Random memories of Jack Hemingway '45and comments on his published memoir, Misadventures of a Fly Fisherman

My first glimpse of Jack Hemingway was prophetic; he was casting a tapered line on the lawn in Ihnestrasse, West Berlin, Germany. Watching the exhibition were Puck, his strikingly beautiful, darkhaired wife, and Joan, their fivemonth-old daughter, known then, and since, as Muffet.

The introductions over, we talked the whole afternoon. The conversation revolved around trout, Jack's work as liaison officer and interpreter with the U.S. Berlin Command, and his disgust with a certain critic who had gleefully announced that the author of the recently published Across the River andInto the Trees-Jack's father-had obviously lost his grip. I had read the same review myself and agreed the critic had no soul, didn't know what he was talking about, and should be shot. Dinner followed, deliciously prepared by Puck with Muffet in tow. Meanwhile little Muffet showed what she was made of; she bumped her head hard three times and never cried once. She just smiled.

The next year I fished a lovely stream in the Black Forest with Jack, giving me a chance to see his artistry with a rod. It wasn't fishing, however, that I most remember about our days in South Germany. It was Jack's extraordinary performance as an interpreter for an American and a French general in Freiburg on July 14, 1951, Bastille Day. Except for their rank, the two men were from different worlds and had nothing in common. The distrust of one equalled the resentment of the other. The American's courtesy call on his French host would have failed resoundingly had it not been for Jack. Every word said in English came through with Gallic charm and subtlety; every word in French echoed solid Yankee overtones. The visit over, both generals henceforth esteemed comrades-in-arms and astonished friends-embraced. Only someone deeply in love with two countries could have brought it to pass.

Jack's Spanish isn't quite up to his French he would have to be a Spaniard if it were but it's good enough. I can vouch for it. Thirty years after his Bastille Day tour de force he saved me in Chile, where we were fishing five hundred miles south of Santiago. It was a beautiful area, between the Andes and the Pacific, where rainbows and sea-run browns of unbelievable size can be found. What I couldn't find there was anyone who spoke English. Without Jack I would have starved. In my helplessness he became my interpreter, guide, gillie, chauffeur, supplier of tackle, morale-booster, and banker for 10 days. He even let me pose with a gigantic rainbow I couldn't possibly have caught myself. I should be ashamed of that picture today. But I'm not. Just looking at it makes me laugh.

In December 1984 it was my turn to render service. Mariel, Jack's youngest daughter, was getting married in New York. Would I, he asked (by then we were neighbors in Ketchum, Idaho), look after his house while he and Puck were away? Their place on the Big Wood River-a trout stream, of course-would be easy to look after. I knew it well already. But there was more than a house involved; there were 38 highly perishable, exotic plants to be watered on an exacting schedule, four dogs to feed, one lovebird to tuck in at night, and 80 chukar partridge in a pen by the driveway to protect from all enemies. For someone who knew nothing of plants and raising game birds the prospect was unnerving, yet I couldn't refuse. Two years later, I am proud that no plant withered during my guardianship, no weasel got into the chukars, and that I didn't read, however much I was tempted, a single page of Jack's manuscript which was scattered all over his studio. That manuscript became his published memoir last May. Next to the family, no one was happier than I to see it in print. Jack has lived a crazy, hectic, dangerous, wonderful life, and it's all here in his book.

Paradoxically, Misadventures of aFly Fisherman will appeal to nonfishermen as much, if not more, than it will to fanatic anglers of trout, steelhead, and salmon. The subtitle "My Life With and Without Papa" tells why. To most literate Americans the life and work of Ernest Hemingway remain of inexhaustible interest, and here is his eldest son speaking. However, because Jack, in his own right, is a master of the sport which has taken him all over the world, I comment first on his fishing.

The fervor hit Jack early, and it grew: as a child walking the banks of the Seine; as a boy, watching and fishing with his father in Wyoming; as a student at Storm King School, where perfecting his technique on local streams consumed almost as much time as his studies. At 18, already an incurable addict, he and three friends literally fished their way across the country, from the Big Two-Hearted River in Upper Michigan to the North Umpqua in Oregon. His description of that trip evokes for the true angler the sensation of cool water on waders, the vision of a fly floating on hackles, "the tangle of roots at the top end of a straightaway just below a sharp bend" where a 20inch cutthroat lies waiting. One must be in love, even possessed, to write with such total recall. And what to say of one episode which has no parallel in fishing literature?

