This Man Scanndalized Eleazar Wheelock, DODGED his creditors, dropped OUT of college, INFURIATED Catherine Great, DIED vomiting on the shores of the Nile River... ...and continues to INSPIRE students to THIS day. cularly BAD luck on a global scale is why so FEW others remember Jonh Ledyard.

He arrived out of the woods like some gaudy apparition.

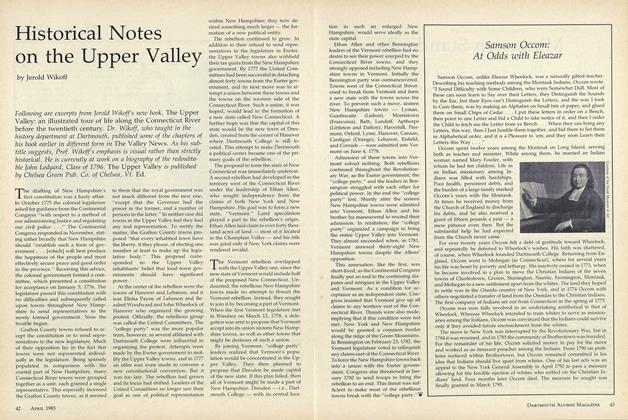

It was April of 1772, on the tail end of an especially bad mud season in New Hampshire. The state's few roads a euphemism, even in the best of times, for these tracks through the forest were little more than oozing ruts. The only road anywhere near Hanover lay almost a mile from campus. John Ledyard, a freshman in the class of 1776, had traveled almost 200 miles from his home in Hart- ford, Connecticut, to Dartmouth College, an earnest assemblage of log huts and planked buildings 40 miles beyond the last frontier outpost. The College was an austere place with an even more austere purpose: to train missionaries who would spread "Christian Knowledge among the Savages of [the] American Wilderness," as the founder, Eleazar Wheelock, put it. The curriculum centered on religious instruction. The rigid daily routines, the harsh rules, the students' very attire expressed piety and obedience. And into the middle of this scene came John Ledyard. He was driving a fashionable horse-drawn sulky and wearing huge, baggy Turkish pantaloons. The campus was amazed.

The breeches were startling enough. In addition, Ledyard's collar lay open so that people could actually see bare neck; a neckcloth was nowhere to be seen. Then there was the sulky. How on earth did he get it over the bridgeless rivers? How did he drive it, alone, through the dense forest into Hanover? Why was the sulky loaded with, of all things, stage props and curtain material for theatrical productions? This was the front line for the Great Awakening. Dartmouth students didn't do theater. Ledyard's schoolmates were to talk about his arrival for the rest of their lives, searching for the right way to describe his remarkable appearance. After much thought a fellow freshman, Wheelock's 14-year-old son James, brought up just the word. "Singular," said Wheelock fils. The man was quite... "singular. "

Tow-headed John Ledyard, a man of style who would arrive at impressive destinations (if he arrived at all) in singular fashion, was to become one of the world's most spectacularly unsuccessful explorers. He was to cover more territory than anyone else of his time; and yet he almost never arrived where he intended. He died young, after an attempt to explore the American West 16 years before Lewis and Clark. He had watched Hawaiians kill Captain Cook, had walked through the Nordic wilderness in midwinter, befriended Thomas Jefferson and John Paul Jones, and earned the enmity of Catherine the Great. He could have become one of the best-known explorers of all time, but he is remembered by few people outside of Dartmouth, and people at Dartmouth remember him mostly for yet another failed destination: graduation. This is the story of why he left the College, and the arduous paths that led him to die, painfully and ignominiously, on the shores of the Nile River. It is the story of "one of Dartmouth's greatest sons, and one of the unluckiest characters in American history.

