I set out to analyze the nature of the relationship and the rapport between students and professors at Dartmouth perhaps define some complicated infrastructure, uncode some secret, or discover some deep-rooted problem and propose a brilliant solution. But what I found was that some professors are easier to talk to than others; some students pursue relationships more than others; and some relationships are better than others. All in all, the professors here are very accessible, and, yes, human. In the end, Sue Brandenburg '84 summed it up for me when she said, "Talking to professors is just like talking to people."

This term I am working independently with two professors and closely with a third. I knock on a professor's door almost every day and am in a professor's office at least once or twice a week. While other students tell me this is extreme, the general student consensus is that professors do make themselves available to the students, and most professors are accessible outside the classroom. While meeting me at three o'clock Sunday, daughter in tow for lack of babysitter, English professor Cleopatra Mathis said, "The first criterion of any good teacher is availability. It forms a bond with the student by showing him or her that you care. It then gives the student added desire to succeed because now, in addition to pleasing himself, his parents etc., he also wants to please the professor." She added, "It's difficult for me to say 'l'm busy,' because I know how hard it is to be a student and be in the position of always asking and taking. If that asking is met with indifference or hostility, the student is going to be more insecure and ask less. I try to keep myself cheerfully available."

This bond is a valuable channel for the flow of wisdom. Mathis continued, "The close student-professor relationship at Dartmouth is critical to the nature and purpose of the school: to provide private education." Professor of Biology emeritus Walter Stockmayer expanded on this point. When I asked whether he thought the emphasis was on undergraduates, graduate students, or research, he replied, "It's on enjoying the acquisition of knowledge at any level."

"Do you ever learn from students?" I asked Stockmayer. "Yes. Oh, yes," he replied, explaining that from freshmen's questions he may learn that there is a better way to explain something, while from a higher-level student the process may well be more complicated. "In fact, one student taught me more than I taught him. It was a partnership from the word go." Students are generally not aware of this give-and-take, since they are constantly in the position of being judged. They are so used to taking that it becomes difficult to realize that they can give, too.

Most students and many professors, too feel comfortable with an informal relationship only outside the formal classroom situation, that is, after the semester has ended. I was surprised to learn this, since I feel more comfortable inviting a professor to dinner or to a cocktail party while I am still taking a course. My feeling is based, I think, on having something in common, the most obvious being material from the course. I know of one student, however, who shares a love of running with a professor; so they run together. Another student told me that she feels a common bond with her professor because they are both Greek. It is just like talking to people.

Every student from freshman to senior to whom I posed the question: "If you need to talk to a professor, can you?" answered, "Yes." The bottom line seems to be a philosophy like that of mathematics professor William Slesnick, who says, "We're here with our doors open. Students who want to come in will. Those who don't want to or don't have the gumption to come in, don't." Another professor says, "People tend to get what they need. If they need to talk to a professor, they will. If they don't, they won't." Professor of Religion Fred Berthold, however, wants to go beyond such a "functionalist" approach: "Need is a difficult word. In religion class, we are talking about earth-shattering topics like human suffering. The fact that six million people were killed in the Holocaust is difficult for anyone to discuss, and I think there is a real need for students to discuss this." He mentioned in his class that he is disturbed by the fact that students don't come in to see him during office hours and wonders why. "If they're interested in a topic, they should be able to discuss it with me."

I find the professors very accessible. Though they are busy, most professors make it a point to let students know that when they have time, they will be available. I met with my thesis advisor last February and the first words out of his mouth were "I have a meeting in a half hour." But then, after all our business was conducted and I was getting ready to leave, he said, "How's the rest of your term going?" That gave me the opportunity to open up a more personal channel or to say, "Fine, thanks. See you in a couple of weeks." Again, just like talking to a person. A friend of mine said of one of her professors, "I thought he was the greatest guy, because I went in to talk about a paper and he asked me what I was doing next year. It was a little thing, but it let me know that he cared." Of course, some professors skip the little things; relationships vary from professor to professor. A freshman I spoke to complained that her seminar professor was extremely condescending, so of course she was not going to be dropping by for any chit-chat or expert advice. Similarly, a senior complains of one of her professors, "We're in a seminar. It's only six people but we sit in scattered seats. God forbid we should form a circle or a discussion. And he calls people by the wrong names!"

Both professors and students agree that there could profitably be more outside-the-classroom contact. With the new cluster proposal, faculty masters will be assigned to clusters for just that reason. One professor is skeptical: "It is like a small midwestern mining town in 1900. Some children were starving and illiterate, but most were fine. Then someone decided that these people needed help parenting. Suddenly there were programs on nutrition, education, child care. When all was said and done, some children were starving and illiterate, and most were fine." Most, however, are not so skeptical. The cluster masters will provide an opportunity for students to get to know faculty members more closely, more fully, and in a more informal setting.

Is it better or worse at other schools? A Dartmouth professor who is a visiting professor at the University of Virginia this term says he gets a lot of work done down there. No students knock on his door. A friend who recently took a job at Harvard's history department says she was hired specifically to keep the professors inaccessible - to defer calls, and to refuse to give out home phone numbers. (Here, professors' home numbers are published in the student directory, and we are often encouraged to call professors at home.) As classics professor Edward Bradley, talking of the spirit of fellowship between students and professors at Dartmouth, said, "It may be good or it may be bad elsewhere but I know it's good here."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

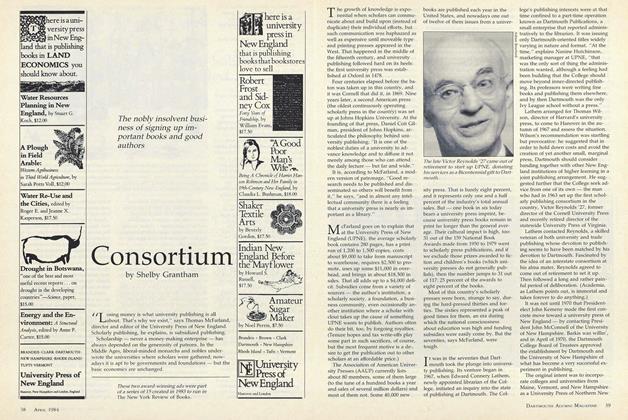

Cover StoryConsortium

April 1984 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureHanover Sabbatical

April 1984 By Robert Conn '61 -

Feature

FeatureCenters of Excellence and the Survival of Creativity

April 1984 By O. Ross Mclntyre '53 -

Feature

FeatureRobert Frost Keeps Me Company Often Uninvited

April 1984 By Kenneth Andler '26 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

April 1984 By William G. Long -

Class Notes

Class Notes1963

April 1984 By Harry R. Zlokower

Debbie Schupack '84

-

Article

ArticleFreshman Book to Aegis

November 1983 By Debbie Schupack '84 -

Article

ArticleWhy "Why Not?"

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1984 By Debbie Schupack '84 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA New in the Neighborhood

MARCH 1984 By Debbie Schupack '84 -

Feature

FeatureThe Granite of New Hampshire

MAY 1984 By Debbie Schupack '84 -

Article

ArticleGetting Ahead on the Mommytrack

OCTOBER 1990 By Debbie Schupack '84