An Honor, To a Degree

In awarding honorary degrees, universities reveal their own essential values.

Sept/Oct 2002 JAMES O. FREEDMANIn awarding honorary degrees, universities reveal their own essential values.

Sept/Oct 2002 JAMES O. FREEDMANIN AWARDING HONORARY DEGREES, UNIVERSITIES REVEAL THEIR OWN ESSENTIAL VALUES.

CEREMONIAL OCCASIONS PROVIDE college presidents with opportunities to emphasize an institutions values, and no occasions are more potent than commencement ceremonies. In bestowing an honorary degree, a university makes an explicit statement to its students and the world about the qualities of character and attainment it admires most. Thus, the annual ritual is a practice rich in opportunity but it is also ripe for abuse.

Honorary degrees have been awarded in the United States from an early date. Some say the first was given in 1692, when Harvard University conferred the degree of doctor of sacred theology upon its own president, Increase Mather. Others cite 1753, when Harvard awarded an honorary masters degree to Benjamin Franklin for "his great improvements in Philosophic Learning, particularly with Respect to Electricity."

Although no reliable count exists, in the aggregate several thousand honorary degrees are conferred every year by the nation's more than 3,000 colleges and universities. In 11 years as president of Dartmouth College, I had the opportunity to hold up to the graduating students and our commencement guests the lives of more than 90 men and women worthy of emulation, a living tableau of persons from different walks of life, different areas of genius and accomplishment. In choosing honorees, I emphasized intellectual distinction and public service. If Dartmouth was to confer honorary degrees at all, I believed, the reason had to be to celebrate distinguished and sublime achievement.

Few would deny, however, that at some universities political considerations sometimes influence the selection (or nonselection) of honorary-degree recipients. In 1959 Harvard's president, Nathan M. Pusey, received a letter from two eminent members of his faculty, Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. and John Kenneth Galbraith, calling his attention "to the continuing preference for members of the Republican Party and the near exclusion from such honors of liberal Democrats." The letter went on: "We note with equal concern the virtually total exclusion of labor leaders."

As Schlesinger and Galbraith suggested, the conferring of honorary degrees has always been one of the ways in which the establishment honors its own. The practice often seems to follow party lines. Brandeis University has, for example, awarded numerous honorary degrees to prime ministers of Israel who were members of the Labor Party; it has yet, to my knowledge, to honor a prime minister who was a member of the Likud.

There are, as one might expect, conspicuous instances of omission quite aside from political considerations. A few years before William Faulkner received the Nobel Prize in Literature, the University of Mississippi voted against awarding him an honorary degree. Even after Faulkner received the Nobel Prize, the university never corrected the rejection.

Until recent decades, men were the overwhelming, if not exclusive, recipients. Only in 1922 did Dartmouth award its first honorary degree to a woman, the novelist Dorothy Canfield Fisher. Harvard was even slower: The first woman to receive its honorary degree was Helen Keller in 1955. During the 19th century, most honorary-degree recipients were Protestant, including many clergymen. Religious restrictions have long since disappeared, but the median age of honorary-degree recipients remains high, probably more than 60 years old.

Another practice devalues honorary degrees—and our ideals. Some institutions, on occasion, have engaged in the mass awarding of degrees as a means of celebrating an anniversary and augmenting its pomp and ceremony. Princeton University conferred 81 honorary degrees to mark its 150 th anniversary in 1896; Columbia University, in 1929, while commemorating the 175 th anniversary of the granting of the original charter to Kings College, named 134 honorees. British historian and statesman James Bryce may have had such ceremonies in mind when he tartly observed, in The American Commonwealth (1888), that honorary degrees are sometimes awarded "with a profuseness which seems to argue an exaggerated appreciation of inconspicuous merit."

But not every potential recipient is interested in receiving an honorary degree, creating an occasion for much embarrassment. In 1936, George Bernard Shaw made it amply clear that he did not wish to be honored at Harvard's 300th anniversary celebration. To an alumnus who proposed his name, Shaw replied: "If Harvard would celebrate its 300th anniversary by burning itself to the ground and sowing its site with salt, the ceremony would give me the greatest satisfaction as an example to all the other famous old corrupters of youth, including Yale, Oxford, Cambridge, the Sorbonne, etc., etc., etc."

