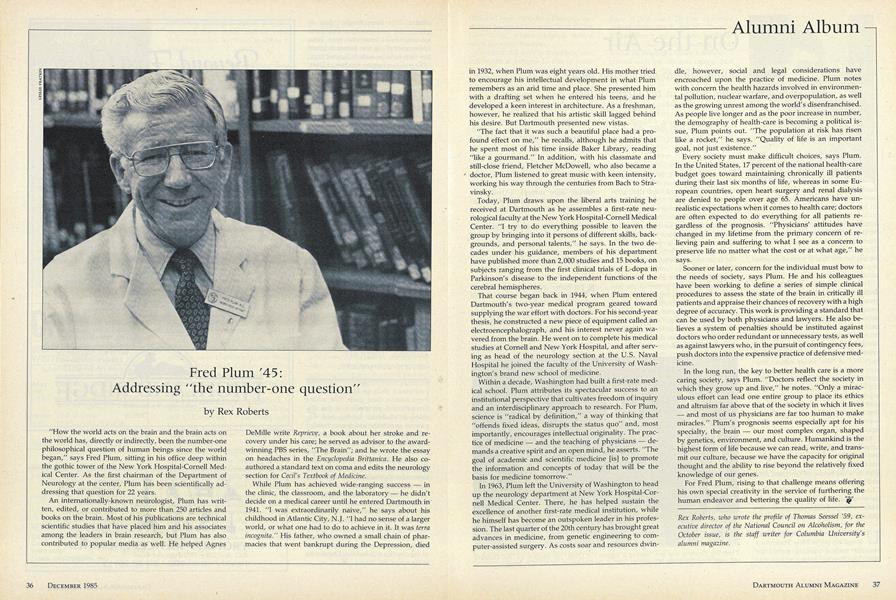

"How the world acts on the brain and the brain acts on the world has, directly or indirectly, been the number-one philosophical question of human beings since the world began," says Fred Plum, sitting in his office deep within the gothic tower of the New York Hospital-Cornell Medical Center. As the first chairman of the Department of Neurology at the center, Plum has been scientifically addressing that question for 22 years.

An internationally-known neurologist, Plum has written, edited, or contributed to more than 250 articles and books on the brain. Most of his publications are technical scientific studies that have placed him and his associates among the leaders in brain research, but Plum has also contributed to popular media as well. He helped Agnes DeMille write Reprieve, a book about her stroke and recovery under his care; he served as advisor to the awardwinning PBS series, "The Brain"; and he wrote the essay on headaches in the Encyclopedia Brittanica. He also coauthored a standard text on coma and edits the neurology section for Cecil's Textbook of Medicine.

While Plum has achieved wide-ranging success in the clinic, the classroom, and the laboratory he didn't decide on a medical career until he entered Dartmouth in 1941. "I was extraordinarily naive," he says about his childhood in Atlantic City, N.J, "I had no sense of a larger world, or what one had to do to achieve in it. It was terraincognita." His father, who owned a small chain of pharmacies that went bankrupt during the Depression, died in 1932, when Plum was eight years old. His mother tried to encourage his intellectual development in what Plum remembers as an arid time and place. She presented him with a drafting set when he entered his teens, and he developed a keen interest in architecture. As a freshman, however, he realized that his artistic skill lagged behind his desire. But Dartmouth presented new vistas.

"The fact that it was such a beautiful place had a profound effect on me," he recalls, although he admits that he spent most of his time inside Baker Library, reading "like a gourmand." In addition, with his classmate and still-close friend, Fletcher McDowell, who also became a doctor, Plum listened to great music with keen intensity, working his way through the centuries from Bach to Stravinsky.

Today, Plum draws upon the liberal arts training he received at Dartmouth as he assembles a first-rate neurological faculty at the New York Hospital-Cornell Medical Center. "I try to do everything possible to leaven the group by bringing into it persons of different skills, backgrounds, and personal talents," he says. In the two decades under his guidance, members of his department have published more than 2,000 studies and 15 books, on subjects ranging from the first clinical trials of L-dopa in Parkinson's disease to the independent functions of the cerebral hemispheres.

That course began back in 1944, when Plum entered Dartmouth's two-year medical program geared toward supplying the war effort with doctors. For his second-year thesis, he constructed a new piece of equipment called an electroencephalograph, and his interest never again wavered from the brain. He went on to complete his medical studies at Cornell and New York Hospital, and after serving as head of the neurology section at the U.S. Naval Hospital he joined the faculty of the University of Washington's brand new school of medicine.