His mother, apparently, had wanted him to be a missonary, which explains why such a remarkably unsuitable character showed up on the Hanover Plain. Just weeks before he set off for Dartmouth at the age of 20, Ledyard wrote his Aunt Betsy disparaging remarks about Christ's crucifixion ("Ungenteel entertainment," he called it), the New Testament ("tasteless repasts"), and all of Christianity ("Faith, regeneration, repentance, & whats worse than all Humility."). Not surprisingly, when Ledyard arrived on campus, it and his manners (not to mention his pants) clashed. His one year at the College was more notable for various escapades than for academic achievement. Among other things, there was the conch-shell incident. Each of the 12 freshmen was supposed to take a turn blowing a conch to call students to prayer and class. When it was Ledyard's turn, he performed the duty with exaggerated reluctance. Even worse, his fellow students loved the performance. On at least one occasion he had the temerity to swear loudly in class, after a student put a cold iron wedge down his back. Along with a few other students he taunted President Wheelock, requesting that "stepping the Minuet and learning the use of the Sword" be made a part of the curriculum. He put on a fake beard and conducted a tragedy by Cato, taking a lead role as a Numidian prince. Then, late that summer, after only four months at Dartmouth, he disappeared.

He seems to have gone AWOL to spend a couple of months with the St. Francis Indians near the Canadian border. He returned to campus in late November with a smattering of the Indian tongue and an evident distaste for the missionary life. In the middle of that winter, this time with Wheelock's permission, he led a group of students on an overnight expedition to Velvet Rocks. The group, including James Wheelock, spent a sleepless night on pine boughs, returning in time for morning prayer.

The other students doubtless had little desire to repeat the performance. Ledyard was different. Although of average height for the period, he was broad-chested and possessed remarkable stamina.

The episode was a taste of things to come: theatricality combined with a startling physical feat. It was a performance he was to repeat many times in his short life. The next one entailed his departure from Dartmouth.

Exactly one year after he arrived, Ledyard absconded in the grandiose manner that has become part of his legend. He felled a large tree, and with the help of several other students fashioned a canoe some 50 feet long and three feet wide. When the crude vessel was finally launched, Ledyard simply floated downstream while conspicuously reading one of the two books he carried with him Ovid and the Greek Testament.

The image of the hand-hewn canoe drifting from sight into an overgrown wilderness, its solitary occupant reading classical verse, cast a lasting spell over the adolescents who watched from shore. Over the years, that same romantic vision of the departure from Dartmouth has come to be an accepted part of the Ledyard lore. Why he actually left the College was never asked.

The story of Ledyard has been retold numerous times, but the many narrations have invariably been recastings of a nineteenth-century biography by Jared Sparks. Sparks was oddly quiet about the reasons for Ledyard's premature departure from Dartmouth, and subsequent biographers have more or less followed suit. The truth is, Ledyard quit Dartmouth because he had squandered an inheritance of 60 pounds bequeathed him by his grandfather. That small legacy was meant to pay for four years of college. Where Ledyard might have spent so much money in so few months is not known, but records of his debts show that he was well acquainted with a disreputable local tavern owned by a thorn in Wheelock's side named John Payne. Ledyard probably bought drinks for himself and his fellow students (including, undoubtedly, Eleazar Wheelock's sons, who themselves frequented the establishment). With considerable dramatic flair, Ledyard then transformed what could have been a disgraceful expulsion from college into a wondrous adventure at least, in the eyes of generations of Dartmouth students.

His family saw something else. When he pulled his canoe out of the river at Hartford, they simply thought it one more prank by an undisciplined son. The family had already undertaken unsuccessful efforts to train Ledyard as a merchant and a lawyer. His failure to prepare at Dartmouth as a missionary added yet another profession to the list of unsuitable occupations. His arrival in Hartford also brought considerable embarrassment. Along with an unfinished education, he had left behind some unpaid bills. Ledyard's exasperated family made one last effort to secure him a respectable position in society. Within a month after his return home, he was sent to the nearby town of Preston, Connecticut, to seek the guidance of two ministers. Despite the dismal failure at Dartmouth, the family still anchored its hopes for Ledyard in the ministry. Predictably, that plan, too, quickly miscarried. Left with no future prospects, he took to sea.