Conversely, over the years certain individuals have not been shy about suggesting themselves for honorary degrees. In 1773, when Dartmouth was four years old, one Oliver Whipple of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, wrote to the College's founder and first president, Eleazar Wheelock, requesting "the favor" of an honorary degree, noting that he already held a masters degree from the University of Cambridge and "would gladly become an adopted Son of Yours." No record of the presidents response exists, but Whipple did eventually receive a degree. In the course of my presidential years in Hanover, I heard periodically from several persons, including one alumnus who had written several books and served as the president of three universities. Year after year, he brazenly approached me with requests for a degree, always supplying an exhaustive resume and fistfuls of adulatory articles. He never was honored.

Honorary degrees are, or course, one of the ways in which universities advertise themselves. Most announce the names of their honorees well in advance of commencement to generate favorable publicity. But the practice can backfire. From time to time, controversies have erupted among faculty members or students (sometimes both) when the names of prospective honorary-degree recipients have been made or become public before the ceremony. A celebrated example involved Oxford University's proposal, in 1985, to award an honorary degree to its alumna Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. After much contention centering upon her government's parsimony in the financing of higher education and scientific research, the university faculty turned down the proposal by a vote of 738 to 319.

Sometimes, too, campus controversy leads a prospective honoree to withdraw. The novelist Anna Quindlen backed out of a commitment to a prominent Roman Catholic university after she foresaw that the church hierarchy, when it realized that she held a pro-choice position on abortion, would eventually cancel the invitation. Indeed, in 1990 the Vatican blocked the University of Fribourg, in Switzerland, from honoring Archbishop Rembert Weakland of Milwaukee; his statements on abortion, the Vatican said, had caused "a great deal of confusion among the faithful."

In 1986, Drew Lewis, the former secretary of transportation, stunned the commencement audience at Haverford College, a Quaker institution, by ripping off his ceremonial hood and declining the honorary degree just bestowed upon him. He acted upon learning that there had been substantial faculty and student opposition to the award because of his role in responding to a controversial strike by air-traffic controllers. He told the audience that he came from a Quaker background and shared the denominations strong belief in the principle of consensus. "There is no consensus on this degree when one-third of your faculty object," he said.

The original purpose of honoring distinguished personal achievement has also been widely modified—some would say blighted—by institutional desires to flatter generous donors and prospective benefactors to whom more relaxed standards (typically pecuniary) are often applied, (indeed, some wags have argued that such degeneration into a quid pro quo style enables a college "to get rich by degrees.") Similarly, any aspiration to populate an American peerage is surely trivialized by decisions to garner a fleeting moment of public attention by awarding an institutions ultimate accolade to mere celebrities who are often famous principally for being famous.

Among any institutions list of honoraiy-degree recipients, there are bound to be curiosities. For reasons now obscure, Dartmouth has conferred honorary doctorates twice upon two of its alumni: Robert Frost (in 1933 and 1955) and Nelson Rockefeller (in 1957 and 1969). Many institutions have realized that husbands and wives make a fetching combination for degree-granting occasions. Among the most popular in that category have been Hume Cronyn and Jessica Tandy, Melvyn Douglas and Helen Gahagan Douglas, and Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne.

On the plus side, public officials who have a moral dimension to their character are especially prized because they are thought likely to use the occasion of being a commencement speaker to make an important public pronouncement. The model most cited is George C. Marshall, who, as secretary of state, proclaimed the Marshall Plan at Harvard's commencement in 1947. High on such lists in recent years have been Mikhail Gorbachev, Vaclav Havel, Nelson Mandela and Archbishop Desmond Tutu. (In an interview, Havel once said, "I was awarded honorary degrees at universities around the world, and at every one of those ceremonies I had to listen to the story of my life. And those biographies were always the same fairytale.") In recent years, African-American artists and scholars—especially Maya Angelou, John Hope Franklin, Henry Louis Gates Jr., Spike Lee, Toni Morrison, Alice Walker and Cornel Westhave also been popular.

Every president is conscious, at honorary-degree time, of being caught up in a prestige race with other colleges and universities. This is an age that commodifies fame. So intense is the competition that many colleges now pay some honorary-degree recipients, at rates that commonly exceed $l0,000, to lure them to deliver a commencement address. Dartmouth never did so during my 11 years there, and I know of no instance in its past. In paying an honorary-degree recipient to speak, a college seems to be acknowledging that it desires having the speakers services more than the speaker values having the colleges degree.

