading, writing an entire way of being."

Sure, we've all undergone some changes in lifestyle. I've had to move my daily run to the early morning so I can free the afternoons for work, and when all my friends set off for sunny beaches over spring break, I packed my bags and went to Baker. Kris Thomas '83, researching volcanic formations on location in Costa Rica, braved diarrhea and a jeep with questionable brakes, and Elliot Stultz ' 83 experienced the novelty of regretting that he had no time to read a doctoral dissertation entitled Fluctuant Representation in SyntheticCubism! But it's all worth it, of course, and the thought of the ecstasy I'll feel in May when I hand in my 100-page opus gets me through the bad times now.

Luckily, my friends are tolerant, sympathetic, and even perceptive. They understand me. The other day, approaching two of them in front of the Hopkins Center, I heard one turn to the other and say, "Here comes Jean." "Yeah," the other one answered, smiling at me, "and she's got Jane with her."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureAlumni College Retrospective

May 1983 By Jean Dalury -

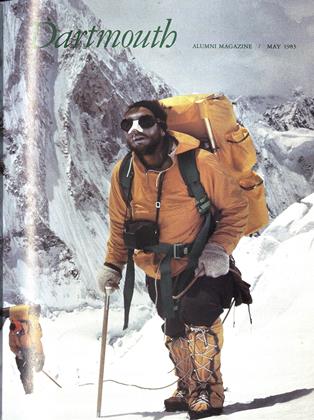

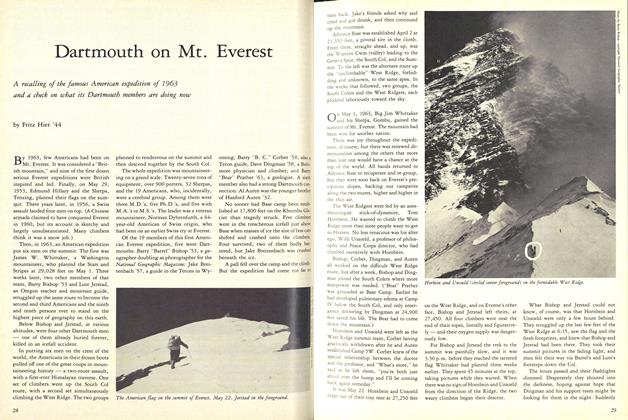

Cover Story

Cover StoryDartmouth on Mt. Everest

May 1983 By Fritz Hier '44 -

Feature

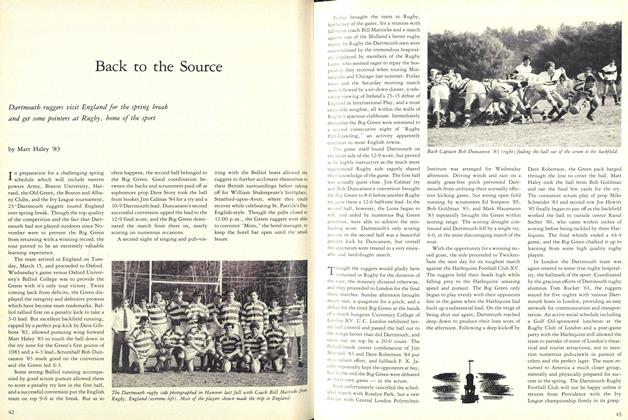

FeatureBack to the Source

May 1983 By Matt Haley '83 -

Cover Story

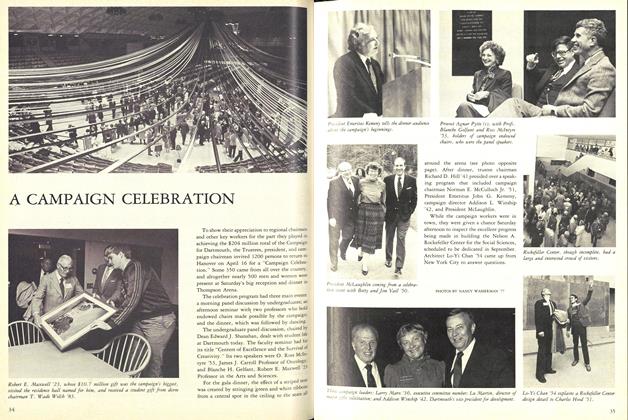

Cover StoryA CAMPAIGN CELEBRATION

May 1983 -

Sports

SportsSports

May 1983 By Brad Hills '65 -

Article

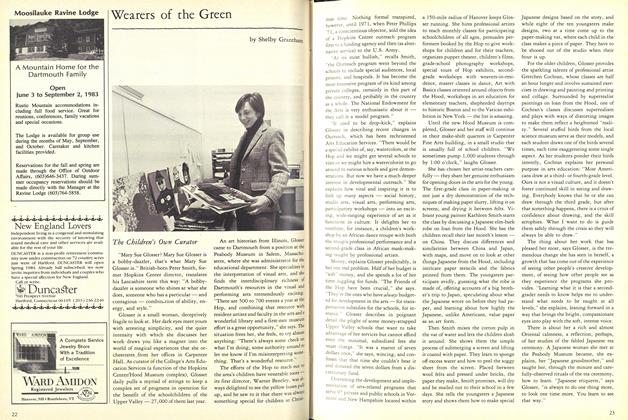

ArticleThe Children's Own Curator

May 1983 By Shelby Grantham

Jean Hanff Korelitz '83

Article

-

Article

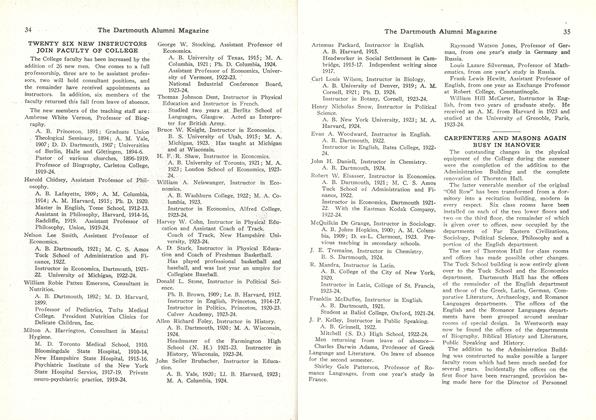

ArticleCARPENTERS AND MASONS AGAIN BUSY IN HANOVER

November, 1924 -

Article

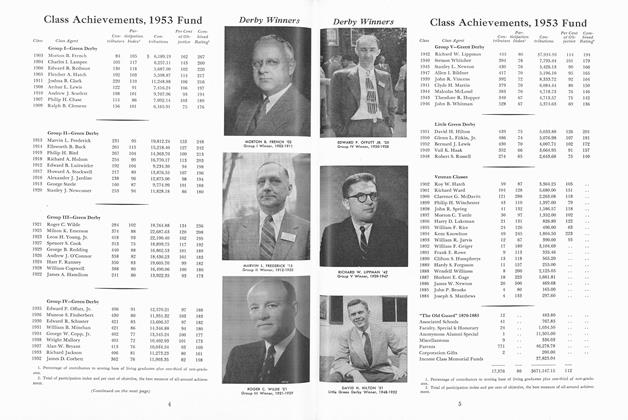

ArticleDerby Winners

December 1953 -

Article

ArticleGifts Recently Added To Baker Collections

March 1954 -

Article

ArticleGive a Rouse for

JUNE/JULY 1984 -

Article

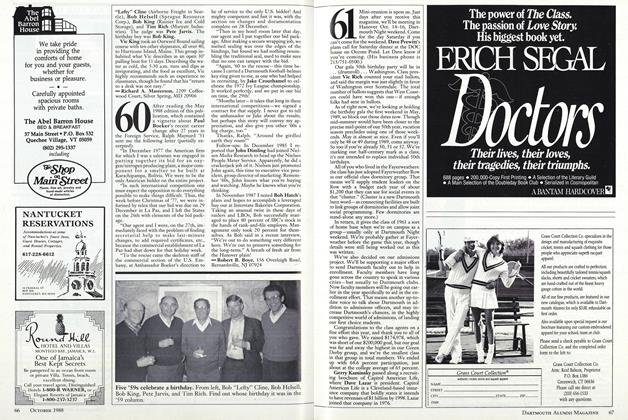

ArticleFive '59s celebrate a birthday

OCTOBER 1988 -

Article

ArticleGreen Jottings

May 1960 By CLIFF JORDAN '45