Within a decade, Washington had built a first-rate medical school. Plum attributes its spectacular success to an institutional perspective that cultivates freedom of inquiry and an interdisciplinary approach to research. For Plum, science is "radical by definition," a way of thinking that "offends fixed ideas, disrupts the status quo" and, most importantly, encourages intellectual originality. The practice of medicine - and the teaching of physicians - demands a creative spirit and an open mind, he asserts. "The goal of academic and scientific medicine [is] to promote the information and concepts of today that will be the basis for medicine tomorrow."

In 1963, Plum left the University of Washington to head up the neurology department at New York Hospital-Cornell Medical Center. There, he has helped sustain the excellence of another first-rate medical institution, while he himself has become an outspoken leader in his profession. The last quarter of the 20th century has brought great advances in medicine, from genetic engineering to computer-assisted surgery. As costs soar and resources dwindle, however, social and legal considerations have encroached upon the practice of medicine. Plum notes with concern the health hazards involved in environmental pollution, nuclear warfare, and overpopulation, as well as the growing unrest among the world's disenfranchised. As people live longer and as the poor increase in number, the demography of health-care is becoming a political issue, Plum points out. "The population at risk has risen like a rocket," he says. "Quality of life is an important goal, not just existence."

Every society must make difficult choices, says Plum. In the United States, 17 percent of the national health-care budget goes toward maintaining chronically ill patients during their last six months of life, whereas in some European countries, open heart surgery and renal dialysis are denied to people over age 65. Americans have unrealistic expectations when it comes to health care; doctors are often expected to do everything for all patients regardless of the prognosis. "Physicians' attitudes have changed in my lifetime from the primary concern of relieving pain and suffering to what I see as a concern to preserve life no matter what the cost or at what age," he says.

Sooner or later, concern for the individual must bow to the needs of society, says Plum. He and his colleagues have been working to define a series of simple clinical procedures to assess the state of the brain in critically ill patients and appraise their chances of recovery with a high degree of accuracy. This work is providing a standard that can be used by both physicians and lawyers. He also believes a system of penalties should be instituted against doctors who order redundant or unnecessary tests, as well as against lawyers who, in the pursuit of contingency fees, push doctors into the expensive practice of defensive medicine.

In the long run, the key to better health care is a more caring society, says Plum. "Doctors reflect the society in which they grow up and live," he notes. "Only a miraculous effort can lead one entire group to place its ethics and altruism far above that of the society in which it lives - and most of us physicians are far too human to make miracles." Plum's prognosis seems especially apt for his specialty, the brain our most complex organ, shaped by genetics, environment, and culture. Humankind is the highest form of life because we can read, write, and transit our culture, because we have the capacity for original thought and the ability to rise beyond the relatively fixed knowledge of our genes.

For Fred Plum, rising to that challenge means offering his own special creativity in the service of furthering the human endeavor and bettering the quality of life.

Rex Roberts, who wrote the profile of Thomas Seessel '59, executive director of the National Council on Alcoholism, for theOctober issue, is the staff writer for Columbia University'salumni magazine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureOn the Air

December 1985 By Michael Berg '82 -

Feature

FeatureThe Impact of Section 504

December 1985 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Cover Story

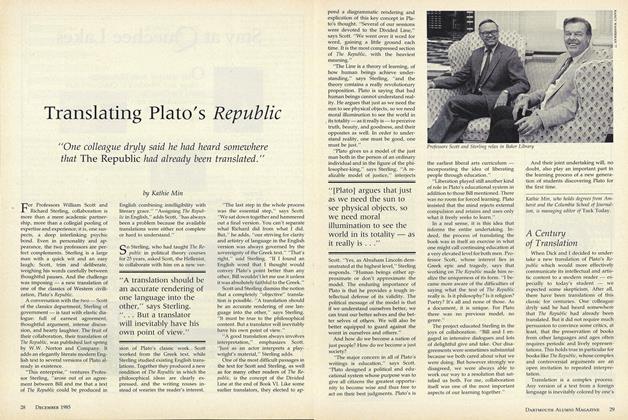

Cover StoryTranslating Plato's Republic

December 1985 By Kathie Min -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Century of Translation

December 1985 By WILLIAM C. SCOTT -

Cover Story

Cover StoryFragments of papyrus

December 1985 By RICHARD W. STERLING -

Article

ArticleAstronomer Gary Wegner: Seeker of another world

December 1985 By Dave Coburn