Moreover, despite all the effort that is devoted to selecting and then attracting honorary-degree recipients, there is little evidence that commencement speakers have more than a fleeting impact on their audience. Most adults, in my experience, cannot recall the speaker or the honorary recipients at their own commencement, probably because, in the excitement of the day, their thoughts were elsewhere.

Honorary degrees do serve at least one important purpose beyond suggesting role models to students and enhancing institutional prestige, however. They often, in my experience, forge enduring bonds of friendship and mutual regard between the college and the recipient. In the years that follow, honorees may be amenable to visits from students, providing summer jobs and career counseling, opening doors to professional opportunities, and offering personal encouragement. Often they return to the college to deliver speeches, appear at symposia, or meet with classes.

Perhaps the greatest risk is that a recipient will turn out, in retrospect, to have been ill-chosen. Ten universities—including Princeton, the University of Chicago and Brown University—conferred honorary degrees upon Count Johann-Heinrich von Bernstorff, the German ambassador to the United States before World War I; many institutions withdrew his degree after the war began, on the ground that, as one said, "He was guilty of conduct dishonorable alike in a gentleman and a diplomat."

Finally, a few words about honorary-degree citations. Such efforts are something of an art form unto themselves. Unfortunately, the crafting of elegant citations has fallen into considerable disuse. Too often presidents read citations that have been written by others—that is why they sometimes seem unfamiliar with the textand are prolix, cliched and embarrassingly fulsome. Although I always wrote my own citations, I now see that I, too, may sometimes have been guilty of lapsing into excessive adulation. For example, I saluted Maurice Sendak, the author of classic children's books, as one whose "claim upon a generation of readers has been so great that, among members of this graduating class, you may well be the single most widely read author." Although the graduates applauded enthusiastically, I promptly heard from indignant friends and admirers of Theodor S. Geisel '25 who, as Dr. Seuss, was the author of more than a few books widely popular with the graduating generation.

Despite the problems, however, on balance the practice of awarding honorary degrees strikes me as salutary. For all the occasional abuses, frivolities, incongruities and howlers, there are still too few opportunities in our society for recognition of men and women who have made contributions of genuine significance. If universities honor such people, they also honor their own essential values. When I was president of the University of lowa, I always regretted that we did not award honorary degrees, because of faculty hesitation. Even though I appreciated the concern that political influence might trivialize the process, I believed that we missed an important opportunity.

When conferring honorary degrees at Dartmouth, I hoped to persuade our students and commencement guests that the character and attainment of those we were honoring were worthy of emulation and admiration. So long as every recipient meets that mark, a college is entitled to believe that the public ritual of awarding degrees addresses sacred matters and illuminates the relevance of a liberal education to the lives of men and women.

"Every president is conscious, at honorary-degree time,of being caught up in a prestige race with other colleges and universities.This is an age that commodifies fame."

JAMES O. FREEDMAN is president emeritus of Dartmouth College andof the University of Iowa. A longer version of this essay will appear in Liberal Education and the Public Interest; to be published by the University oflowa Press early next year.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

