What the College has done (and hasn't)to make the campus accessible for the handicapped

For most Dartmouth students, life at the College begins with their Freshman Trip - a four-day excursion hiking, biking, or canoeing around the North Country - and ends four years later with a jaunt up and down eight steps to collect their diplomas. Along the way they will negotiate countless flights of stairs to their dorm rooms, to classes, the stacks, and offices all over campus. They will also attend concerts, plays, football games, play softball or maybe tennis, and undoubtedly study away from Hanover in one of Dartmouth's foreign study programs. But for a student confined to a wheelchair or even on crutches, this maneuvering can be as great a challenge as Dartmouth's rigorous academic load.

Many familiar with the College's rural campus, the multitude of steps in and out of Dartmouth's buildings, and the slippery aftermath of a Hanover snowstorm (challenging enough for the able-bodied), might legitimately question why a person with limited mobility would even want to subject himself to the rigors of a college well-known for its rugged outdoorsmanship. Brad Pagliaro '85, who, because of cerebral palsy, walks with braces, decided Dartmouth was the place for him after seeing a number of colleges throughout the Northeast. Pagliaro, who was admitted on early decision, noted, "The factor of accessibility was not part of my decision." Steve Carey '74 recalls, "I thought about. . . going to Dartmouth first then about the necessary logistics of getting around in a wheelchair." He mentions the fact that his father had gone to the College and the strength of the math department particularly in computers - as factors in his decision. Knowing many interesting alumni sparked an interest in Dartmouth for Amy Stewart '85, who also has cerebral palsy. The College's beautiful setting, the resources of nearby Mary Hitchcock Hospital, and the challenge of attending Dartmouth were what drew her here. Indeed, the reasons why most students come to Dartmouth its academic reputation, the feeling of community, the spirit, the family ties, its locale - are as appealing to the disabled as to their more able-bodied counterparts. The assumption held by some, that no handicapped person in his or her right mind would want to endure Hanover's winters, and its corollary that the College need not provide accessibility - is quite clearly fallacious.

Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 states that "no handicapped person shall be denied the benefits of, be excluded from participation in, or otherwise be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving federal financial assistance." As expected, the national reaction to federally-mandated accessibility was not always positive. University administrators and facilities planners across the country expressed the twin concerns of cost and aesthetics. Not counting the lost space, installation of an elevator in an older building can cost as much as $100,000 and renovating a rest room can easily run up to $12,000. Furthermore, images of Georgian quadrangles and stately rows punctuated by gently-sloping ramps seemed to impinge on some ideal of architectural integrity.

As a recipient of federal funds, Dartmouth had to conform to regulations set by the Health and Human Services Department of HEW to make programs accessible by 1980. Both the law and the regulations specified program, rather than architectural accessibility, thereby easing the cost and aesthetic concerns. (The regulations do, however, specify that all new construction be accessible to the handicapped.)

Through the work of the Committee on the Handicapped established by President Emeritus John G. Kemeny, a self-evaluation of program accessibility was conducted and a two-phase transition plan was developed to ensure compliance. The committee, which was chaired by Associate Dean Alvin Richard, consisted of representatives from the offices of facilities planning, dean of the faculty, personnel, admissions, legal counsel, and affirmative action as well as Richard Luplow, a quadriplegic who was teaching at the College, and Stewardship Director David Eckels '44, who is confined to a wheelchair. Much of the evaluation process involved informing College officials of the mandates of the law and forcing them to consider how they would make programs accessible. Dave Eckels remembers a faculty member who, prior to Section 504, refused to move a class from a third floor location to accommodate a student confined to a wheelchair. The student was carried up and down the two flights of stairs for each class - an experience Eckels terms "extremely frightening." In most cases rescheduling and a willingness to meet individuals at accessible locations satisfied the requirements. An awareness of barriers facing the disabled and the areas that needed immediate attention also surfaced.

The first phase of the transition plan, which in the opinion of the committee "should have been completed even without the federal regulations," was completed by the June 1980 federal deadline. Improvements, costing $93,500, included providing accessible entrances to the main floor of Baker Library, all of Thayer Hall, the Hanover Inn, the Dana-Gilman buildings, and Murdough Center. They also included the installation of handicapped rest rooms in a number of buildings and the construction of handicapped dorm facilities in Streeter and North Mass Halls.