Late in 1773, Ledyard shipped out as a common sailor aboard a vessel bound for Gibraltar. For a young man out of work on the New England coast, the decision was almost inevitable. Men in their early 20s who could find no other employment accounted for a substantial number of seamen aboard American ships. When Ledyard returned to Connecticut some nine or ten months later, he continued work as a sailor, shipping out to Boston and other New England ports. Whenever back in Connecticut, he traveled to Stonington to court a woman he identified only by the initials "R. E." Freed at last from family efforts to determine his future, Ledyard seemed content to drift into the life of a sailor and to contemplate marriage. He might well have settled down in Connecticut, had something not happened that changed his entire life.

In march 1775, Ledyard shipped out from New York in a merchant ship bound for Falmouth, England. His hope making the voyage was to earn more money than he did in working the New England coastal trade. But in England he was promptly taken prisoner by a press gang and given a choice: either ship for the coast of Guinea or join the British army. Keenly aware of the harsh conditions on many British vessels, Ledyard opted for the military. A month later the American Revolutionary War began.

According to official records, Ledyard entered the British military as a corporal in the 24th Company of Marines, Plymouth Division, on July 15, 1775. He served without incident for about six months until early in 1776, when he was ordered to Boston to fight his countrymen. By then, Britain had begun a massive buildup of troops for a military expedition to bring a quick end to the American rebellion, and Ledyard's division was among those assigned to the campaign. Ledyard asked to be given some other duty. Permission was granted.

Timing was crucial to the military's willingness to honor Ledyard's request. Soon after Ledyard made known his refusal to fight against fellow Americans, Captain James Cook agreed to lead a third voyage of discovery to the Pacific. The trip was expected to take three years, and volunteers were scarce. Ledyard was attached to the expedition as a corporal of the marines.

The ship Resolution was to sail to the Cape of Good Hope and on to Australia, then to Tahiti and northward to the North American coast to search for a northwest passage through the American continent. The voyage would end unsuccessfully after more than four years. No passageway could be found through the ice that met Cook and his two ships in the Arctic Ocean. The one new discovery for Europe was Hawaii, where Cook was killed in a confrontation with the natives.

But for Ledyard, the voyage would transform his life. In the spring of 1778, while American colonists on the Atlantic coast continued to fight their war for independence, Ledyard became the first white American to set foot on the western coast of North America when Cook's ships anchored for several weeks on Vancouver Island. Ledyard and other crew members traded for the fur of 1,500 sea otters, beavers, seals, and bears. On the voyage home they sold many of these furs at astronomical prices in Canton. The lesson was not lost on Ledyard: fortunes could be made by carrying furs from the American Northwest to China.

When the voyage ended in. London in October 1780, Ledyard was ordered to return to active duty in the British military. For a year he was stationed at Plymouth, where he performed the routine tasks and drills of a soldier. Then in October 1781 he was shipped out to the American colonies. That same month, Cornwallis surrendered his entire army at Yorktown, Virginia, effectively bringing the War of Independence to an end. Ledyard was again spared having to fire on his fellow countrymen. The peace also made it easier for him to desert his ship, which he did some months after his frigate assumed its post along Long Island.

I Sometime in the autumn of 1782, Ledyard returned home to Hartford, where for the next several months he rewrote a journal he had kept of Cook's voyage. Of far more interest to him, however, was a plan to return to the Pacific coast. His scheme was to establish an American fur-trading post on the northwest coast more than 20 years before John Jacob Astor founded Astoria at the mouth of the Columbia River.

In mid-April of 1783, George Washington issued general orders declaring a cessation of all hostilities between America and Great Britain. A final treaty was not signed until seven months later, but for all practical purposes the Revolutionary War had ended. For Ledyard, the time had come to act. Leaving Connecticut, he traveled to New York in an attempt to find a partner willing to sail for the Pacific. His plan sounded farfetched to many American merchants, most of whom had engaged in nothing more than trade to the West Indies or, at most, a transatlantic voyage to Europe. The sorry state of most American vessels at the end of the war deterred others from underwriting such a far-ranging venture.

Ledyard made his way down the coast, meeting with repeated rejection. His fortunes changed in Philadelphia. Robert Morris, who was America's most prominent businessman, agreed to finance Ledyard's voyage to the Pacific. He would be gone two or three years, Ledyard wrote his mother, but if he were successful, he would no longer "have occasion to absent myself any more from my friends."

