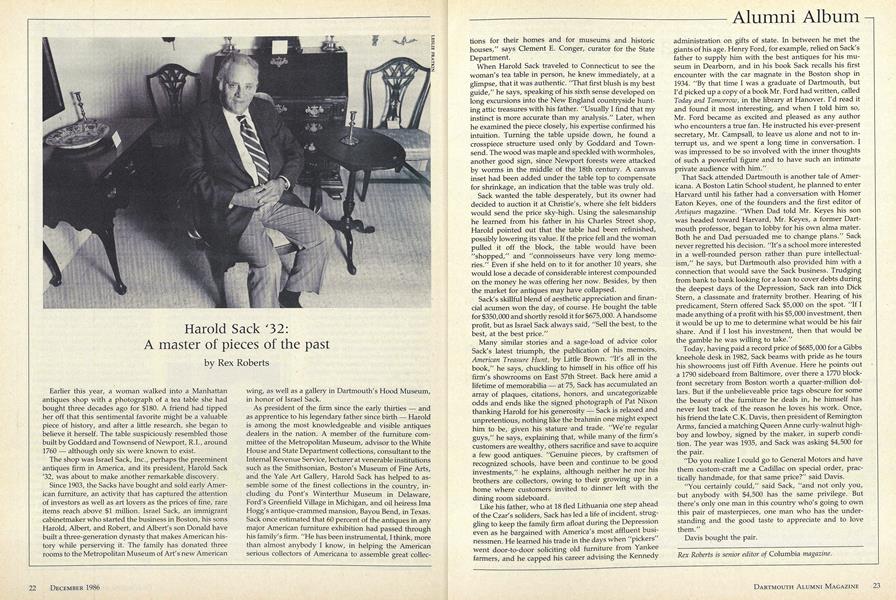

Earlier this year, a woman walked into a Manhattan antiques shop with a photograph of a tea table she had bought three decades ago for $l80. A friend had tipped her off that this sentimental favorite might be a valuable piece of history, and after a little research, she began to believe it herself. The table suspiciously resembled those built by Goddard and Townsend of Newport, R.I., around 1760 although only six were known to exist.

The shop was Israel Sack, Inc., perhaps the preeminent antiques firm in America, and its president, Harold Sack '32, was about to make another remarkable discovery.

Since 1903, the Sacks have bought and sold early American furniture, an activity that has captured the attention of investors as well as art lovers as the prices of fine,'rare items reach above $1 million. Israel Sack, an immigrant cabinetmaker who started the business in Boston, his sons Harold, Albert, and Robert, and Albert's son Donald have built a three-generation dynasty that makes American history while perserving it. The family has donated three rooms to the Metropolitan Museum of Art's new American wing, as well as a gallery in Dartmouth's Hood Museum, in honor of Israel Sack.

As president of the firm since the early thirties and as apprentice to his legendary father since birth Harold is among the most knowledgeable and visible antiques dealers in the nation. A member of the furniture committee of the Metropolitan Museum, advisor to the White House and State Department collections, consultant to the Internal Revenue Service, lecturer at venerable institutions such as the Smithsonian, Boston's Museum of Fine Arts, and the Yale Art Gallery, Harold Sack has helped to assemble some of the finest collections in the country, including du Pont's Winterthur Museum in Delaware, Ford's Greenfield Village in Michigan, and oil heiress Ima Hogg's antique-crammed mansion, Bayou Bend, in Texas. Sack once estimated that 60 percent of the antiques in any major American furniture exhibition had passed through his family's firm. "He has been instrumental, I think, more than almost anybody I know, in helping the American serious collectors of Americana to assemble great collections for their homes and for museums and historic houses," says Clement E. Conger, curator for the State Department.