Phase 2 of the transition plan focuses on those facilities which house programs that cannot be easily relocated and those areas where poor Accessibility could (depending on the number of handicapped students enrolled) be a problem. Proposed costs for the completion of Phase 2 would be close to $500,000. Since some of these improvements involved areas that were already slated for renovation, and others were large enough to necessitate specific fund-raising, the Trustees authorized a maximum further outlay of $187,000 to implement Phase 2 of the transition plan. Areas where Phase 2 improvements have been completed since 1980 include renovating the Fayerweathers and the first floor of the gym and substantially increasing the amount of accessible classroom and faculty office space.

While the College should be lauded for complying with the Section 504 regulations, there are areas still in need of improvement. The spirit of Section 504 is to make all new construction readily accessible to the handicapped. As Brad Pagliaro explains, "504 is not there to make it easy; it is there to make it possible." Ideally, the differently-abled and the able-bodied should be able to use facilities together rather than to have to resort to the old, more costly practice of providing special entrances, elevators, or assistance for each.

The gently-ramped main entrance of the new Hood Museum (which will also provide entry to the Hopkins Center from the Green) is exemplary in this regard. Unfortunately, the College did not improve wheelchair accessibility to Spaulding Auditorium which houses so many public events at the time of the Hood Museum construction. Imagine for a moment that you are confined to a wheelchair and you want to hear the Concord String Quartet in Spaulding. Although Spaulding does have a ramped entrance, to use it, you must pass through the Courtyard Cafe, head outside, and come back in at the lobby, which is frequently crowded. Since there is no specific wheelchair seating in Spaulding, you would probably have to move into one of the fixed seats during the performance. Using the Hop's only accessible rest room during intermission would require an additional trip outside, taking the elevator down one flight, wheeling to the opposite end of the Lower Jewett Corridor, and then returning along the same route.

The new Rockefeller Center provides a beautifully-bricked ramp located at the least-used entrance; unfortunately, it is also quite a distance from either handicapped parking or the lovely Golding Courtyard. Access to the ramp is available via a gravel path or by traversing a path of cobblesized stones placed about four inches apart. Neither approach is easily negotiated if you're making the trip by wheelchair. Fortunately, the Rockefeller Center provides an elevator to all four floors of Silsby, and the new Center is fully usable by hearing-, sight-, or mobility-impaired people. There are also conveniently accessible rest rooms and adequate space for wheelchairs in the fixed-seating classrooms.

At Baker Library, accessibility to the main floor was provided by installing a ramped entrance to the 1902 Room. But this entrance still does not enable you in your wheelchair to enter the library unassisted. When one of the double doors leading into the room is open, there is less than the 32-inch width required for wheelchairs, and the other door has closed stops at the top and bottom of its seven-foot height. The transition plan recommendation to provide a ramp to the front revolving door and replace it with a balanced door would provide much less disruption for those studying in the library.

While the cost of modifying some structures remains prohibitive, there are areas so integral to the life of the College that ignoring them seems unthinkable. As home to many of the College's most active student organizations, most notably The Dartmouth, WDCR and WFRD-FM, and the Outing Club, Robinson Hall is undoubtedly the administration row building most frequented by students. Plans to locate an elevator in Robinson and provide a bridge to the second floor of College Hall have been under discussion for some time. In 1979, the Trustees chose to make this project a special Campaign for Dartmouth opportunity due to the anticipated $200,000 cost and the limited number of mobilityimpaired students. As of.yet, the

challenge goes unmet. In addition to making the major student organizations accessible, this project would provide easy access to the offices of Career and Employment Services, Pre-Professional and Graduate Advising, and perhaps most importantly, the Reading and Study Skills Center, the office that provides auxiliary aids for handicapped students. Also targeted for improvement are the rooms where visiting lecturers traditionally speak- 105 Dartmouth, Cook Auditorium, and 13 Carpenter. Of the three, only Cook can be reached without negotiating a flight of stairs - and all three' have fixed seating.

According to Pagliaro, there are many places where creating a level space, rather than a step, just outside a door would improve accessibility a great deal. "Dartmouth Hall is impossible, Baker Library's stairs and revolving doors are tough; there are, in short, many nightmare places." While Pagliaro is strong in his opinions, he readily admits, "I am not an activist. I just deal with whatever I'm confronted with. Regardless, I can be comfortable here."

Despite the fact that a number of physically handicapped students have attended Dartmouth over the last few years, many people still wonder about the advisability of making the campus more accessible since snow and ice can appear in Hanover anytime from October to May. Admittedly, winters in Hanover are difficult, yet the Dartmouth Plan offers students the option of being away from the College in the winter. Conceivably, a mobility-impaired undergraduate could participate in the College's Exchange Program and spend a winter at the University of California at San Diego, which provides excellent resources for the handicapped, including transportation around the campus.