But this venture, too, ended in failure. Morris backed out of the deal, citing financial difficulties. Despondent, Ledyard fell ill for several weeks. In the summer of 1784 he sailed for Europe to seek a backer in France. He never saw America again.

Incredibly, within days after his arrival in France Ledyard found a group of merchants in the coastal town of Lorient willing to back his expedition. The voyage was to begin the following summer, after two or three ships were well-outfitted. Until the departure, Ledyard was to remain in Lorient, to be provided for "genteely" by the merchants. Success again seemed imminent. But at the last moment the voyage was canceled, the financiers backing out. Ledyard traveled to Paris, where he made contact with John Paul Jones. Jones, who was in France negotiating for money owed Americans for the capture and sale of British vessels during the Revolutionary War, was intrigued by Ledyard's proposal and promptly agreed to finance the sailing of one or two ships to the Pacific. But the same pattern continued. Jones failed to find a suitable vessel for the voyage and within months the project folded.

Of course, Ledyard could have returned to America when it became clear that he would find no backing in Europe. Had he persisted, he might have returned home to seek a more modest way to participate in the Northwest fur trade. He might still have earned his fortune. But fortune alone was not what he was after. He simply abandoned the idea and turned to something far more grand.

The idea came from America's minister to France, Thomas Jefferson. The two men had met shortly after Ledyard's arrival in Paris, but they had had no regular contact until the first months of 1786, after Ledyard abandoned his proposed trading venture with Jones. And then, quite abruptly, Jefferson became the dominant force in Ledyard's life.

For the next several months, Jefferson helped to support Ledyard financially not out of disinterested benevolence but because Jefferson had great plans for the young explorer. Almost from the moment of American union, Jefferson privately advocated a policy of westward expansion. In Ledyard he saw the possibility of exploring half of the North American continent. Jefferson suggested that Ledyard set out on an expedition to walk from the West Coast to Connecticut. First he would have to reach the Pacific Northwest by traveling from Paris to Russia and across Siberia.

Despite the fantastic nature of Jefferson's proposal, Ledyard agreed to it without hesitation. It was nothing if not dramatic, and Ledyard liked his ventures to be dramatic. He was eager to set out from Paris within days, but Jefferson persuaded him to wait until he received official permission to cross Siberia. Russia required passports for foreign travelers, the only country other than Turkey with such a law prior to World War I. The delay caused Ledyard considerable anxiety. Too often, interminable waiting had led to failure. Toward the end of the summer of 1786, he could wait no longer. Still not knowing whether he would receive permission to cross Siberia, he traveled to London, where he was told a vessel was about to set sail for the American Northwest. But the Fates were against him. He boarded the ship, only to watch as customs officials seized and impounded the vessel before it could descend the Thames. When Ledyard next heard from Jefferson, he learned that Empress Catherine had denied him permission to enter Siberia. Unknown to other European countries, Russia had extended its empire to Alaska, where it carried on a highly profitable fur trade. Catherine had no desire to allow a stranger into the region.

The news from Jefferson did not deter Ledyard. Convinced that he could obtain a passport on his own in Russia, he set out, as he put in a letter to a cousin, "as an American Citizen to the courts of Petersburg Moscow Tobolskoi, Jenenskoi Obiskoi Bolcheretskoi, Kamschatka, Nootka Origon Naudowessie Chippeway &c farewell." And thus began what he hoped would be his "passage to glory."

Leaving England in December of 1786, Ledyard sailed for the city of Hamburg in northern Germany. The passage was not pleasant "I was out in [the Elbe] forty hours in an open Boat," he wrote to a friend but the voyage was to be the easiest part of his journey. From Hamburg he walked north to Copenhagen and then on to Stockholm, reaching the Swedish capital around the middle of January 1787. From Stockholm the normal route to St. Petersburg was across the Gulf of Bothnia, either by ship in the summer or by sledges drawn across the ice in the winter. But that winter the water had not frozen. Ledyard was forced to travel north around the gulf—a distance of more than a thousand miles to gain no more than the hundred miles across the water.