When Harold Sack traveled to Connecticut to see the woman's tea table in person, he knew immediately, at a glimpse, that it was authentic. "That first blush is my best guide," he says, speaking of his sixth sense developed on long excursions into the New England countryside hunting attic treasures with his father. "Usually I find that my instinct is more accurate than my analysis." Later, when he examined the piece closely, his expertise confirmed his intuition. Turning the table upside down, he found a crosspiece structure used only by Goddard and Town send. The wood was maple and speckled with wormholes, another good sign, since Newport forests were attacked by worms in the middle of the 18th century. A canvas inset had been added under the table top to compensate for shrinkage, an indication that the table was truly old.

Sack wanted the table desperately, but its owner had decided to auction it at Christie's, where she felt bidders would send the price sky-high. Using the salesmanship he learned from his father in his Charles Street shop, Harold pointed out that the table had been refinished, possibly lowering its value. If the price fell and the woman pulled it off the block, the table would have been "shopped," and "connoisseurs have very long memories." Even if she held on to it for another 10 years, she would lose a decade of considerable interest compounded on the money he was offering her now. Besides, by then the market for antiques may have collapsed.

Sack's skillful blend of aesthetic appreciation and financial acumen won the day, of course. He bought the table for $350,000 and shortly resold it for $675,000. A handsome profit, but as Israel Sack always said, "Sell the best, to the best, at the best price."

Many similar stories and a sage-load of advice color Sack's latest triumph, the publication of his memoirs, American Treasure Hunt, by Little Brown. "It's all in the book," he says, chuckling to himself in his office off his firm's showrooms on East 57th Street. Back here amid a lifetime of memorabilia at 75, Sack has accumulated an array of plaques, citations, honors, and uncategorizable odds and ends like the signed photograph of Pat Nixon thanking Harold for his generosity Sack is relaxed and unpretentious, nothing like the brahmin one might expect him to be, given his stature and trade. "We re regular guys," he says, explaining that, while many of the firm s customers are wealthy, others sacrifice and save to acquire a few good antiques. "Genuine pieces, by craftsmen of recognized schools, have been and continue to be good investments," he explains, although neither he nor his brothers are collectors, owing to their growing up in a home where customers invited to dinner left with the dining room sideboard.

Like his father, who at 18 fled Lithuania one step ahead of the Czar's soliders, Sack has led a life of incident, struggling to keep the family firm afloat during the Depression even as he bargained with America's most affluent businessmen. He learned his trade in the days when "pickers" went door-to-door soliciting old furniture from Yankee farmers, and he capped his career advising the Kennedy administration on gifts of state. In between he met the giants of his age. Henry Ford, for example, relied on Sack's father to supply him with the best antiques for his museum in Dearborn, and in his book Sack recalls his first encounter with the car magnate in the Boston shop in 1934. "By that time I was a graduate of Dartmouth, but I'd picked up a copy of a book Mr. Ford had written, called Today and Tomorrow, in the library at Hanover. I'd read it and found it most interesting, and when I told him so, Mr. Ford became as excited and pleased as any author who encounters a true fan. He instructed his ever-present secretary, Mr. Campsall, to leave us alone and not to interrupt us, and we spent a long time in conversation. I was impressed to be so involved with the inner thoughts of such a powerful figure and to have such an intimate private audience with him."

That Sack attended Dartmouth is another tale of Americana. A Boston Latin School student, he planned to enter Harvard until his father had a conversation with Homer Eaton Keyes, one of the founders and the first editor of Antiques magazine. "When Dad told Mr. Keyes his son was headed toward Harvard, Mr. Keyes, a former Dartmouth professor, began to lobby for his own alma mater. Both he and Dad persuaded me to change plans." Sack never regretted his decision. "It's a school more interested in a well-rounded person rather than pure intellectualism," he says, but Dartmouth also provided him with a connection that would save the Sack business. Trudging from bank to bank looking for a loan to cover debts during the deepest days of the Depression, Sack ran into Dick Stern, a classmate and fraternity brother. Hearing of his predicament, Stern offered Sack $5,000 on the spot. "If I made anything of a profit with his $5,000 investment, then it would be up to me to determine what would be his fair share. And if I lost his investment, then that would be the gamble he was willing to take."

