The Team Canada veteran, born into a legendary hockey family, can’t imagine going through life without goals.

Midway through an exhibition game on a Thursday night in September, at the nearly empty WinSport Olympic training complex in Calgary, Alberta, Gillian Apps followed a rush up the ice from her familiar spot out on the left wing and slipped into an open space on the near side of the net. Using her long reach she gathered a loose puck and swept across the crease. The goalie, a 17-year-old on one of Calgary’s elite AAA men’s development teams, was caught out of position and frantically shifted to catch up with her. Apps held her course a fraction of a second longer, forcing the goalie to commit. She dipped her front shoulder to cock the lever on a wicked backhand shot—then slid the puck back across the crease to her streaking veteran teammate Hayley Wickenheiser, who buried it in the half-empty net.

The goal, in itself, was unremarkable. The Canadian women’s team long ago established a level of play that is dominant on the world stage, winning 10 of the past 14 world championships and gold medals at the past three Olympics. Today the women had already finished off several crisp sequences that would blur together with countless other well-executed plays on the way to a 7-2 thrashing of the U-18 Calgary Northstars. In the official Team Canada write-up of the game the following day, the Wickenheiser goal at 10:09 of the second period would warrant barely a mention.

For Apps, fighting for a spot on the Olympic roster, those few seconds stood out as symbolic. Once a rising teen star in Canada’s centralized Olympic training camp, Apps was now almost 30 years old—and a two-time gold medal winner. At the 2006 Games in Turin, Italy, she had been the third-highest scorer among all players. She is still a big power forward—at 6 feet tall and 175 pounds, the biggest player on the squad—and still plays the game with what one Canadian sports writer called “controlled recklessness.” But as a veteran her role has evolved. She is now looked to for intelligent, disciplined hockey at both ends of the rink, to forecheck, use her size to control the ice, dig loose pucks out of corners, fight for position in front of the opponent’s net, kill penalties and create opportunities for her teammates. She is one of 13 returning players from the Vancouver gold-medal team, all of them being pushed by an up-and-coming generation that’s faster, better trained and more skilled. With 27 roster spots getting trimmed to 21 by the end of December, none of the veterans’ positions were safe. On that Thursday night in Calgary, Apps’ 21-year-old linemate, Mélodie Daoust, scored two of the team’s seven goals. Apps’ contribution couldn’t be measured by statistics.

After the game she spun her legs for 15 minutes on a stationary bike, drank an energy drink and showered. Two months into the training camp she was feeling the grind of the six-day-a-week conditioning, the push of the 50-game exhibition schedule. Her body felt tired, but strong. “As you get older you need to train harder,” says Apps. “It’s really hard to tell where you stand. There are always younger players trying to take your spot. I’d say I’m not as secure right now as I was when I was 24 years old, but it all depends. Roles change. You just adapt to those changes.”

The fitness and strength of the younger players has forced Apps to become not just a better hockey player but a better athlete. She had added cycling and other cross-training to her year-round regimen. (In a 2010 Nike television ad Apps appears straining through a wind sprint, pulling the resistance of a speed chute behind her. Looking straight into the camera, catching her breath, she says, “Destiny doesn’t push this hard.”) The night of the exhibition game in Calgary she fell into bed after midnight in a modest furnished house five minutes from the training complex and rose at 7:30 the next morning, ready do it all over again.

The camp had reached the point where the coaches were experimenting with different lineups on the ice, trying to get at the intangible sense of a team’s chemistry. Dan Church, the new head coach, was relying on Apps as part of an informal “leadership group” of older players to serve as a bridge between the team and the coaching staff. He appreciated the way that Apps had embraced her changing role, the unusual combination of discipline and joy she brought to the game and her willingness to mentor younger players. For Church, there was more there, too, that was harder to put into words. He was once asked if something distinctive marked the hockey players who came out of the Ivy League. “Yes,” he said. “But not in the way they play. It’s something you see off the ice.”

Apps brings a lineage to the team that goes deeper than Dartmouth. Her father, Syl Apps Jr., was an all-star player in the National Hockey League. Her grandfather, Syl Apps Sr., was a three-time Stanley Cup winner with the Toronto Maple Leafs and a pole vaulter at the 1936 summer Olympic Games in Berlin, Germany. She has a cousin who rowed in two Olympics. Her older sister played for a decade on the Canadian national soccer team before retiring, and her older brother skated for Princeton and spent four years in minor league hockey before pursuing a master’s degree.

Apps’ champion bloodlines compensated for her late start in the sport, which she picked up casually at the age of 12. “When I was working hard to make the national team I didn’t consciously think of my hockey as being part of a legacy,” she says. “Now that I’ve competed in the Olympics I feel honored to have contributed to the family tradition.”