Ledyard traveled on foot through a frozen landscape of snow and ice, averaging some 20 miles a day. His 1,200-mile trek from Stockholm around the Gulf of Bothnia to St. Petersburg lasted two months. His daily pace was not astounding in itself, although the number of weeks he maintained the same progress revealed tremendous stamina. What made the journey truly remarkable were the conditions. Winter temperatures in the region could reach as low as minus-60 degrees Fahrenheit, and sudden snowstorms could trap and kill anyone caught outside of shelter. He lost all his baggage, and his dog died. Ledyard himself recorded no details of the trek, but Thomas Jefferson wrote of the hapless explorer: "...having no money they kick him from place to place and thus he expects to be kicked around the globe." The comment was to be prophetic.

In st. petersburg Ledyard learned that Empress Catherine was not in the capital. She had departed in early January on her famous tour of the Crimea arranged by Potemkin. Ledyard applied to the British and French embassies for assistance in obtaining a passport but was rebuffed by both. Finally, after two months, he succeeded in getting an officer attached to the entourage of the Grand Duke Paul, Catherine's son, to help him obtain travel documents.

On June 1, 1787, Ledyard set out from St. Petersburg. He did not walk across Russia and Siberia, as is commonly believed, but instead traveled in a postal coach called a kibitka. As Ledyard had learned from his trek through the Nordic wilderness, travel on foot "is ridiculous in this country." The land was simply too vast and sparsely settled to be walked quickly. His hope was to gain the North American continent as soon as possible, where his real exploration was to begin. Although relatively speedy, travel by kibitka was far from luxurious. The roads were exceedingly rough, and passengers often suffered spinal injuries from the tossing and shaking. Still, by July 23, Ledyard had reached the Siberian town of Barnaul some 3,500 miles from St. Petersburg, and almost half the distance to Okhotsk on the western coast of Siberia. In his diary he expressed hope that he might reach the Kamchatka peninsula by early September. With luck he could catch a Russian fur-trading vessel to Alaska and be on the North American continent before winter. For the first time since his departure from St. Petersburg, Ledyard's spirits were high. He wrote in his journal on the landscape, the weather, geological formations, and the customs of the people. Noting repeatedly that the native Siberian peoples were similar in appearance to and shared many customs with American Indians, Ledyard concluded that a migration from Asia led to the original inhabitation of the Americas. "Sir," he wrote to Jefferson, "I am certain that all the people you call red people on the continent of America & on the continents of Europe & Asia as far south as the southern parts of China are all one people by whatever names distinguished & that the best general one would be Tartar." Today, such a conclusion seems remarkably prescient, given that in the eighteenth century it was generally believed that Native Americans were descendants of the ten lost tribes of Israel.

The journey across Siberia continued, but Ledyard's hope to reach the coast by mid-September soon vanished. By mid-August he had reached the settlement of Irkutsk, where he made the acquaintance of a couple of Russian businessmen. His journey across Siberia was two-thirds complete, but the most difficult passage lay ahead. Beyond Irkutsk, travel by kibitka ended, and a 1,500-mile journey began down the Lena River to the settlement of Yakutsk. From there to Okhotsk was another 700 miles over the Stanovoi Mountains, which were so rugged that passage was possible only in a well-supplied expedition.

Ledyard reached Yakutsk by September 18, only to learn that it was too late in the season to cross the Stanovoi Mountains. For the third time he was stopped by winter. But an even worse foe awaited him. Unknown to Ledyard, one of the merchants in Irkutsk had sent a message to St. Petersburg inquiring why a foreigner had been permitted to observe the Siberian fur trade. Empress Catherine, upon learning that Ledyard was in Siberia, became furious. Unaware that Ledyard had been granted a passport and believing him to be a spy for the French government, she immediately ordered his arrest. The order reached Irkutsk in February, where Ledyard had returned to spend the winter. He was promptly arrested, placed in a kibitka. and driven off into the night with two guards. For almost a month, Ledyard was carried night and day over the frozen roads of Siberia to Moscow. He was given little to eat, and his health suffered considerably. In Moscow he was briefly interrogated and then banished. Soldiers took him to the Polish border, where they arranged his passage to the sea. Ledyard sailed to England, reaching London at the beginning of May 1788. After a journey of more than 14,000 miles and 17 months, he was back where he had started.

