Many centuries ago, when I was a high school student looking at colleges, I remember crossing several off of my list because of what I termed "inadequate residential life" (I was very business-like in those days). At Johns Hopkins, for example, I was told that the vast majority of undergraduates moved off-campus after freshman year. Who needed that? I wasn't going to college so that I could live in an apartment; I wanted to live with and learn from many people from different backgrounds, and with different interests.

In the end, one of the major factors in my decision to come to Dartmouth was my perception of it as a working community. What else could you call a handpicked group of motivated, talented, and bright students who had come together to live in a beautiful New Hampshire haven? And I took it for granted that residential life at Dartmouth would reflect this ideal.

All right, so I was naive. Although I lived as a freshman in one of the more "spirited" dorms on campus, I quickly learned that, at Dartmouth, allegiance to dormitory takes a distinct back seat to allegience to fraternity or sorority. By freshman spring, I had lost track of the women who were living on my hall; the next door neighbors I'd become close to over the fall were on L.S.A. in Europe, and my new neighbors were back at Dartmouth after their own off-campus terms. The dormitory had a disjointed feeling. People were always packing or unpacking, and sometimes, because of shifting enrollment patterns, students returning to campus were not able to get back into our dormitory and were sent to different areas of the campus. No one attended dormitory meetings. The housing office did not allot much funding for social events, anyway.

By sophomore fall, I knew I would not live in a dormitory again. I spent two terms living in College-owned cooperative houses, where I did experience a sense of community, and then left Dartmouth for an exchange year at two other universities.

At one of them Harvard I became a member of Dunster House, a residential unit. All upperclass Harvard students live in houses, each of which has its own study space, resident master, faculty advisors, and facilities ranging from snack bars to photographic dark rooms and music rehearsal rooms. Once I saw how well the house system worked, I began to wonder if a similar system modified to accommodate the smaller student body and the Dartmouth Plan could not work at Dartmouth. I concluded that it could.

Meanwhile, back on the Hanover Plain, the Committee on Undergraduate Life was reaching the same conclusion and proposing that dormitories be grouped into residential "clusters."

Briefly, the idea is to create communities among Dartmouth's existing dormitories one or two new ones might have to be built by creating community space and facilities for each cluster. Space would also be made for a resident master and his or her family, and for resident faculty. Other faculty would be non-resident members of the cluster "family." Each group, in addition, would have its own student administration, the chair of which would sit on a College committee charged with overseeing the entire system.

As it stands today, the responsibility for social life at Dartmouth rests with the fraternities. The cluster proposal would allow the College to reclaim part of that responsibility. The clusters would sponsor a large variety of activities for their members, from singing groups to guest speakers and athletic teams, and they would work as communities beause students would choose which ones they wanted to live in. Upperclass students coming back to campus from leave terms might not be assigned to the same dormitory they had lived in before, but they would always be able to return to the cluster, and the familiarity of the faces in their corner of the campus would begin to counter the feeling of fragmentation engendered by the D-plan. Intramural sports and activities would be more active than they are now, and housing office funds, supplemented by student "cluster dues," would provide for several social events per term.

Student reaction has been mixed. Two things (in addition to our legendary resistance to change) are holding the proposal back. One is the idea that a cluster system must include certain clusters for first-year students only. As at Harvard and Yale, incoming students would live together as a class (with resident upperclass advisers) in these communities for their first year, and would then choose a cluster affiliation for their remaining Dartmouth years. The issue of segregating the freshman class is a difficult one, and I do not intend to address it here. I would like to stress, however, that it is possible to create a cluster system that would integrate all classes. First-year students could be randomly assigned and decide later whether to remain in the same cluster or to transfer to another.

A second factor holding back the proposal is apprehension about its effect on the fraternity system. Certainly, if clusters are successful in creating residential spirit and loyalties, the fraternities would no longer be providing the entertainipent for the entire campus, as they are now. It is conceivable that the fraternity system might shrink as the need for it shrank.

