Senior Matt Mcllwain has hundreds of alumni going through college again for a much lower price.

RESUME—MATTHEW S. McILWAIN Creator and President, Dartmouth. Graduate Game Cos. Created games rules and designed game board. Raised over $12,000 in capital through business sponsorship. Coordinated subcontracting and production process between 8 different companies. Directed packaging and mail-order process. Marketed wholesale, direct sale and mail-order. Broke even after 6 weeks of sales on initial 2000 games. Currently designing franchise system for production at other colleges.

The way to win the Dartmouth Graduate Game is to graduate from the College. One does this by effectively employing what the game's inventor calls the "Prisoner's Dilemma," by stratagems such as taking one's professor to the Ivy Grill, and by enduring freshman dining, tuition payments, and a parent's visit.

"It's a small challenge," says the blurb on the game's box, "but there are those who love it."

The game's "Creator and President," Dartmouth student Matt McIlwain, is the first to admit that his invention does not imitate precisely the rigors of matriculating at the College. But Mcllwain has higher ambitions: "I wanted something that could be put under the Christmas tree to bring the College to the alumni in a positive light."

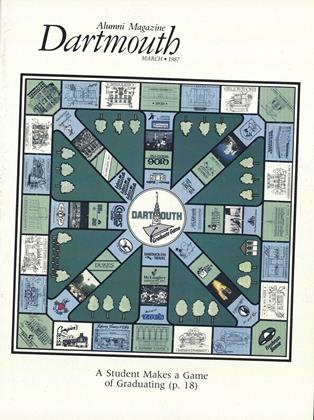

The result is a board designed around a rendering of the Hanover Green. Three to six players select majors and roll dice to make their way around the Green, starting at a space marked "Freshman Beanie." Credit is earned and lost through "extracurricular" and "academic" cards, which (to the probable chagrin of Dartmouth parents) are given equal weight.

The game's originality and possible application to other schools have attracted extensive media coverage, including the Associated Press, local television, the Boston Globe, and USAToday. While he has won some measure of fame, however, Mcllwain has yet to gain his fortune. "So far I've netted about $3,000," he says. "But to earn that, I worked 70 hours a week for ten weeks.

"It wasn't my goal to make money' he adds. At least, that is not is goal in the short run. But last January, McIlwain was one of the few students who seemed to be thoroughly enjoying corporate recruitment. Even while attending high school in Miami, he participated in Junior Achievement, an organization that helps students start amateur businesses. While Mcllwain's "company" made picture frames, a rival group put together a Monopolylike game in which local businesses paid for spaces on the board. The point wasn't lost on Mcllwain.

The idea for a Dartmouth game came to him freshman year. It wasn't an original thought. A board game for Stanford already existed. The University of Michigan has a game called Michiganopoly, and Harvard was preparing a game to help celebrate its 350 th anniversary.

Mcllwain had little time to follow up on a Dartmouth game, however. He went on to major in government and economics while playing varsity soccer, coaching junior varsity soccer, helping out in the Big Brother/Big Sister Program, serving as co-leader of Athletes in Action, an adjunct of the Campus Crusade for Christ; and holding such campus posts as chairman of the Student Assembly Social Council, chairman of Carnival on the Green, and publicity chair of the Dartmouth Entrepreneurs Club.

Nonetheless, he didn't stop thinking about the game. One night, in the winter of 1985, Mcllwain came home from his semester's job as an assistant for a large Washington, D.C., law firm, "and the whole thing came to me," he says. He grabbed a legal pad and began a list of tasks. Typically, the business details came first: "A. Get a post office box. B. Find a printer. C. Invent a game." He set a goal for himself to have the game on the market by Dartmouth Night, 1986.

That summer, while holding parttime jobs at the Hanover Inn and at Collis Student Center, he began work on the game's rules and came up with a prototype. The core of his idea was "game theory," a concept he learned in his sophomore year. (See the sidebar on page 21.) "The idea was the easy part," says Mcllwain. "The hard part was producing the game and selling it."

Like any good businessman, he chose as his first step to make as many contacts as possible. He touched bases with Dean of the College Edward Shanahan. He went to Sean Gorman, the assistant College counsel, who explained legal issues such as copyrights and advertising agreements. Gorman also briefed Mcllwain on the College's licensing agreement which, in exchange for use of the Dartmouth name, requires a licensee to give the College 6 percent of the gross. Mcllwain also went to Matt Marshall, manager of the Hanover Inn. "I asked him for more than advice," Mcllwain says. "I also asked him to help sponsor the game."

Dartmouth junior John Sipple provided Mcllwain with photographs of campus scenes for use in making the board. Peter Blum 'B7 did architectural drawings of buildings on campus. An area designer, Stella Rhinehard, agreed to take on the graphic chores. During one weekend's intensive work, she did sketches and convinced Mcl lwain change the rules to allow for a simplified design.

