"One colleague dryly said he had heard somewherethat The Republic had already been translated."

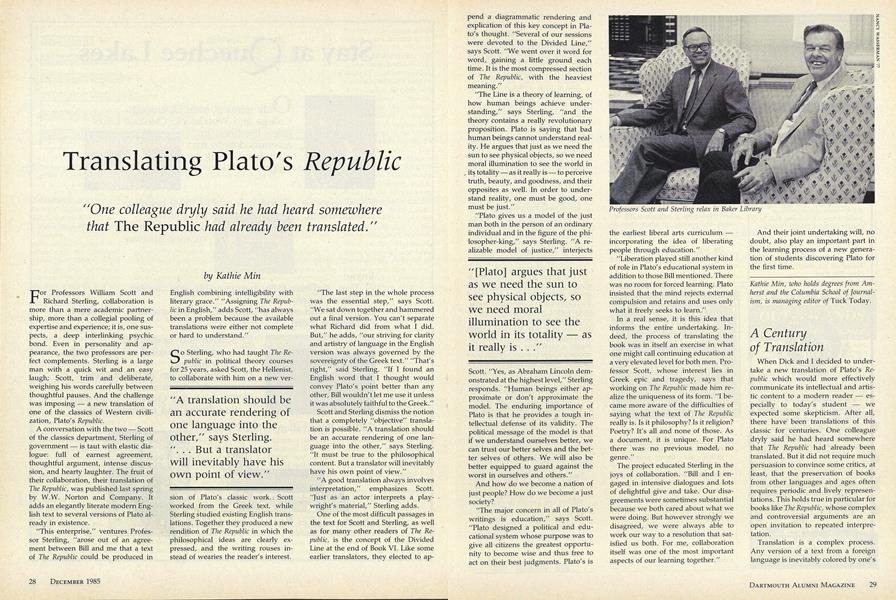

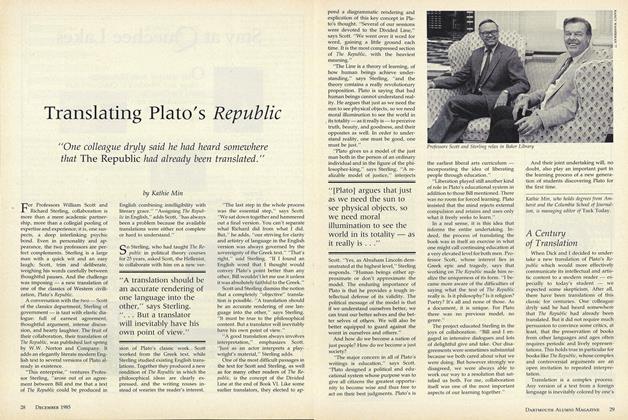

For Professors William Scott and Richard Sterling, collaboration is more than a mere academic partnership, more than a collegial pooling of expertise and experience; it is, one suspects, a deep interlinking psychic bond. Even in personality and appearance, the two professors are perfect complements. Sterling is a large man with a quick wit and an easy laugh; Scott, trim and deliberate, weighing his words carefully between thoughtful pauses. And the challenge was imposing - a new translation of one of the classics of Western civilization, Plato's Republic.

A conversation with the two Scott of the classics department, Sterling of government - is taut with elastic dialogue: full of earnest agreement, thoughtful argument, intense discussion, and hearty laughter. The fruit of their collaboration, their translation of The Republic, was published last spring by W.W. Norton and Company. It adds an elegantly literate modern English text to several versions of Plato already in existence.

"This enterprise," ventures Professor Sterling, "arose out of an agreement between Bill and me that a text of The Republic could be produced in English combining intelligibility with literary grace." "Assigning The Republic in English," adds Scott, "has always been a problem because the available translations were either not complete or hard to understand."

