"Making monetary policy has to be at least as difficult as bringing up a teenager." Arnold Harberger, professor of economics at the University of Chicago, made this eloquent observation during a conference on alternative monetary policies held at Dartmouth in late August. Harberger's analogy, coming after ten hours of presentations and discussion, was greeted with tired laughter and nods of agreement from all.

Nearly 60 academics, businesspersons, and governmental representatives -all economics experts attended the conference to discuss alternate systems for managing the money of both this nation and the world.

"There is a considerable degree of interest in this idea among Washington policymakers," said Dartmouth Economics Professor Bill Dougan, who codirected the conference with colleague Colin Campbell under the sponsorship of the Phillips Foundation and the College. "The memory of the late seventies has led people to think we can find something better," he added.

Better than what? Monetary systems fall roughly into two categories: rulebased and discretionary. Under a rulebased system, the economy must be guided in a certain way. For instance, until 1913 this country's economy was on the Gold Standard. The rule stated money supply had to rise and fall with the gold supply.

Under a discretionary system, a central banking authority sets the country's policy and determines money supply. This country has a discretionary system, with the Federal Reserve System as our authority.

A rules system has the advantage of requiring the policymakers to meet a goal, such as constant money growth. But a rule also binds the policymakers' hands in a crisis, such as war, when special measures are needed. A discretionary system does not restrict the policymakers, but that can create trouble as well. Discretionary systems tend to inflate, and the integrity of the policymakers is never guaranteed.

So the basic question facing the conference was, "Can we find a better monetary system than the current discretionary one?" To suggest an answer, six papers were presented by their authors, followed by discussion of each by two or three of the experts present.

The first paper, presented by Robert Barro, professor at the University of Rochester, projected the outcomes of a discretionary system. According to Barro, discretionary policymakers intentionally create surprise inflation and "fool" the private sector, which receives a less valuable dollar for the same output. The output's cost to the country is effectively lowered, or its value increased. However, Barro pointed out, a rational society will come to expect the "surprise" inflation and will cut back on output. The discretionary policy then results in high inflation and low output stagnation such as this country experienced during the recession.

The Federal Reserve got a chance to defend itself. David Lindsey, deputy associate director with the Fed, presented a paper on its policies. He maintained that discretion is the best policy, likening the economy to a car needing a driver to guide it during changing conditions. However, Lindsey's car met with little support not surprising given the conference's purpose. Discussants criticized the paper for being too partial and neglecting to discuss thoroughly weaknesses such as the recession.

Barro's and Lindsey's work set the stage for the other four papers, which focused on variants of a rule-based system. Allan Meltzer, professor at Carnegie Mellon, discussed his data from six monetary systems in our history. It indicated the current system provides more predictability than the Gold Standard, but less than the fixed exchange rates regime in place from 1951 to 1971 -a rule-based system.

Anna Schwartz, who formerly chaired President Reagan's Gold Commission and is now affiliated with the National Bureau of Economic Research, analyzed the Gold Standard's evolution and discussed the conditions under which it might be revived. Participants generally agreed reviving it was impossible, mainly because no standard exists for resetting the price per ounce.

Richard Cooper, a Harvard professor, presented his paper on a fixed exchange rate system. Cooper did not advocate such a system, instead saying the world needs a new "theory of money." He suggested a common currency among the major countries, managed by an international "Super-Fed." Cooper also made perhaps the strongest statement on the current system, saying, "Floating rates cannot endure politically." He anticipates a gradual erosion of the system to eliminate the uncertainty traders now face.

Only one paper actually proposed an alternate system, and, ironically, it was widely criticized. Robert Hall, a Stanford professor, proposed a regime with a contingency rule requiring policymakers to keep deviations in the price level proportional to those in unemployment. Most discussants stated the idea was not feasible.

Hall was not alone in feeling the stings of his colleagues; every paper met opposition of one kind or another. But criticism was always respectful or

delivered with humor. UCLA professor Michael Darby described Hall's style as the "Humphreyesque economics of joy." Ohio State professor Hu McCulloch parried a jab at his lingual abilities by giving his heckler a short English lesson, which drew a huge round of applause.

Throughout the conference the par participants agreed to disagree. Though outstanding individuals with their own notions, they remained committed to the free exchange of ideas the conference represented. Their goal was not to derive any definitive answers, but to generate more thought on what they all feel is an important topic.

The conference has not, in fact, ended here. Final copies of the six papers will be published in one volume for policy circulation and possible classroom use. According to Dougan, there is already a great deal of interest in the volume.

