Robert W. Mitchell '32, editor of Vermont's major statewide daily, the Rutland Herald, has become interested in two fascinating characters connected with Dartmouth's early years. His informal research on them illuminates the intertwined histories of the College and the Green Mountain State. Following are his musings on Samson Occom and Lemuel Haynes:

These words are introduced with some com- ments about Samson Occom, who assuredly has a claim to fame in Dartmouth annals. Witness the extensive use of his name in Hanover during the past two centuries.

My own contact with Occom occurred sever- al years ago when I attended a house sale in East Poultney, a community a few miles west of Rutland. After examining some old tools which were the reason for my interest in the sale, I turned around to look at a pile of old books on a card table. The signature in one of the books was a familiar one. It was the handwriting of Lemuel Haynes, the first ordained black clergy- man in the United States, who had served the first Congregational Church in Rutland for 30 years during the 1788—1818 period.

It turned out that the books were all from the library of Lemuel Haynes. And, according to a notation on the flyleaf, one of them had been acquired from Samson the Dartmouth Indian who had played such an important role in the early history of the College.

A connection between Occom and Haynes was of interest because one of the bits of uncon- firmed information in the biography of Haynes was that he had been offered a college education at Dartmouth. If it was ever offered, the oppor- tunity was not accepted, although Haynes later was granted an honorary degree by Middlebury College, the first black to be honored in that manner.

It was at about the time that the Haynes library books were discovered in East Poultney that Helen Mac Lam, selection officer at Baker Library, set out to learn whether there was any basis for the report that Dartmouth had offered Haynes a college education. Her findings were published in Baker's "Library Bulletin" in No- vember 1976. Her conclusion was that "the question of a relationship between Haynes and the College remains unresolved." However, she did report that Occom recorded in his diary having lodged overnight with Haynes while on a missionary tour. He may have presented Haynes with a book for his library at that time.

The results of Helen Mac Lam's extensive re- search were disappointing in another respect. "I had wanted Haynes to be a black activist, a hero in modern terms. Instead, he was a different kind of hero: a man who overcame great envi- ronmental obstacles through intelligence, per- serverance, and faith."

It wasn't until this year that she learned about Haynes what she had wanted to find out seven years before. A previously unknown manuscript bringing to light "the submerged evidence of Haynes's antislavery ideology" was discovered in Houghton Library at Harvard by Ruth Bogin, a member of the Department of History at Pace University. An article about her discovery and the text of the Haynes manu- script appeared in the January issue of The Wil-liam and Mary Quarterly. The manuscript was described as 46 small pages, measuring three and three-quarters by six inches, "clearly in- tended for publication," in which he called slavery "an offense against God" and "a vile and atrocious" practice.

Earlier writers studying Haynes, like Helen Mac Lam, had been disappointed that there wasn't more evidence of Haynes speaking out on the slavery issue.

Not that slavery was an issue in Vermont, which had become the first state, in 1777, to outlaw slavery and which had an exceedingly sparse black population. One reason Haynes left Massachusetts for a pulpit in Vermont in 1788 may have been its constitutional provi- sion against slavery. And he may have deemed it a waste of rhetoric to inveigh against an insti- tution that had been illegal for more than ten years in a state with only a scattering of blacks.

My own interest in Haynes was piqued when I was asked to be the speaker at the bicentennial of the church in West Rutland where he preached for 30 years. All the attention on the part of church members who planned the obser- vance was devoted to the church's first minis- ter, Benjiah Roots. Virtually no mention was made of Haynes, who was the second minister of the church and much more widely known in New England. His racial origin (he was the illegitimate son of a black father and a white mother) seemed to account for the lack of inter- est in celebrating his service to the church.

It was left to a church in South Granville, N.Y., where Haynes passed his declining years, to do him the honor he deserved, thanks in large measure to the interest of Dr. Paul Douglas of West Pawlet, Vt., a lawyer-clergy" man who served many years as president o American University in Washington, D.C. _ _ . -

On July 20, 1980, a ceremony was held at the Congregational Church of South Granville identifying Haynes's home there as a "nations historic landmark of significance in the histor) of the United States of America." David an Helen Mac Lam were there, and it was my prlU lege to be the speaker on that occasion an w help repair in some measure the omission in West Rutland observance.

Pictured above is Samson Occom and below,Lemuel Haynes both figures involved inDartmouth's early history.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe View from the Women's Locker Room

June 1983 By Agnes Kurtz -

Feature

FeatureHigh Tech Crisis

June 1983 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

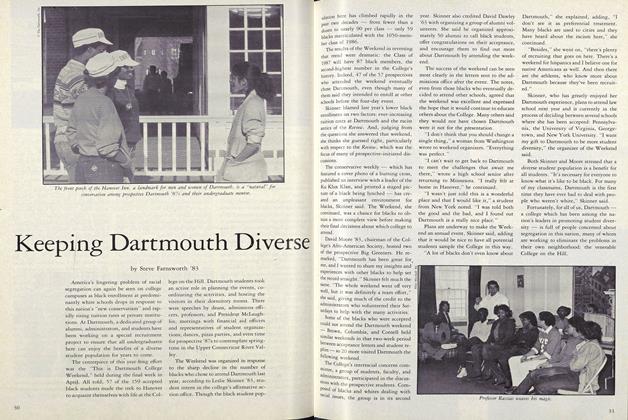

FeatureKeeping Dartmouth Diverse

June 1983 By Steve Farnsworth '83 -

Feature

FeatureJustifiable Pesticide

June 1983 By Robert Bell '67 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryIn Ledyard's Wake

June 1983 By Jean Hanff Korelitz '83 -

Feature

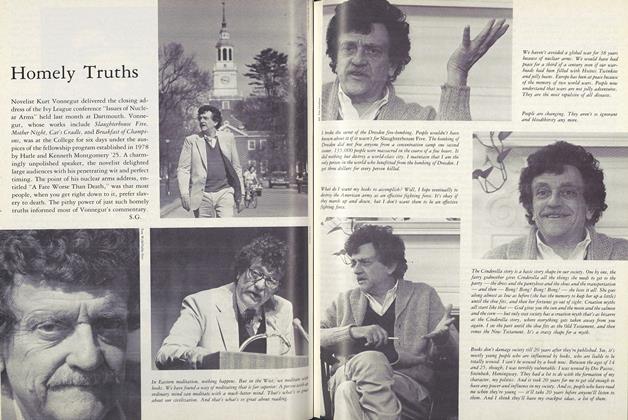

FeatureHomely Truths

June 1983 By S.G.