So Sterling, who had taught The Republic in political theory courses for 25 years, asked Scott, the Hellenist, to collaborate with him on a new version of Plato's classic work. Scott worked from the Greek text, while Sterling studied existing English translations. Together they produced a new rendition of The Republic in which the philosophical ideas are clearly expressed, and the writing rouses instead of wearies the reader's interest.

"The last step in the whole process was the essential step," says Scott. "We sat down together and hammered out a final version. You can't separate what Richard did from what I did. But," he adds, "our striving for clarity and artistry of language in the English version was always governed by the sovereignty of the Greek text." "That's right," said Sterling. "If I found an English word that I thought would convey Plato's point better than any other, Bill wouldn't let me use it unless it was absolutely faithful to the Greek."

Scott and Sterling dismiss the notion that a completely "objective" translation is possible. "A translation should be an accurate rendering of one language into the other," says Sterling. "It must be true to the philosophical content. But a translator will inevitably have his own point of view."

"A good translation always involves interpretation," emphasizes Scott. "Just as an actor interprets a playwright's material," Sterling adds. One of the most difficult passages in the text for Scott and Sterling, as well as for many other readers of The Republic, is the concept of the Divided Line at the end of Book VI. Like some earlier translators, they elected to append a diagrammatic rendering and explication of this key concept in Plato's thought. "Several of our sessions were devoted to the Divided Line," says Scott. "We went over it word for word, gaining a little ground each time. It is the most compressed section of The Republic, with the heaviest meaning."

"The Line is a theory of learning, of how human beings achieve understanding," says Sterling, "and the theory contains a really revolutionary proposition. Plato is saying that bad human beings cannot understand reality. He argues that just as we need the sun to see physical objects, so we need moral illumination to see the world in its totality - as it really is - to perceive truth, beauty, and goodness, and their opposites as well. In order to understand reality, one must be good, one must be just." "Plato gives us a model of the just man both in the person of an ordinary individual and in the figure of the philosopher-king," says Sterling. "A re- alizable model of justice," interjects Scott. "Yes, as Abraham Lincoln demonstrated at the highest level," Sterling responds. "Human beings either approximate or don't approximate the model. The enduring importance of Plato is that he provides a tough intellectual defense of its validity. The political message of the model is that if we understand ourselves better, we can trust our better selves and the better selves of others. We will also be better equipped to guard against the worst in ourselves and others."

And how do we become a nation of just people? How do we become a just society?

"The major concern in all of Plato's writings is education," says Scott. "Plato designed a political and eduational system whose purpose was to give all citizens the greatest opportunity to become wise and thus free to act on their best judgments. Plato's is the earliest liberal arts curriculum incorporating the idea of liberating people through education." "Liberation played still another kind of role in Plato's educational system in addition to those Bill mentioned. There was no room for forced learning. Plato insisted that the mind rejects external compulsion and retains and uses only what it freely seeks to learn."

In a real sense, it is this idea that informs the entire undertaking. Indeed, the process of translating the book was in itself an exercise in what one might call continuing education at a very elevated level for both men. Professor Scott, whose interest lies in Greek epic and tragedy, says that working on The Republic made him realize the uniqueness of its form. "I became more aware of the difficulties of saying what the text of The Republic really is. Is it philosophy? Is it religion? Poetry? It's all and none of those. As a document, it is unique. For Plato there was no previous model; no genre."

The project educated Sterling in the joys of collaboration. "Bill and I engaged in intensive dialogues and lots of delightful give and take. Our disagreements were sometimes substantial because we both cared about what we were doing. But however strongly we disagreed, we were always able to work our way to a resolution that satisfied us both. For me, collaboration itself was one of the most important aspects of our learning together."

And their joint undertaking will, no doubt, also play an important part in the learning process of a new generation of students discovering Plato for the first time.

Professors Scott and Sterling relax in Baker Library

"A translation should be an accurate rendering of one language into the other," says Sterling. "... But a translator will inevitably have his own point of view."

"[Plato] argues that just as we need the sun to see physical objects, so we need moral illumination to see the world in its totality - as it really is ..."