That summer he shared a house on West Wheelock called the Blue Zoo with some medical students. In a single long night, his housemates helped him come up with most of the ideas for the game's "Academic" and "Extracurricular" cards. They laced the cards with vintage undergraduate hum or. "Lost your shorts at the rope swing," says one card. "Lose 1 distributive credit, too." Another card tells the player he has just eaten a whole pint of ice cream. "Roll again," it admonishes. "You need the exercise."

Armed with a mockup of the game, Mcllwain took it to various Hanover businesses. The charge for a space on the board varied between $200 and $600, depending on the space's prominence. The Hanover Inn was among the first customers, taking out a space for itself and for the Ivy Grill. "I had worked there, and that was key," Mcllwain says. Other businesses followed suit, and within two weeks he sold every space on the board.

Among his customers was the Dartmouth Bookstore, whose managers suggested what the game industry calls an "adult box"—a square shape the size of Trivial Pursuit. For that, Mcllwain went to a box maker in Maine. The College's print shop contracted to do the cards, pads, and rules, which Mcllwain designed on his Macintosh computer. A company in New York made the game pieces. A Hanover printer made the full-color game sheets, which a firm in Long Island laminated onto boards. The parts were assembled and shipped by a company in New Hampshire in the fall of '86, just in time for the Harvard football game. During the first month, of the 2,000 games he had produced, local stores and Mcllwain himself sold 400.

But when all the hours he spent on his invention are totalled, Mcllwain's profits (the retail price is $14.95) have earned him a tad over the hourly minimum wage—so far. The games are still selling, he points out, and, "if business continues as phenomenally as it has," he says, he may produce more.

Although Mcllwain appears sincere in his noble motives for the game, its makeup has a decided commercial cast. Paid spaces on the board trumpet such venerable businesses as Cam- pion's and Lou's alongside relative newcomers such as Molly's Balloon and Hanover Hot Tubs. Mcllwain clearly bent over backward, to the point of toppling, in his effort to satisfy these customers. One "Academic Card" reads: "Eastman's pharmacy proved they were worth the walk when they had the right cough medicine you needed to concentrate on exams. Earn 1 major credit."

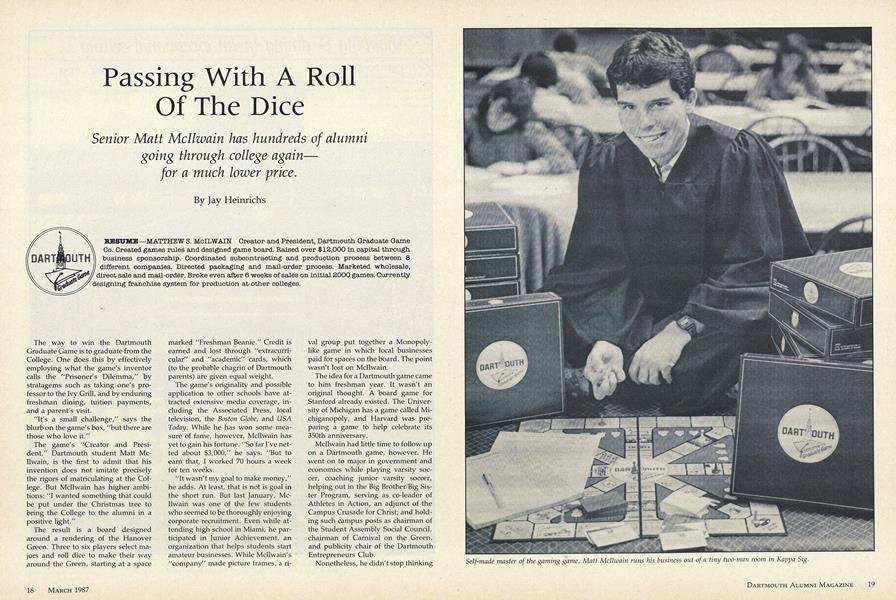

Like many business-minded students who go through Corporate Recruiting, Mcllwain has an answering machine. Its message grandly refers to his tiny two-man room at Kappa Sigma Gamma as "the office of the Dartmouth Graduate Game." Recently, he invited an Alumni Magazine staffer to his room to participate in a game with fellow frat brothers. After turning up a dozen or so cards touting Hanover businesses, one player lost his shorts on the rope swing. "Did the swing pay for this card?" he asked sarcastically. Mcllwain smiled.

Several cards game offer the opportunity to ask a trivia question of another player. "In what year did the College sell its cog railroad?" this writer asked, choosing not to reveal his ignorance of the answer. No one else knew, either. Another player asked his frat brother the heights of the figures on the Baker weather vane. His answer was correct for three of the four objects, but he failed with the Indian.

"The best part of the game is that it sparks conversation," McIlwain said as he sipped a beer and contemplated a matrix card. "Someone will mention that he's going to Spain, and we'll all talk about language studies, or a guy will draw a card with something about sports, and the other guy will say, 'Weren't you AllIvy?'"