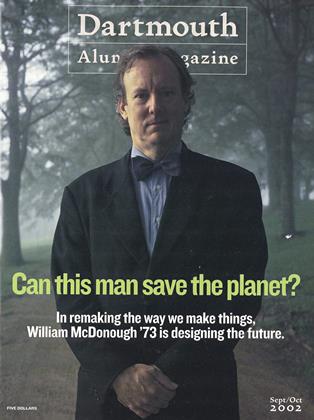

Cover Story

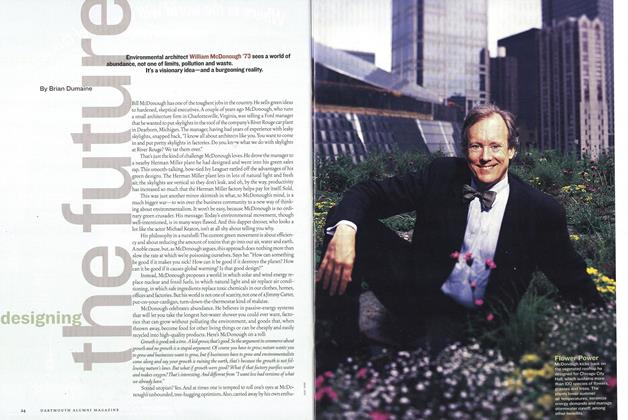

Cover StoryDesigning the Future

September | October 2002 By Brian Dumaine -

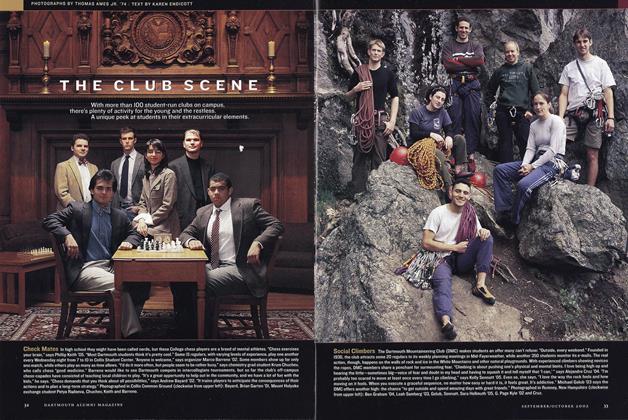

Feature

FeatureThe Club Scene

September | October 2002 -

Article

ArticleSeen & Heard

September | October 2002 -

Personal History

Personal HistoryRiver Dance

September | October 2002 By Jonathan Agronsky ’68 -

Article

ArticleAcademic Aesthetics

September | October 2002 By President James Wright -

Class Notes

Class Notes1997

September | October 2002 By Abby Klingbeil

JAMES O. FREEDMAN

-

Article

ArticleTHE PASSIONS OF SCIENCE

December 1990 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleLessons of the Law

NOVEMBER 1992 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleNothing Less Than a Hero

April 1993 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleObligations of the Educated

September 1995 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleThe Education Gap

January 1996 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleInfluential Minds

May 1998 By James O. Freedman

Features

-

Feature

FeatureNous Étudiants à l'Étranger

FEBRUARY 1967 -

Feature

FeatureInternational Catalyst

FEBRUARY 1967 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryNick Lowery '78

March 1993 -

Feature

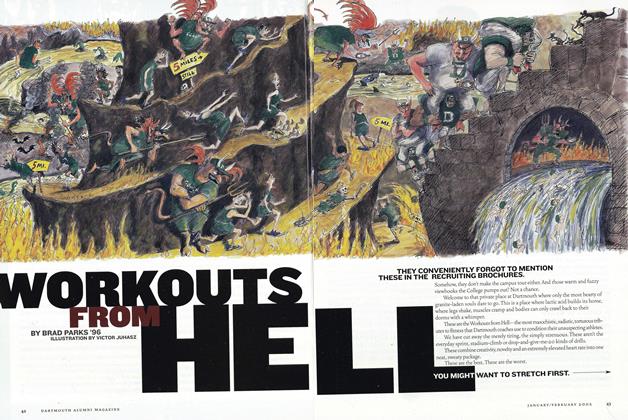

FeatureWorkouts From Hell

Jan/Feb 2002 By BRAD PARKS ’96 -

Feature

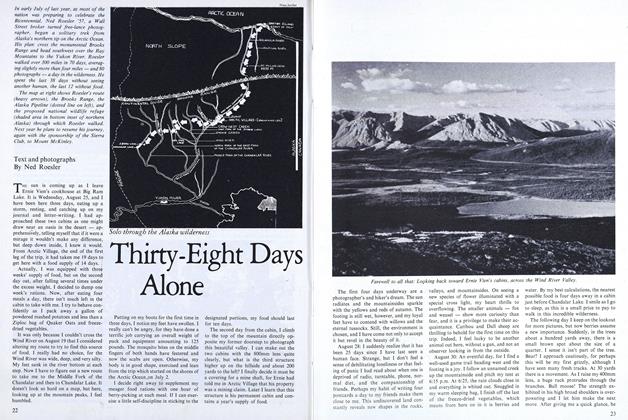

FeatureThirty-Eight Days Alone

SEPT. 1977 By Ned Roesler -

Feature

FeatureWORLD UNDERSTANDING: A Job for Mass Communications

OCTOBER 1966 By WALTER WANGER '15