Now she’s reached the age where it’s natural to start thinking about what might come after hockey. “I’m intrigued by the idea of getting an M.B.A. and seeing where that might lead,” she says when pushed about her future plans. “But right now I’m not thinking about anything except making this team and getting to Sochi.”

The grueling Olympic training camp came at a personal cost. Of the 27 women in Calgary, all but six had relocated from outside of Alberta. They’d put school or careers on hold and left behind homes, friends, husbands (only a couple of her teammates had married because the lifestyle discourages long-term relationships). They did it for low pay and Spartan living conditions, for the love of the game and for a kind of fame that spreads fleetingly into households across North America once every four years, then settles back into hockey camps and academies and cold ice rinks where young girls dream of Olympic gold.

With the retirement of teammate Cherie Piper ’06, Apps—if she makes it to Sochi—will carry the torch as Dartmouth’s lone representative in ice hockey, keeping alive a tradition that began with the introduction of the women’s event in the 1998 Nagano Games. There’s another Dartmouth player coming up behind her in the pipeline: Laura Stacey ’16, a highly touted member of Team Canada’s U-22 team. “I’ve been texting her a lot,” says Apps, who is savoring the competition and whose age in 2018 (35) wouldn’t automatically rule out a fourth Olympic attempt. “I’m keeping tabs on her.”

“ITALY WAS SPECIAL BECAUSE IT WAS MY FIRST TIME. THEN IN VANCOUVER WE GOT TO DEFEND OUR GOLD MEDAL ON OUR HOME ICE. RUSSIA WILL BE EXCITING BECAUSE IT'S SUCH A DIFFERENT CULTURE. NO TWO OLYMPICS ARE THE SAME." GILLIAN APPS

