The issue of alcohol at Dartmouth seems to be perennial; it is usually discussed at great length within the Dartmouth family. This fall the issue was placed in the context of the world at large, raising questions of the individual's responsibility to that world and to himself. A conflict was inevitable as the somewhat insular atmosphere of the College faced the country's preoccupation with sweeping alcohol reform. The drinking age has never permeated campus consciousness; we've never felt it applied to us. As Dean Shanahan wrote this fall in his Letter on Alcohol: "Dartmouth has traditionally focused much more on dealing with alcohol-related behavior than it has on specific age limitations." "Be 21 or be gone" is a product of the world beyond the Green, or so it seemed in our illegal Xanadu.

Another factor adding to the Never Never Land quality of bur existence is the age of those who inhabit it. Between 18 and 21 lies a kind of world unto itself. One has the right to die for one's country and to be tried in a court of law as an adult, but in New Hampshire at least, one cannot order a white wine spritzer or a gin and tonic. However persuasive the statistics behind the laws, certain absurdities remain. Indeed, the same sort of well-intentioned logic has produced laws which make bartenders and hosts responsible for the actions of those whom they serve, so that monitoring the sobriety of one's guests is no longer simply a question of taste, but in some quarters, a legal necessity.

The issue took on new dimensions for us at Dartmouth this October when several underage Smith students drove to Hanover, attended a couple of fraternity parties, and crashed on their way home. Sadly, one young undergraduate lost her life in the accident.

In the aftermath of the tragedy, the campus reverberated with speculation that house presidents and social chairs would be held personally liable. The College, meanwhile, has taken a fairly equivocal stance, stating simply that students are subject to state laws. New Hampshire state laws have followed the national trend of the so-called "dram-shop liability," a principle originally aimed at bars and restaurants that served intoxicating liquors to their patrons, now being interpreted to include private hosts that do the same.

Dartmouth's alcohol policy is beginning to reflect a perception that the server bears at least some responsibility for the overindulgence of those served. Passing judgment upon the relative sobriety of others has become a Dartmouth reality with the institution of party monitors. As it now Stands, any group sponsoring a party must supply one student monitor for every twenty guests. Unfortunately, party monitors, who are responsible for keeping watch on the proceedings, may be forced to ask their peers to stop drinking or to vacate the premises. Monitors become, in essence, their brothers' keepers. Their presence extends the burden of responsibility from the individual to the institution, thus implying that community control supercedes self-control.

Yet the concept of community control runs counter to the Dartmouth Principle of Community, which states in part, "The life and work of a Dartmouth student should be based on integrity, responsibility, and consideration." In order to maintain our special community, Dartmouth students are required to take responsibility for themselves. We depend on each other and on our College, but rely on ourselves. Our responsibility lies in maintaining a commu- nity of individuals; our privilege is to live in that community.

The decisions we make about alcohol do affect the community at large, as the death of one so young brought home. But the decisions, along with their repercussions, are -or at least should be the responsibility of the individual making them. In his essay "Self-Reliance," Emerson writes "There is a time in every man's education when he arrives at the conviction that envy is ignorance, that imitation is suicide; that he must take himself for better for worse as his portion." As undergraduates, indeed, as human beings, we can make a multitude of wrong choices about many things, including alcohol consumption. The consequences, for better for worse, are the individual's alone. Spreading the blame invalidates the principle of self-reliance that is so central to our much-prized liberal education.

Marlea Clark, a senior from Jamestown, N.Y.,is an English major. She enjoys jogging in theearly morning, Chaucer, and fine French wine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureOn the Air

December 1985 By Michael Berg '82 -

Feature

FeatureThe Impact of Section 504

December 1985 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryTranslating Plato's Republic

December 1985 By Kathie Min -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Century of Translation

December 1985 By WILLIAM C. SCOTT -

Cover Story

Cover StoryFragments of papyrus

December 1985 By RICHARD W. STERLING -

Article

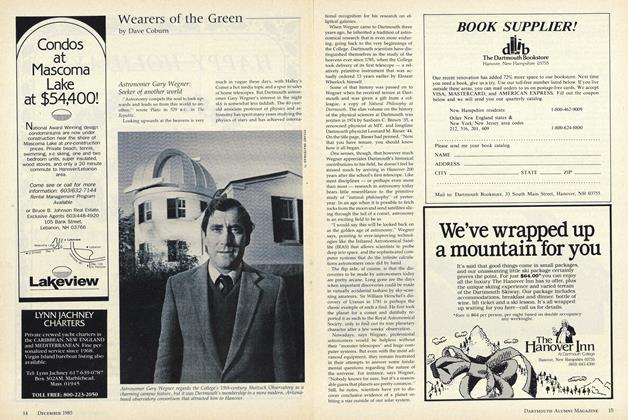

ArticleAstronomer Gary Wegner: Seeker of another world

December 1985 By Dave Coburn