The Thayer School of Engineering has received a five-year, $7.2 million grant, given by the Office of Naval Research, to begin a new research program this fall in arctic iceocean dynamics and mechanics. The grant is the largest research award ever given to Dartmouth.

Most of the research will take place at Thayer School, but it will involve several expeditions to Alaska and Greenland to collect ice samples and to perform tests. Dartmouth will subcontract about $1.8 million of the total grant to the University of Colorado for related studies.

The principal investigator for the arctic research program is William D. Hibler III, who joined the Thayer faculty in September as research professor of engineering. Erland M. Schulson, professor of engineering and director of the Ice Research Laboratory at Thayer, is co-principal investigator. Hibler will direct the studies of large-scale geophysical features of the region, such as the effects of wind and ocean currents on ice in regions from one to a thousand or more square miles. Schulson will direct research on small-scale micromechanics of sea ice, such as how large cracks originate from within grains of ice as small as one-twentyfifth of an inch.

The program also will provide for special access to navy personnel and expertise. A panel of national and international experts on arctic research will serve as advisors.

It was announced last summer that the world's most sophisticated ice research machine will be installed at Thayer with the help of a $213,000 grant from the Army Research Office of the U.S. Department of Defense.

The machine will be capable of testing the strength and brittleness of ice under more than 50 tons of pressure—pushing or pulling. It will be able to simulate the kind of pressure exerted by a sheet of Antarctic ice more than a mile thick, or by massive ice sheets smashing against drilling rigs or ships off the Alaskan coast.

What makes the machine so special is that it can exert this enormous pressure in three directions at the same time, each direction independent of the other. It is also capable of exerting pressure very fast: the machine's pistons can move up to six inches a second while exerting 40 tons of pressure.

The ice research machine at Thayer will be the first of its kind in the U.S. The only other ice testing facility in the world known to be able to apply pressure independently in three directions is a much smaller, less powerful unit in Hamburg, West Germany.

"The acquisition of this multiaxial loading facility constitutes a major step forward in the ice testing capability in this country and firmly establishes the Thayer School's Ice Research Laboratory as a truly unique, world-class facility," said Schulson.

Why so much interest in a remote region noted for frigid conditions and perennial ice cap? Ten percent of the earth is encrusted with ice. The arctic region potentially has the world's largest reserves of petroleum as well as enormous reserves of other min-erals, and the Arctic Ocean has a major impact on the world's climate. Defense interests in the region rely in part on improved submarine reconnaissance—how much pressure a submarine needs to exert to break ice cover under varying conditions or how it can identify the sounds of ice cracking up. The new ice research machine will be valuable in determining how much pressure is needed to break up sheets of ice or how much weight the ice sheets can support—knowledge that will have great application in the design of drilling rigs and ships passing through the Arctic.

Thayer's Ice Research Laboratory was established nearly three years ago with a grant from the Department of Defense and through a consortium of private companies and federal agencies.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureBONFIRE!

October 1986 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeaturePapa's Son

October 1986 By Everett Wood '38 -

Feature

FeatureA China Perspective

October 1986 By President David T. McLaughlin '54 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

October 1986 By C. E. Widmayer -

Article

ArticleCarl Thum: Teacher of how to learn

October 1986 By Georgia Croft -

Sports

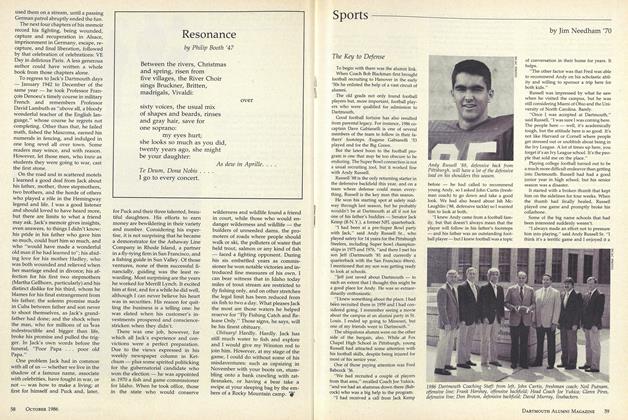

SportsThe Key to Defense

October 1986 By Jim Neeciham '70

Article

-

Article

ArticleCAMPUS NOTES

April 1919 -

Article

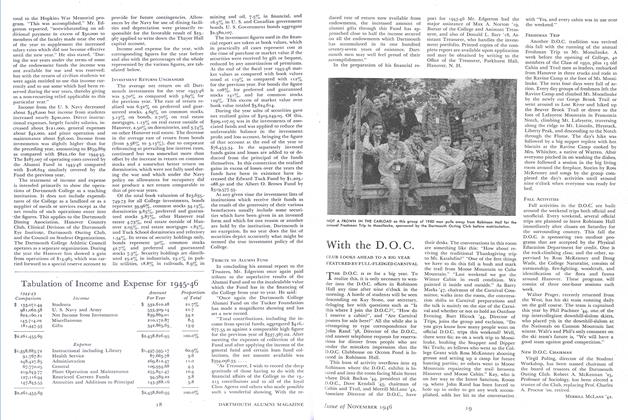

ArticleAnnual Financial Report

November 1946 -

Article

ArticleFaculty Articles

March 1962 -

Article

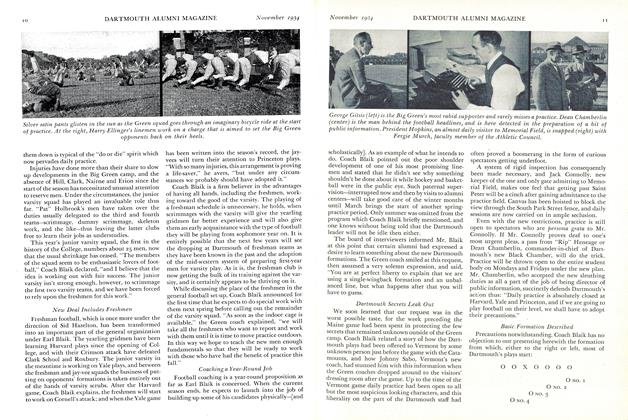

ArticleBasic Formation Described

November 1934 By C. E. W. '30 -

Article

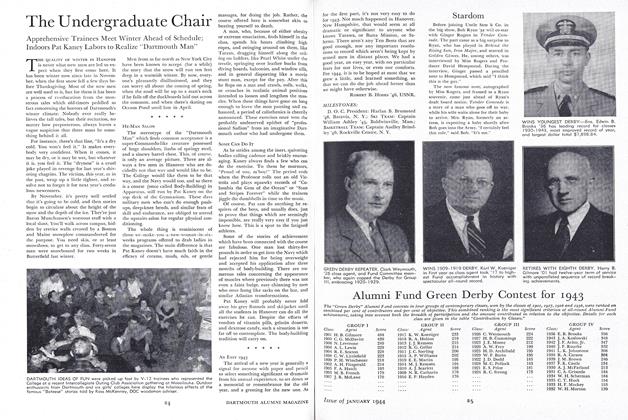

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

January 1944 By Robert B. Hodes '46, USNR -

Article

ArticleWith the Outing Club

March 1931 By William B. Rotch ’37