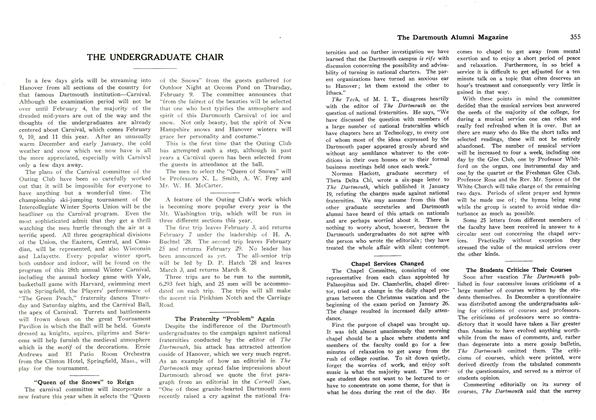

When the construction workers are done, the cluttered hole in the ground between Southand Middle Fayerweather Halls, at left, will be transformed into a pristine kitchenette-coummulti-purpose room like the one at right, in the recently-renovated Cohen-Bissell Lounge. Both projects are part of a campus-wide reemphasis on residential life.

Mark Irish '86 and Dani Klein '84 played a young couple who passed through their twentiesduring the 1970s in the summer Dartmouth Players production of Loose Ends, a playwhich held sociological and political as well as theatrical challenges for guest director PeterPhillips '71.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

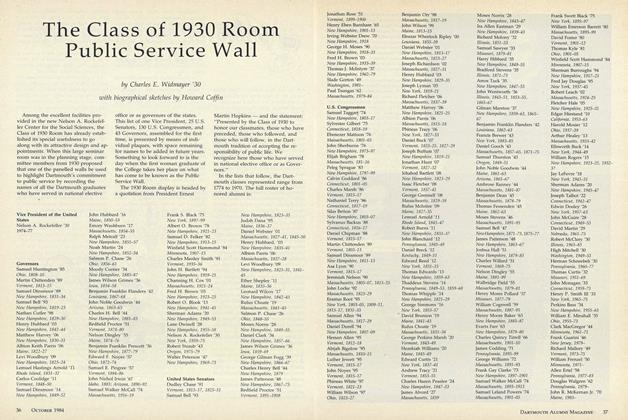

FeatureThe Class of 1930 Room Public Service Wall

October 1984 By Charles E. Widmayer '30 -

Cover Story

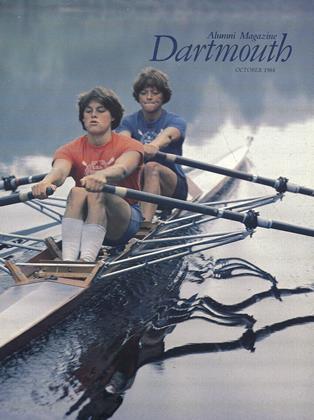

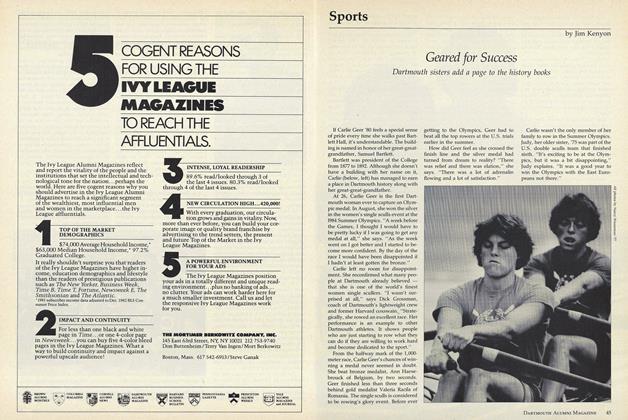

Cover StoryGeared for Success

October 1984 By Jim Kenyon -

Feature

Feature"Little Joe" Wentworth, 1900: Scholar, Athlete, Gentleman

October 1984 By John F. Anderson '34 -

Feature

Feature"The Computer Revolution" Revisited

October 1984 By George O'Connell -

Article

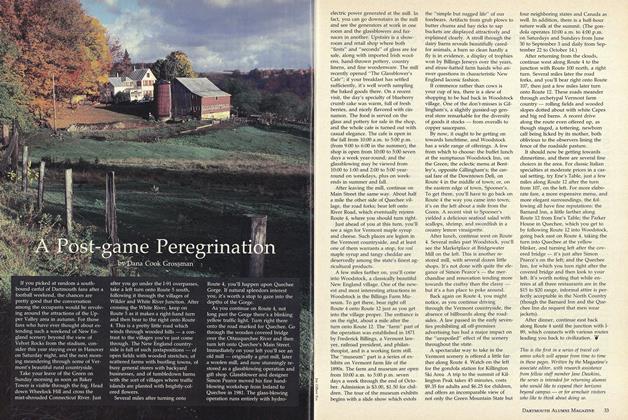

ArticleA Post-game Peregrination

October 1984 By Dana Cook Grossman -

Article

ArticleGetting Better with Age

October 1984 By Gayle Gilman '85