A conversation with Artist-in-Residence Wolf Kahn

In my painting, I deal with things of value to me, things that are restorative, things that deal with tradition, things that have to do with everyday lives. Wolf Kahn, February 1984.

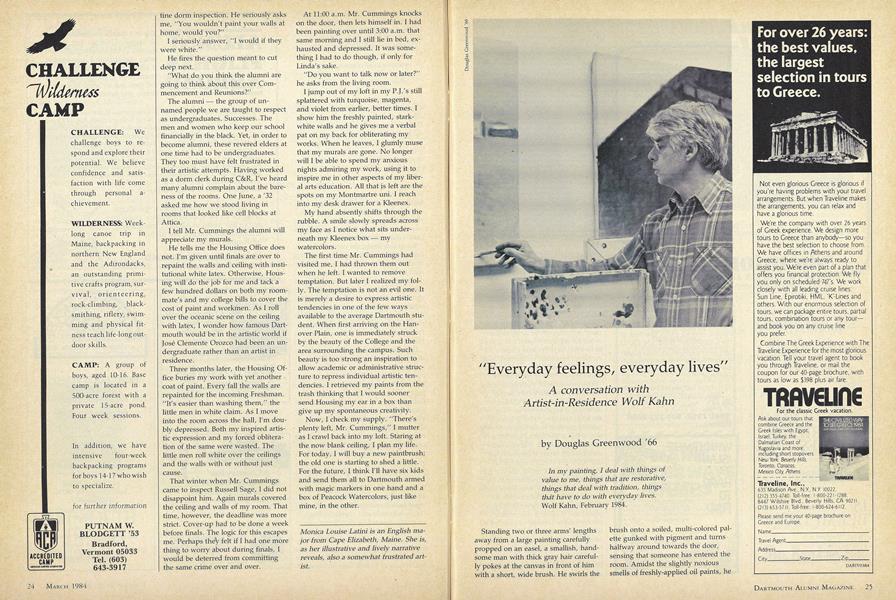

Standing two or three arms' lengths away from a large painting carefully propped on an easel, a smallish, handsome man with thick gray hair carefully pokes at the canvas in front of him with a short, wide brush. He swirls the brush onto a soiled, multi-colored palette gunked with pigment and turns halfway around towards the door, sensing that someone has entered the room. Amidst the slightly noxious smells of freshly-applied oil paints, he seems momentarily lost in the depths of thought. It is 2:30 in the afternoon in one of the nondescript artist studios in the Hop, and the sun and warm air have conspired to convince the unwary that spring is at hand. But it is only mid-February, and veteran Yankees know better. Even Wolf Kahn, a German-born landcape painter who has come to Dartmouth as Artist-in-Residence for the winter term, has learned to love the New England climate. As for New Englanders themselves, Wolf notes, "They are slow in melting, but once they do, they're really terrific."

This conventional wisdom, so aptly expressed, does more than simply mask the more profound thinker underneath; it suggests the very nature of the artist and his art. For it is not so much what Wolf Kahn sees as how he sees it that is the hallmark of his style. When his early work is juxtaposed with his later work, it becomes clear that Kahn has clarified and harmonized his vision of reality. He is a masterful colorist, a man sensitive to the feel and pluck of the land. Kahn chose landscape as his subject matter, he said, because it can never be fully explored and because it is accessible to all, not simply to those who can afford to hang his canvases in their living rooms. "If a truck driver sees my work a row of trees for example he reorganizes his view of reality." I ask how many truck drivers see his work and he continues, "You know, that is one of the things that bothers me. Art shouldn't exist just for aesthetes. But an artist doesn't have the luxury of dealing with all levels of society. In its own way, of course, art cuts across all this, because it has to do with everyday feelings enjoying a nice day, being moody, being out in the country it's something we all share."

Kahn talks volubly as he paints. "An artist," he says, "has to learn to become an interesting person. Some learn about life from reading, some from the people they know, and some, by other means altogether. The only way to so# out your feelings is by living a little and by painting a lot." He continues, almost non-stop, "An artist uses his art for self-definition; to find •where he stands. It's not a matter of simply making a product, but a matter of defining a response to life, of fixing it."

Commercially successful for the last 20 years or so, Kahn is considered by many to be one of the foremost landscape artists painting in America today. Although he was elected to the prestigious American Institute of Arts and Letters during his tenure at Dartmouth, Kahn tosses off the honor in mock-arrogance. "I am much more self-important now. The next time we meet, you and I," and here he turns away from his canvas to look me headon, "I'll be a pompous old man wearing a top hat." It is hard to imagine a scene less likely, for if there is anything that Kahn projects, it is his genuineness, his likeableness, his earthiness. After all, you don't ordinarily see pompous old men wearing beat-up Levi's with green tee-shirts tucked underneath bright red plaids.

As a man who fled Nazi Germany and spent a Bohemian apprenticeship in the likes of New York City, Chicago, and San Francisco, Wolf Kahn knows the meaning of hard times. Has money changed his life? "I hope not. Once you make it, you need to be careful about taking it too seriously. I really don't like [artistic] success being equated with financial success," Kahn sighs, the implication being that in America, at least, the correlation is more than just a passing assumption. "No," Kahn shakes his head, looking at his watch (he's catching the 3:00 flight from Lebanon down to LaGuardia), "I didn't go into art to work for the rich." True enough, but chances are, the evocative landscapes of Wolf Kahn won't be known to as many truck drivers as he would like.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureBraving the Alps

March 1984 By Jack Aley '66 -

Feature

FeatureShaping Public Policy: The Washington Internship Program

March 1984 By Frank Smallwood '51 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA New in the Neighborhood

March 1984 By Debbie Schupack '84 -

Feature

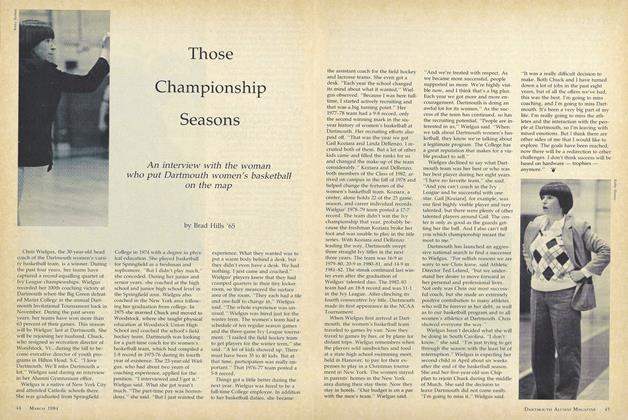

FeatureThose Championship Seasons

March 1984 By Brad Hills '65 -

Article

ArticleThe Price of Art

March 1984 By Monica Louise Latini '84 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1963

March 1984 By Harry R. Zlokower