Nonetheless, an older group—even one entirely composed of Dartmouth alums—might have a rougher time with the game and its cards. Amid road trips and Winter Carnival are references to "N.R.O.'s" and "Northern New England's hot FM Q106." In defense, Mcllwain pleads education: "The game helps alumni to find how the College is changing. It also helps parents relate to the students. Besides, you don't have to be an expert in today's Dartmouth to win." As vivid proof, the night he played the game with the Alumni Magazine writer and three frat brothers, Mcllwain came in last. "I've been playing this game ever since I invented it, and I've lost every time," he complained.

But Mcllwain was not all that downtrodden. He had already set his sights on a much bigger game: as of late January, three corporations had called him back for a second job interview.

Self-made master of the gaming game, Matt Mcllwain runs his business out of a tiny two man room in Kappa Sig

DARTMIUTH

"The idea was the easy part.The hard part was producingthe game and selling it."

Jay Heinrichs is the editor of this magazine.While playing the Dartmouth GraduateGame, he came in just ahead of Mcllwain.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature"These Children Are the Future"

March 1987 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureThe Magic Bullet

March 1987 By B.J. Schulz arid Mary McFadden -

Feature

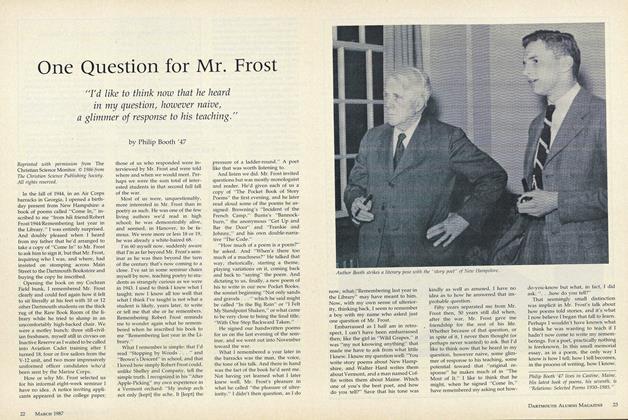

FeatureOne Question for Mr. Frost

March 1987 By Philip Booth '47 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

March 1987 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1983

March 1987 By Ken Johnson -

Article

ArticleSenior Epiphany

March 1987 By Lesley Barnes '87

Jay Heinrichs

-

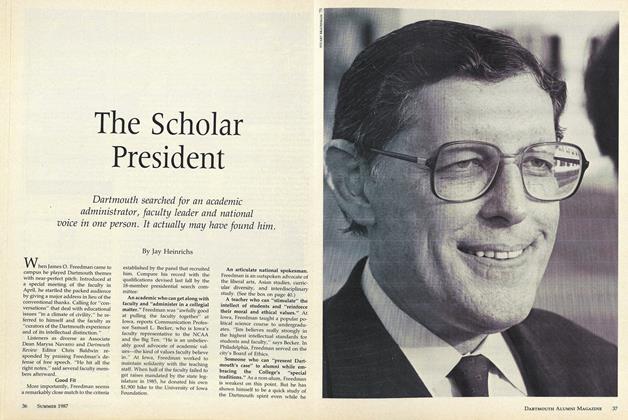

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Scholar President

June 1987 By Jay Heinrichs -

Article

ArticleThe Dean Of Spin

OCTOBER 1990 By Jay Heinrichs -

Cover Story

Cover StoryChoices

September 1992 By Jay Heinrichs -

Article

ArticleA Book for Lovers of the Raucous Side of Dartmouth

May 1994 By Jay Heinrichs -

Article

ArticleYour Breath Smells So Bad People on the Phone Hang Up.

November 1994 By Jay Heinrichs -

Article

ArticleNels Comes Home

April 1995 By Jay Heinrichs

Features

-

Feature

FeatureM.S. Candidate

MARCH 1967 -

Feature

FeatureAn Irresistible Force?

September 1975 -

Feature

FeatureExit with a Flourish

June 1979 By Beverly Foster -

Cover Story

Cover StoryFresh Heirs

NOVEMBER 1989 By Heather Killerew '89 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO RUMBA

Sept/Oct 2001 By ROBERT TIRRELL '45 -

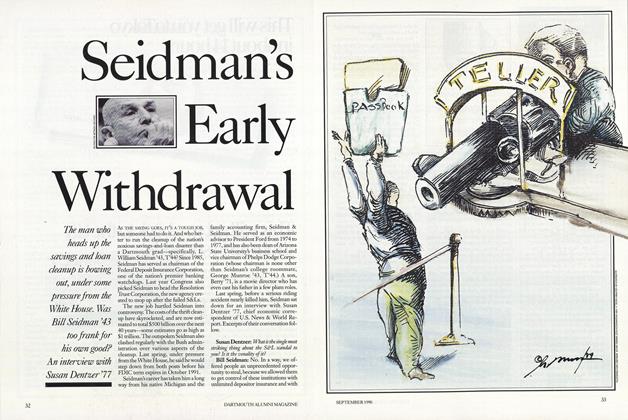

Feature

FeatureSeidman's Early Withdrawal

SEPTEMBER 1990 By Susan Dentzer '77