Currently, approximately one tenth of all Dartmouth students (including me) live off-campus. It is a figure that has gone up 50 per cent over the past four years: I am probably not the only person who feels this way about residential life at the College. That the residential clusters would lend variety and stability to life at Dartmouth seems to me obvious. I wish that a cluster system had been implemented years ago. If it had, I'd be living on campus. But since it was not, I support it now, in hopes of creating for succeeding Dartmouth classes the residential life I sought as a high school senior.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureOn Building Community

December 1982 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

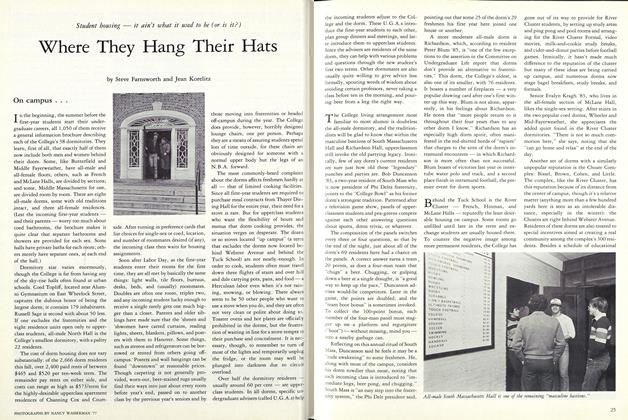

FeatureWhere They Hang Their Hats

December 1982 By Steve Farnsworth and Jean Korelitz -

Feature

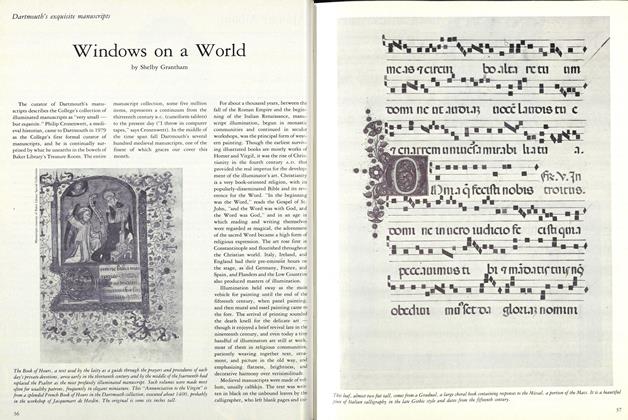

FeatureWindows on a World

December 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Article

ArticleDartmouth in the World

December 1982 -

Article

ArticleRound the Girdled Earth...

December 1982 -

Article

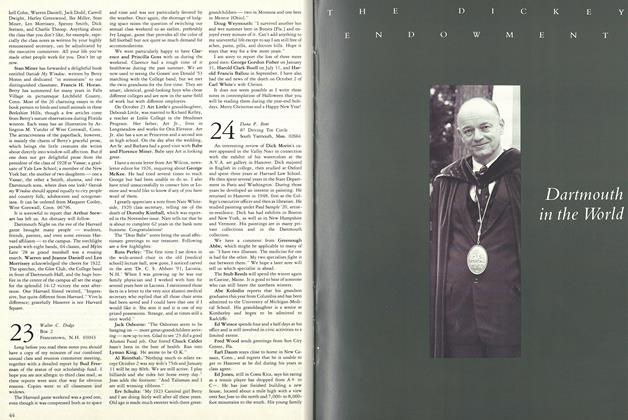

ArticleTHE DICKEY ENDOWMENT

December 1982

Jean Hanff Korelitz '83

Article

-

Article

ArticleMasthead

December, 1914 -

Article

ArticleFraternity Reopening Set for March 1

January 1946 -

Article

Article96 Sons of Dartmouth Men in Freshman Glass

November 1954 -

Article

ArticleNEWS OF THE FACULTY

February 1940 By E. P. K. -

Article

ArticleFROM DONNE TO DRYDEN

January 1941 By Hewette E. Joyce -

Article

ArticleCOLLEGE REMINISCENCES*

August, 1914 By J.K. LORD