While making provisions for a large number of differently-abled students makes sense in a sunny climate like San Diego, it is not only the Sunbelt schools that have made these commitments. Michigan State, with a climate similar to Dartmouth's, has become, known as a haven for large groups of handicapped students, as has the relatively new (and therefore barrier-free) Southwest State University in chilly Marshall, Minn., where five percent of the student enrollment is disabled. Ivy rival Cornell provides an office for disabled students as well as a campus map indicating handicapped parking, entrances, and appropriate paths for traversing the campus.

So it is not simply snow and ice that confront the disabled. There are barriers everywhere. As Amy Stewart explains, "Dartmouth is aware of what it needs to do on a small scale such as person-to-person interaction and the large scale such as renovations; it is the intermediate level that seems missing." She notes that professors and deans who can easily understand why she might be late to class don't necessarily have enough faith in her integrity to understand why she sometimes requests additional time for taking exams or completing coursework. Stating that it frequently takes her four times as long as other students to complete reserve readings or research a term paper, Stewart readily admits, "It's been tough." Just as quickly she acknowledges that there are individuals here who have been "phenomenal" in the personal attention they have provided. Stewart says, "The positive human touches at Dartmouth far outweigh the mechanical loss."

Providing accessible spaces does not benefit only the disabled. Since the early 19705, the 1944 Class Project has been the installation of handrails along steps at most major campus buildings. Spurred on by Dave Eckels, who was walking with the use of crutches at the time, the Class contributed $10,000 until 1978, when the scope of the College's commitment to accessibility exceeded 1944's project budget. The availability of handrails has also provided welcome assistance to students temporarily on crutches and to numerous visitors for whom getting around is or has gotten to be a problem. And as any parent of a strollerage toddler can attest, ramps provide relief to more than wheelchair users. Of course, Dartmouth's commitment to "educate men and women who have a high potential for making a significant positive impact on society" does not apply only to the able-bodied. Indeed, as the disabled live increasingly independent lives, it is essential that institutions such as Dartmouth help them achieve their goals. The added diversity and perspective of the disabled as students, faculty, and employees enrich the entire community.

Furthermore, since the College has both a legal and a moral responsibility to ensure accessibility to all programs, handicapped individuals should not need to become activists in addition to their roles as students or employees. One step in the education of the community vis-a-vis equal access for the handicapped will involve the Affirmative Action Office, which will be reviewing accessibility for new facilities. As the campus becomes more accessible, perhaps more handicapped young men and women from all parts of the country will feel that Dartmouth is the school for them.

Diploma in hand, a determined Brad Pagiaro '85 makes his way down the steps atgraduation.

Dave Eckels '44 enjoys working out on thetrack at Memorial Field when weatherpermits, that is.

Indeed, the reasons whymost students come toDartmouth - itsacademic reputation, thefeeling of community, thespirit, the family ties, thelocale - are as appealingto the disabled as to theirmore able-bodiedcounterparts.

As Brad Pagliaro '85explains, "504 is not thereto make it easy; it is thereto make it possible."

While the cost of modifying some structures remainsprohibitive, there are areas so integral to the life of theCollege that ignoring them seems unthinkable.

So it is not simply snowand ice that confront thedisabled. There arebarriers everywhere.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureOn the Air

December 1985 By Michael Berg '82 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryTranslating Plato's Republic

December 1985 By Kathie Min -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Century of Translation

