I HAD EXPECTED CUT-AND-DRIED lectures in the "Modern Political Theory" course offered by the government desor partment this past winter. When professor Lucas Swaine, a man of about 30, appeared on the first day wearing a suit and tie, I felt even more certain that the class would be taught in a traditional manner. He announced that he held high expectations for Dartmouth students and that he assigned a high volume of reading each week. No curveballs here, I thought. But then, after Swaine outlined the dates of major papers and exams for his class of nine students, he took a long pause and put down the chalk.

"Things may get a little strange," he warned. He said nothing else.

I exchanged a glance with the student sitting next to me. How could a lecture course on Hobbes, Rousseau and Marx diverge from the norm? The bells from Baker Tower began to chime and Swaine immediately dismissed us from class.

For two weeks normality prevailed. Swaine would talk about the texts and pose questions for us to answer in a brief discussion of the assigned material. One day, after our discussion ended, Swaine disappeared behind the movable blackboard. We assumed he had gone to retrieve handouts explaining our essay paper topic. Instead he came back holding large manila envelopes with bulky contents.

"Do not open these until I leave the room," he announced with a serious tone. "In fact, don't open them until I've exited the building." The class answered with stunned silence. We waited for everyone to receive an envelope and held our collective breath as he grabbed his coat and departed from the classroom. All at once we tore open the packages. The boy sitting one row behind me let out a laugh. The girl seated next to him gasped. Inside each envelope was a gold plastic crown with a paper strip containing our essay topic taped inside the front band. "Is Hobbes's sovereign the master of his subjects or their agent?" was my question.

But I was even more curious about Swaine. I asked about him around campus. I found out he had given each student in his "Contemporary Political Theory" course a party noisemaker with an essay question written inside it.

Then just around midterm Swain again deviated from the standard lecture format by reading a few stanzas of "Pike" by Ted Hughes (who was not as good a poet as his wife, Sylvia Plath, according to Swaine). Then he handed out a plastic toy fish to everyone in class. I could see there was something inside the fish. Its mouth was just large enough to shove a tightly rolled piece of paper into the belly of the fish. But the opening wasn't large enough to pull the paper out. I had to gut the toy to get my second essay question: "To what extent does Karl Marx's critique of civil society and rights improve upon G.W.F. Hegel's treatment of the subject in Elements of the Philosophy of Right?"

When I asked Swaine why he went to great lengths to package these essay questions, he lapsed into the formal profspeak we heard on the first days of class. "Teaching Dartmouth's exceptional students is a real privilege and something to take very seriously," he told me. "I try simply to foster and sustain high levels of scholarship in classes on political theory, partly by making the learning endeavor a bit uncommon."

But what does serious political thought have to do with plastic fish? Swaine would not take the bait. He answered my question somewhat cryptically: "Dartmouth students seem instinctively to understand that being deadly serious about ideas, and having fun with them, are fully compatible."

Users of tanning lamps may A have an increased incidence of skin cancers, and younger users may be at the greatest risk, according to Dartmouth Medical School researchers. Tanning lamps mimic sunlight with their intense, concentrated doses of ultraviolet radiation, a major cause of skin cancer. The team found tanning lamp users were 2.5 times more likely to develop squamous cell carcinoma and 1.5 times more likely to develop basal cell carcinoma than non-users. Economists Eric Edmonds and NinaPavcnik say that imposing economic sanctions to prevent child labor in developing countries exacerbates the problem. In a study of more than 4,700 households in Vietnam, the professors found that as soon as parents can afford it, they cut their childrens' work load and send them to school. As Vietnam integrated its huge rice-farming sector into the global economy, living standards were boosted and a flood of children—about I million—left work for school. The findings suggest that when globalization raises a poor country's incomes, it can cut the rate of child labor dramatically. Sanctions, on the other hand, act to lower household incomes in the targeted countries.

Contributors: Roxanne Khamsi '02 and LauraTemper '02

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

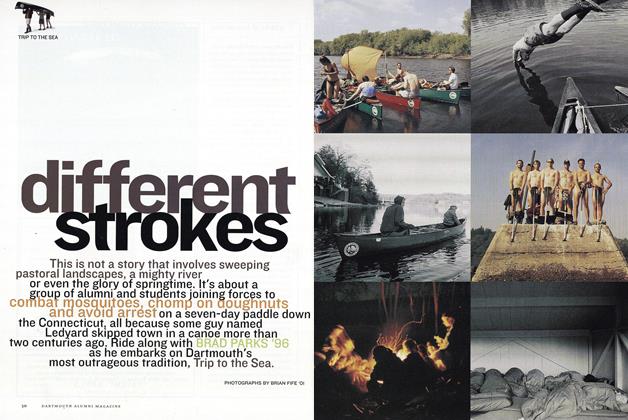

Cover StoryDifferent Strokes

May | June 2002 By Brad Parks ’96 -

Sports

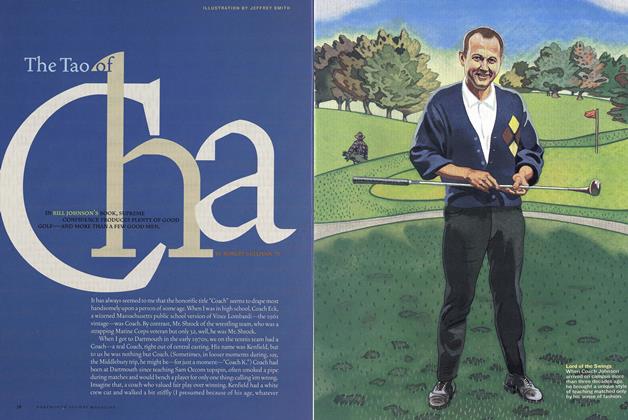

SportsThe Tao of Cha

May | June 2002 By ROBERT SULLIVAN ’75 -

Personal History

Personal HistoryOut of Bounds

May | June 2002 By Sarah Lang Sponheim ’79 -

Article

ArticleSeen & Heard

May | June 2002 -

Article

ArticleFalse Sense of Security

May | June 2002 By Professor Allan C. Stam -

Article

ArticleThe Gift of Education

May | June 2002 By President James Wright