Kathie Min, who holds degrees from Amherst and the Columbia School of Journalism, is managing editor of Tuck Today.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureOn the Air

December 1985 By Michael Berg '82 -

Feature

FeatureThe Impact of Section 504

December 1985 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Century of Translation

December 1985 By WILLIAM C. SCOTT -

Cover Story

Cover StoryFragments of papyrus

December 1985 By RICHARD W. STERLING -

Article

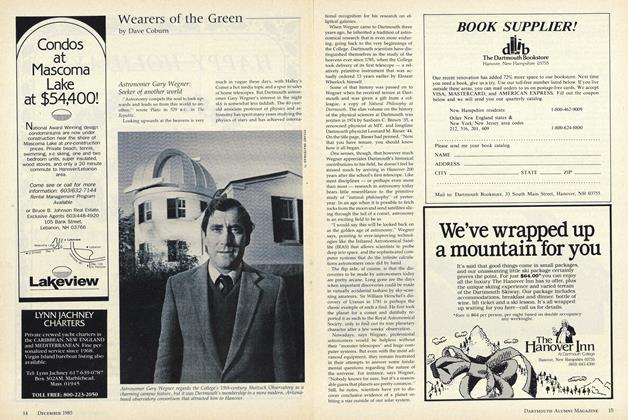

ArticleAstronomer Gary Wegner: Seeker of another world

December 1985 By Dave Coburn -

Sports

SportsThe Man Behind the Berry Sports Center

December 1985 By Jim Kenyon

Features

-

Feature

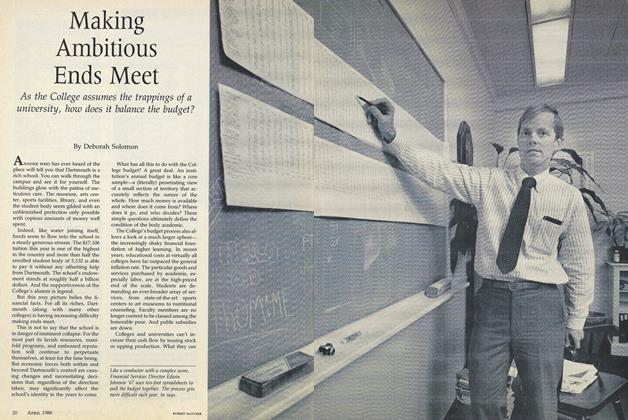

FeatureMaking Ambitious Ends Meet

APRIL 1988 By Deborah Solomon -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

July/August 2007 By Marrin Robinson '82, Marrin Robinson '82 -

Feature

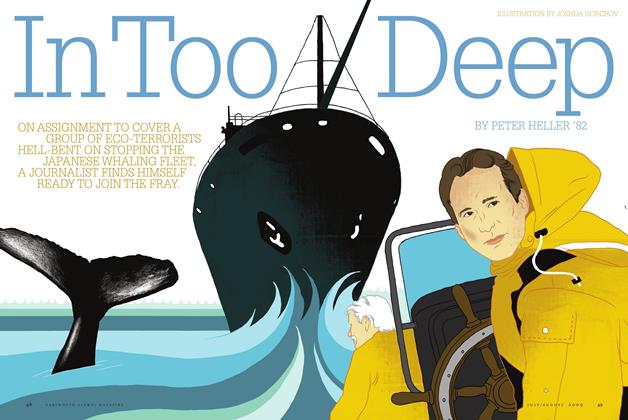

FeatureIn Too Deep

July/Aug 2009 By PETER HELLER ’82 -

Feature

FeatureOne Question for Mr. Frost

MARCH • 1987 By Philip Booth '47 -

Feature

FeatureFirst Panel Discussion

October 1951 By SIR GEOFFREY CROWTHER -

FEATURE

FEATUREThe Beat of Terror

JULY | AUGUST 2015 By STUART A. REID ’08