December 1985 By WILLIAM C. SCOTT -

Cover Story

Cover StoryFragments of papyrus

December 1985 By RICHARD W. STERLING -

Article

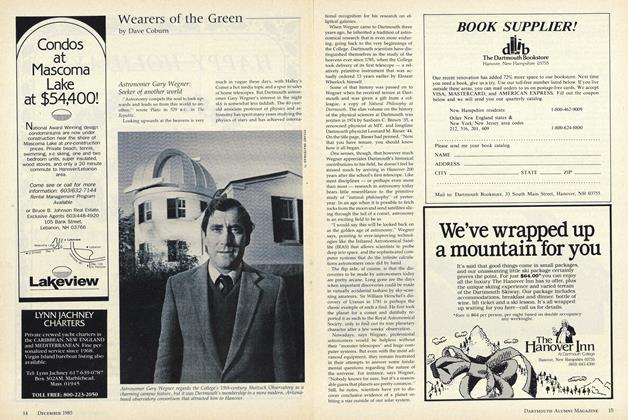

ArticleAstronomer Gary Wegner: Seeker of another world

December 1985 By Dave Coburn -

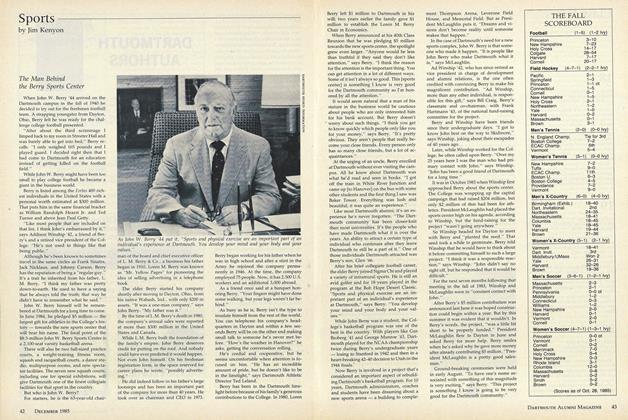

Sports

SportsThe Man Behind the Berry Sports Center

December 1985 By Jim Kenyon

Nancy Wasserman '77

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorOn Wise Teachers

February 1992 -

Feature

FeatureExtra Credits & Bonus Points

April 1980 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Article

ArticleWearers of the Green

OCTOBER 1981 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Article

ArticleToys in the Office

MARCH 1982 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Feature

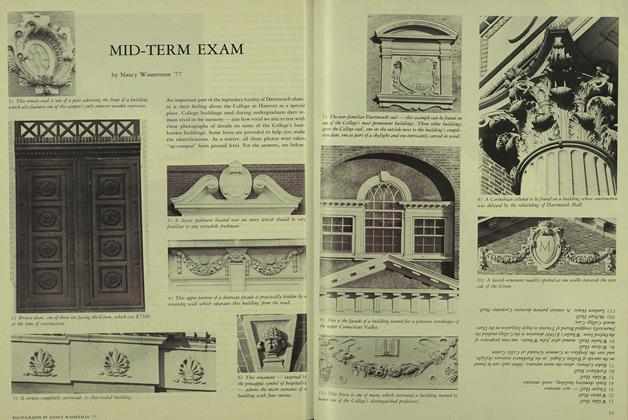

FeatureMID-TERM EXAM

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1983 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Article

ArticlePhilosopher Coach

MARCH 1983 By Nancy Wasserman '77

Features

-

Feature

FeatureVincent Jones 52 Heads Alumni Council

JULY 1972 -

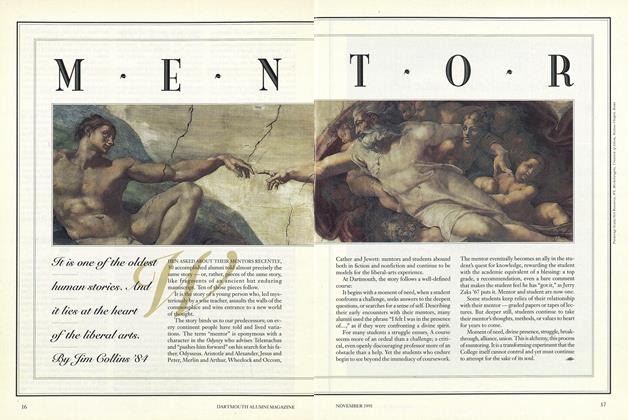

Cover Story

Cover StoryMENTOR

NOVEMBER 1991 By Jim Collins '84 -

Features

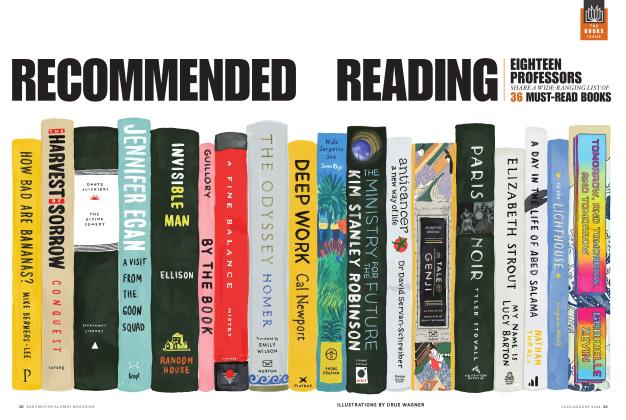

FeaturesRecommended Reading

JULY | AUGUST 2024 By Joanna Jou '26, Caroline Mahony '25, Heya Shah '26, 1 more ... -

Feature

Feature"Little Joe" Wentworth, 1900: Scholar, Athlete, Gentleman

OCTOBER 1984 By John F. Anderson '34 -

Feature

FeatureSenior Valedictory

JULY 1972 By ROSS P. KINDERMANN '72 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

July/August 2005 By Thomas Vieth '80