Then for one brief, last moment, it appeared that Ledyard's luck had changed. Within weeks after his arrival in London he was recruited by a newly formed scientific association to search for the source of the Niger River. The chance to make a name for himself still seemed possible. But Ledyard's African exploration reached no farther than Cairo. Civil strife and poor weather prevented him from carrying out a plan to follow the Nile southward. In January of 1789 he attempted to treat himself for an illness—depression, possibly. Ledyard had been given a hasty introduction to medicine while in England to help him cope with disease and sickness in the African interior. Those few lessons proved disastrous. He gave himself too strong a dose of an emetic and died six days later, vomiting so violently that a blood vessel burst in his brain. He was barely 37 years old.

IF JUDGED BY NOTHING more than the results of his explorations, Ledyard was unquestionably a failure. Yet there is something about his life that cannot be so easily dismissed. If nothing else, he probably saw more of the world than did any of his contemporaries. Others might have traveled farther, but their journeys were usually confined to the oceans and coasts. Ledyard journeyed inland in an age when overland travel was exceedingly difficult. He was in the South Pacific, Europe, Asia, North America. He even explored inland some of Alaska and Hawaii while on his voyage with Cook.

The real fascination with Ledyard, however, is not where he went but what he attempted. If he had managed to regain the northwest coast of America, he might well have succeeded in making his way to the Eastern Seaboard. He was acquainted with Native Americans and had considerable sympathy for their culture. He might have passed safely from one tribal region to another. If only the ship had not been seized in London. If only Empress Catherine's arrest orders had been sent three months later. If only, if 0n1y... Ledyard would be universally remembered today as the man who in the eighteenth century traveled around the world by land. His name would be in every history book.

Ledyard's particular love was the theatrical and the dramatic, and it is perhaps best to judge him in those terms. When Ledyard set out on his trek across Siberia toward the North American continent, he was aware of the dramatic impact his journey would make. Suddenly, unexpectedly, he would appear out of the wilderness to tell a tale scarcely believable. His life itself would be the drama.

Ledyard was fated instead to play a tragic role. Still, the performance was brilliant.

Ledyard did his disappearing act exactly one year after he arrived.

Jefferson suggested that Ledyard set out on an expedition to WALK from the West Coast to CONNECTICUT.

Believing him to be a SPY for the French government, Catherine immediately Ordered his ARREST.

Jerold Wikoff is editor of Gettysburg College's alumni magazine. He is writing a book about. John Ledyard based on new research.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTHE PEMI AFFAIR