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

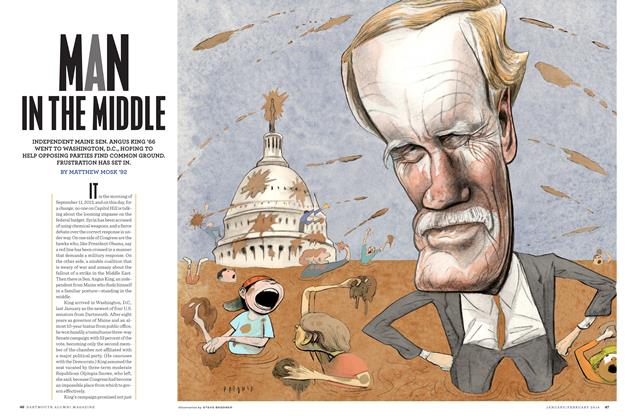

FeatureMan in the Middle

January | February 2014 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

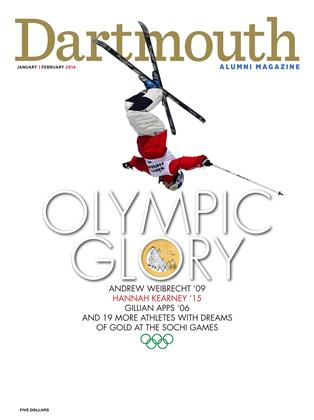

Cover Story

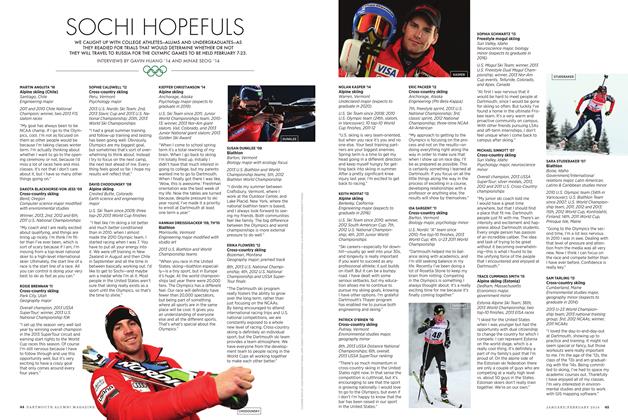

Cover StorySOCHI HOPEFULS

January | February 2014 By Gavin Huang '14, Minae Seog '14 -

COVER STORY

COVER STORYThe Contenders

January | February 2014 By BILL GIFFORD ’88 -

Feature

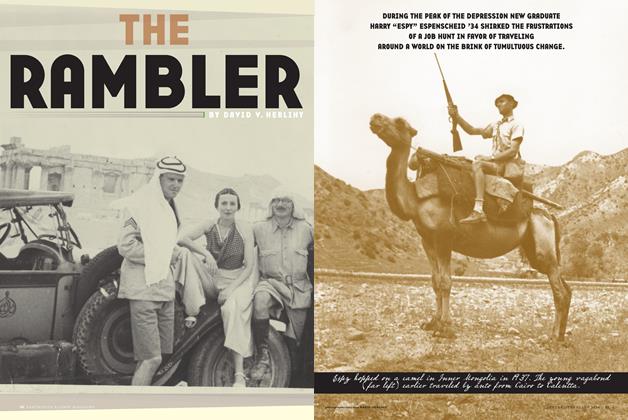

FeatureThe Rambler

January | February 2014 By DAVID V. HERLIHY -

Cover Story

Cover StoryANDREW WEIBRECHT '09

January | February 2014 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDEHow the West Was Fun

January | February 2014 By ALEXIS C. JOLLY ’05

JIM COLLINS '84

-

Feature

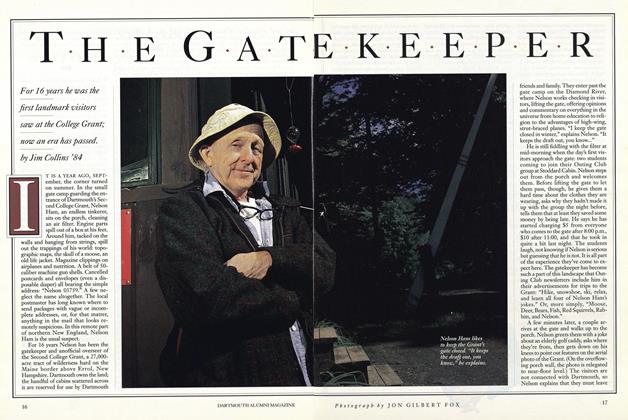

FeatureThe Gate keeper

SEPTEMBER 1991 By Jim Collins '84 -

Feature

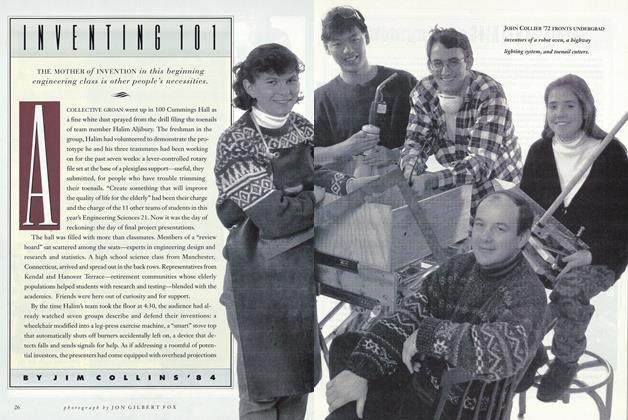

FeatureINVENTING 101

MAY 1992 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

Feature

FeatureFloating Home

June 1992 By Jim Collins '84 -

Feature

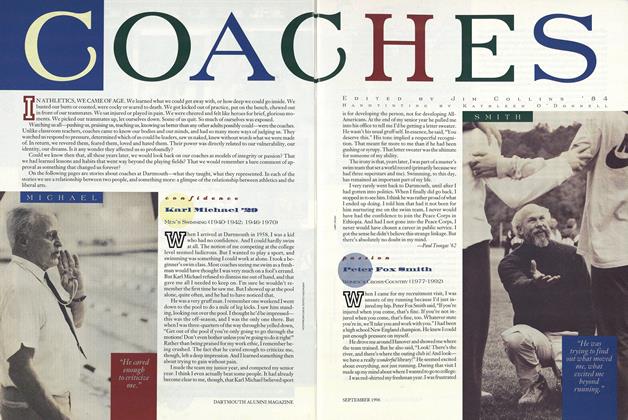

FeatureCOACHES

SEPTEMBER 1996 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

Article

ArticleThe Role of an Intellectual

JANUARY 1998 By Jim Collins '84 -

Feature

FeatureOn The Water

Jul/Aug 2004 By JIM COLLINS '84

Features

-

Feature

FeatureNatural Energy Resource

May 1977 -

Feature

FeatureMt. McKinley Conquered

NOVEMBER 1967 By Anthony H. Horan '61 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO BECOME A LAWYER

Sept/Oct 2001 By DANIEL WEBSTER -

Feature

FeatureThe Antileadership Vaccine

FEBRUARY 1966 By JOHN W. GARDNER -

FEATURE

FEATUREIdeal Exposure

MAY | JUNE 2019 By STEVE GLEYDURA