The best museums affect how we experience art.

What makes one art museum memorable, while others threaten us or make us feel merely dutiful? There is a school of thought that says museum architecture should be neutral, so as not to compete with the works of art. But stop for a moment and think about your actual responses to museum buildings.

A powerful architectural presence can open us up to new experiences by putting us in an extremely active state of mind. The best museums manage to convey the message that all this was done for us. Such a museum makes us feel that this place is special, and that therefore the things in it must be special and the people who come here must be special, too.

You can test this idea for yourself. For example, if you are in London with an afternoon to spare, you might go to the National Gallery. It's a great institution. But for me, those endless marble galleries, each filled with masterpieces, have a cumulative deadening effect on the brain. For contrast, I recommend a visit to Sir John Soane's Museum at Lincoln's Inn Fields near Holborn Station. An hour in the Soane Museum tiny and unchanging, even down to the ancient "guard" at the front doordoes my spirit more good than an entire day spent at the National Gallery. Designed, built, and inhabited by the very brilliant and very eccentric early nineteenth-century architect Sir John Soane, this building is unadulterated magic. A history of human form and symbol is compressed into tiny, stacked on each other rooms linked by a gravity-defying staircase.It's better than Disneyland.

Charles Moore, architect of Dartmouth's own Hood Museum, built on Soane's ideas. Moreover, Moore believes that the body reacts to its changing relationships with other physical objects within the spaces it inhabits that perception is a subiiminally tactile experience. Thus, the more changes provided in the environment, the more actively engaged the viewer will be. (If you want to explore this idea further, see Kent C.Bloomer and Charles W. Moore's Body, Memory, and Architecture, Yale University Press, 1977.)

Moore designed the entrance to the Hood with this in mind. You proceed up a wide ramp, enter through a multicolored rotunda, then turn to the suddenly vertical space of the lobby, where you have several choices of direction into the galleries, each of which feels and looks quite different from the others. As you ascend the airy staircase, daylight floods through lattice-like windows on your left and bounces off blue-green glass on your right between big concrete piers that start deep in the ground and end abruptly at the level of your shoulder when you reach the top step. The experience of light and the high view of the Green has almost, but not quite, prepared you for the vast nave of skylit space that welcomes you to the second floor. In such a small building, this is an amazing combination of events. Above all, it's a profoundly processional experience, like a ritual. And, like a ritual, it makes you feel that a special event is taking place: you're about to look at art.

Here is my short list of favorite museums with my quite personal reactions to them. Next time you visit a museum, be sensitive to your reactions and alert to what causes them. I believe you will find that the quality of the architecture contributes almost as much to your response as the virtues of the art you are viewing.

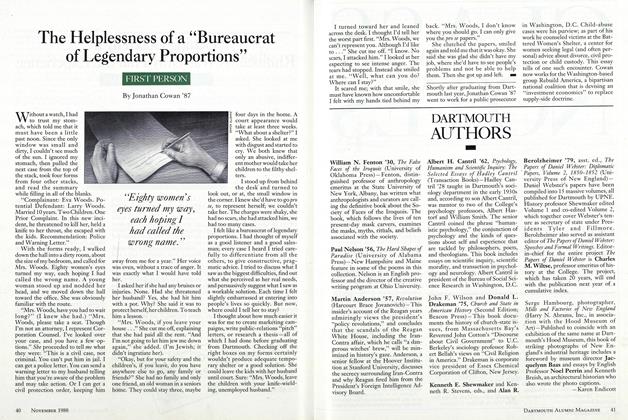

Jacquelynn Baas at the Hood.

Jacquelynn Baas doesn't mind being asked, "What is art?" Smiling, she readily replies: "Art is what artists make. If an artist says it's art, who am I to disagree?" That response may seem surprising, considering that it comes from the director of the Hood Museum of Art. But it is measuredly puckish, designed to call staid notions about art into question. "Art can challenge the idea tat the world has to be the way it is," Baas asserts. "Many people are defensive about works of art, and the more complex the piece is, the more defensive they are. Our goal in the museum is to make people feel welcome so they will let natural curiosity take over. "I like to watch people in the galleries to see their reactions. When they call friends over to look at something-especially one of the more puzzling works I consider that we've been successful." Baas, who helped to create the Hood, holds a doctorate in art history from the University of Michigan and has a background in administration. During undergraduate days at Michigan State she did art. "I gave up painting when I realized the world didn't need another mediocre painter," she laughs. "But I believe that experience in studio art gives museum directors a much-needed appreciation of what it is that artists do." Being director of the Hood requires Baas to reach beyond her own field of nineteenth-century French art. She considers this a perk of the job. Her favorite show at the Hood was the 1986-87 exhibition of prints by Edvard Munch, largely because it challenged her own sensibilities. "It was such a difficult task for me as a woman to deal with Munch's aggressive treatment of women," Baas explains. "You may not agree with an artist's politics or sexual politics, but if he's good, you can understand the work and become a more complex person." Baas's work for the Hood has attracted national attention. But this time Dartmouth's success is another's gain. At the end of fall term Baas leaves the College to become director of the University Art Museum at the University of California, Berkeley. Karen Endicott

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

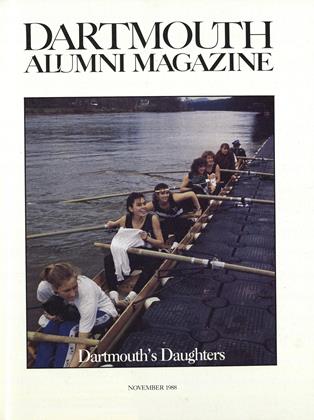

Cover StoryDaughters of Dartmouth

November 1988 By Anne Bagamery '78 -

Feature

FeatureGlory Days

November 1988 By Woody Klein '51 -

Feature

FeatureThe Helplessness of a "Bureaucrat of Legendary Proportions"

November 1988 By Jonathan Cowan '87 -

Feature

FeatureQuestion: What Professional School Gives Credit for Throwing Pies?

November 1988 By Steve Lough '87 -

Feature

FeatureGetting Gored by a Rhinoceros Was Only Half the Experience

November 1988 By Emily Hill '90 -

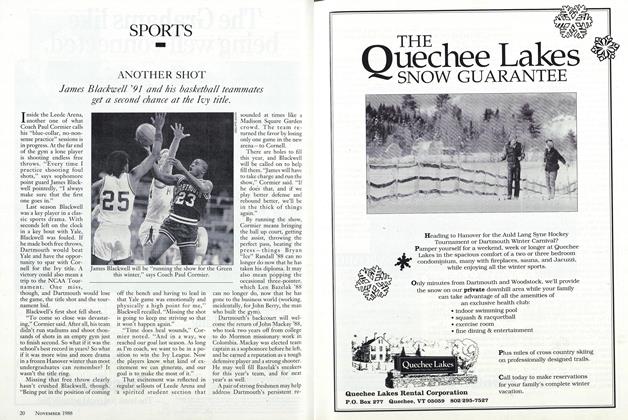

Sports

SportsANOTHER SHOT

November 1988