June 1993 By KIRK SIEGEL'82 -

Feature

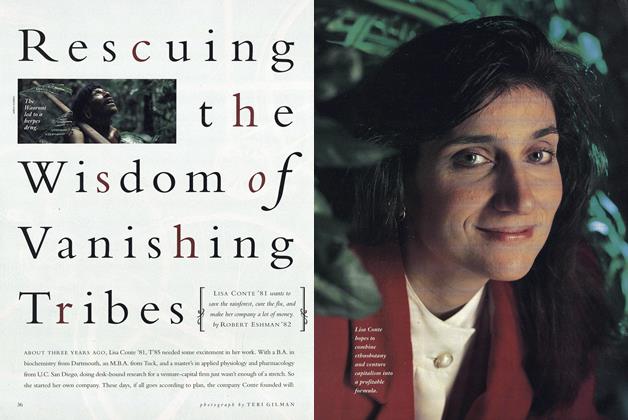

FeatureRescuing the Wisdom of Vanishing Tribes

June 1993 By Robert Eshman '82 -

Feature

FeatureTrip to the sea

June 1993 By Will Lange -

Feature

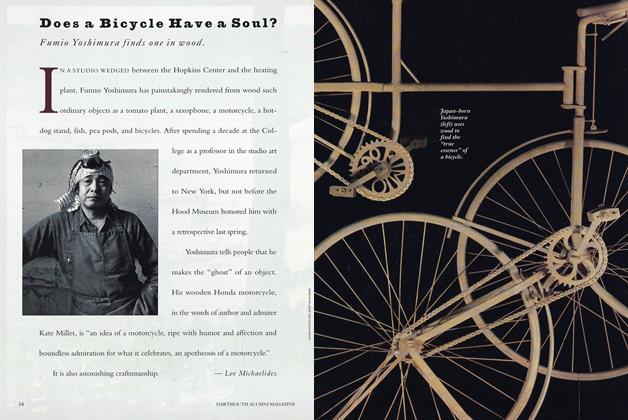

FeatureDoes a Bicycle Have a Soul?

June 1993 By Lee Michaelides -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

June 1993 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

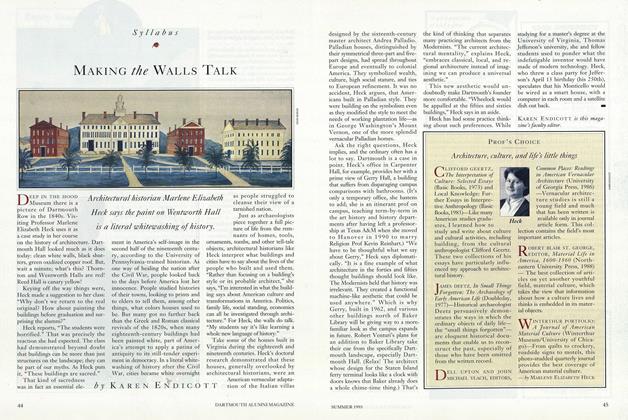

ArticleMaking the Walls Talk

June 1993 By Karen Endicott

Features

-

Feature

FeatureIt Was Summer, Yes, But Quiet... NO

October 1961 -

Feature

FeatureCOOPERSTEIN

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Brad M. Hutensky '84 -

Feature

FeatureScions of Rhodes

JAN./FEB. 1978 By Daniela Weiser-Varon -

Features

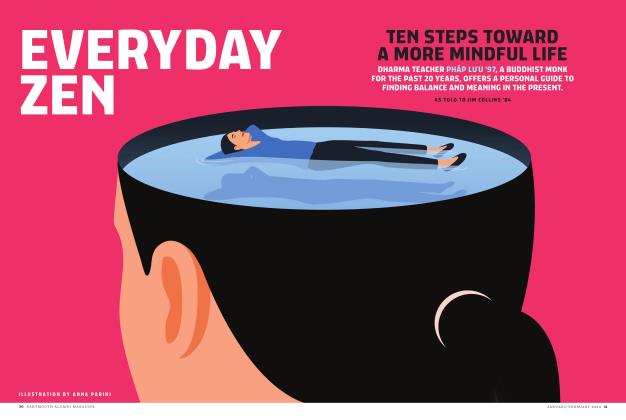

FeaturesEveryday Zen

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2024 By JIM COLLINS ’84 -

Feature

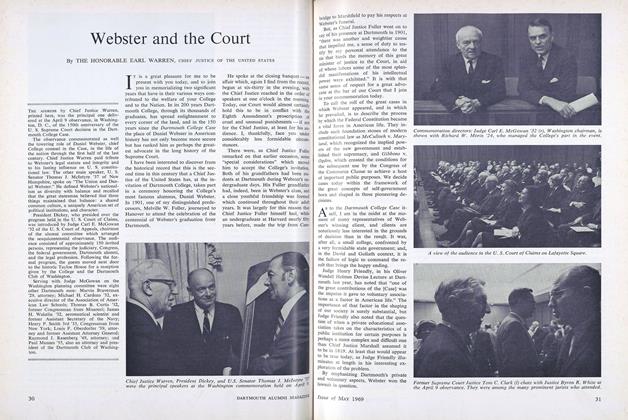

FeatureWebster and the Court

MAY 1969 By THE HONORABLE EARL WARREN -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Medical Opportunity

October 1960 By WARD DARLEY