Today, having paid a record price of $685,000 for a Gibbs kneehole desk in 1982, Sack beams with pride as he tours his showrooms just off Fifth Avenue. Here he points out a 1790 sideboard from Baltimore, over there a 1770 blockfront secretary from Boston worth a quarter-million dollars. But if the unbelieveable price tags obscure for some the beauty of the furniture he deals in, he himself has never lost track of the reason he loves his work. Once, his friend the late C.K. Davis, then president of Remington Arms, fancied a matching Queen Anne curly-walnut highboy and lowboy, signed by the maker, in superb condition. The year was 1935, and Sack was asking $4,500 for the pair.

"Do you realize I could go to General Motors and have them custom-craft me a Cadillac on special order, practically handmade, for that same price?" said Davis.

"You certainly could," said Sack, "and not only you, but anybody with $4,500 has the same privilege. But there's only one man in this country who's going to own this pair of masterpieces, one man who has the understanding and the good taste to appreciate and to love them."

Davis bought the pair.

Rex Roberts is senior editor of Columbia magazine

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

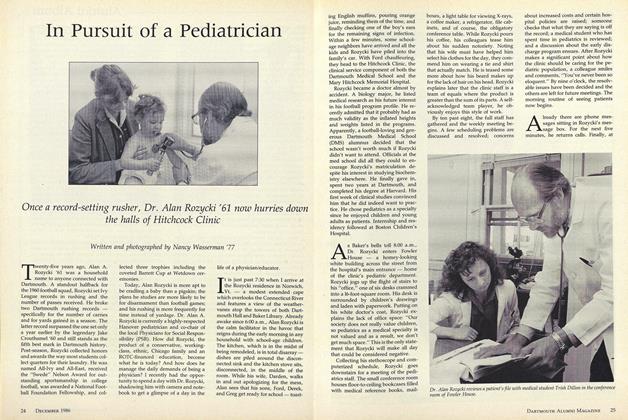

FeatureIn Pursuit of a Pediatrician

December 1986 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Feature

FeatureLawyers, Liberal Arts, and the Cold War

December 1986 By Weyman I. Lundquist '52 -

Feature

FeatureRichard Hovey: The Incomplete Arthurian

December 1986 By Daniel P. Nastali -

Feature

FeatureSnowmaking at the Dartmouth Skiway: Taking the Wonder Out of Winter

December 1986 By Lee Michaelides -

Article

ArticleMarianne Alverson: At home in many worlds

December 1986 By Lee McDavid -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

December 1986 By C. E. Widmayer

Rex Roberts

Article

-

Article

ArticleProf. Feldman Dies

November 1947 -

Article

ArticleGifts

September 1979 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Renews Its Bonds with England

JULY 1973 By JOAN HIER -

Article

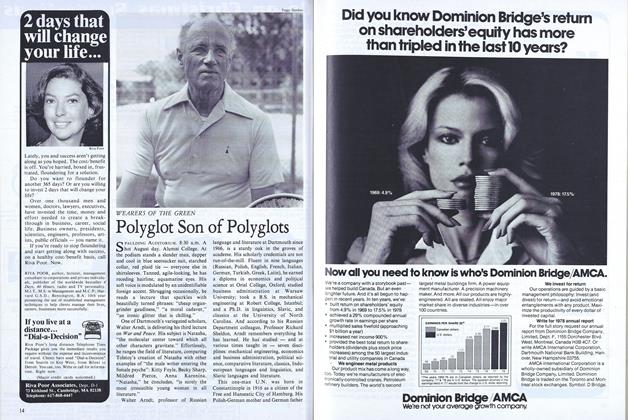

ArticlePolyglot Son of Polyglots

October 1979 By NARDI REEDER CAMPION -

Article

ArticleThe Canoe Club

June 1947 By Pete Owen '47 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

May 1961 By TOM DALGLISH '61