One August night in 1944, U.S. Army Lt. Hemingway and three companions, on special OSS assignment, stared from the belly compartment of a B-17. They were looking for the fire signal of the maquisards they were to rendezvous with in occupied France. Having identified the signal, the plane descended as low as it dared, circled, and reduced speed until-with the fine phrase "Mille fois merde!" on their lips-the four men jumped into the night. Along with his other gear, Jack carried a fly rod (disguised as an antenna), reel, leaders, and assorted flies. And two days later he actually used them on a stream, until a passing German patrol abruptly ended the fun.

The next four chapters of his memoir record his fighting, being wounded, capture and recuperation in Alsace, imprisonment in Germany, escape, recapture, and final liberation, followed by that celebration of celebrations: VE Day in delirious Paris. A less generous author could have written a whole book from those chapters alone.

To regress to Jack's Dartmouth days -January 1942 to December of the same year-he took Professor Frangois Denoeu's timely course in military French and remembers Professor David Lambuth as "above all, a bloody wonderful teacher of the English language," whose course he regrets not completing. Other than that, he failed math, fished the Mascoma, earned his numerals in fencing, and indulged in one long revel all over town. Some readers may wince, and with reason. However, let those men, who knew as students they were going to war, cast the first stone.

On the road and in scattered motels I learned a good deal from Jack about his father, mother, three stepmothers, two brothers, and the horde of others who played a role in the Hemingway legend and life. I was a good listener and should loved to have heard more, but there are limits to what a friend may ask. Jack's memoir gives insights, even answers, to things I didn't know: his pride in his father who gave him so much, could hurt him so much, and who "would have made a wonderful old man if he had learned to"; his abiding love for his mother Hadley, who was both wounded and relieved when her marriage ended in divorce; his affection for his first two stepmothers (Martha Gellhorn, particularly) and his distinct dislike for his third, whom he blames for his final estrangement from his father; the solemn promise made in Cuba between father and son never to shoot themselves, as Jack's grandfather had done; and the shock when the man, who for millions of us Was indestructible and bigger than life, broke his promise and pulled the trigger. In Jack's own words before the funeral, "Poor Papa . . . poor old Papa."

One problem Jack had in common with all of us - whether we live in the shadow of a famous name, associate with celebrities, have fought in war, or not - was how to make a living; at first for himself and Puck and, later, for Puck arid their three talented, beautiful daughters. His efforts to earn money are bewildering in their variety and number. Considering his expertise, it is not surprising that he became a demonstrator for the Ashaway Line Company in Rhode Island, a partner in a fly-tying firm in San Francisco, and a fishing guide in Sun Valley. Of those ventures, none of them successful financially, guiding was the least rewarding. Most surprising are the years he worked for Merrill Lynch. It excited him at first, and for a while he did well, although I can never believe his heart was in securities. His reason for quitting the business is a telling one: he was elated when his customer's investments prospered and consciencestricken when they didn't.

There was one job, however, for which all Jack's experience and convictions were a perfect preparation. Due to the views expressed in his weekly newspaper column in Ketchum plus some spirited politicking for the gubernatorial candidate who won the election-he was appointed in 1970 a fish and game commissioner for Idaho. When he took office, those in the state who would conserve wilderness and wildlife found a friend in court, while those who would endanger wilderness and wildlife the builders of unneeded dams, the promoters of roads where people should walk or ski, the polluters of water that held trout, salmon or any kind of fish -faced a fighting opponent. During his six embattled years as commissioner he won notable victories and introduced fine measures of his own. I can bear witness that in Idaho today miles of trout stream are restricted to fly fishing only, and on other stretches the legal limit has been reduced from six fish to two a day. What pleases Jack the most are those waters he helped reserve for "Fly Fishing Catch and Release Only." Those signs, he says, will be his finest obituary.

Obituary! Hardly. Hardly. Jack has still much water to fish and explore and I would give my Winston rod to join him. However, at my stage of the game, I could do without some of his misdaventures: such as capsizing in November with your boots on, stumbling onto a bank crawling with rattlesnakes, or having a bear take a swipe at your sleeping bag by the embers of a Rocky Mountain camp.

Jack Hemingway at his home in Ketchum, Idaho.

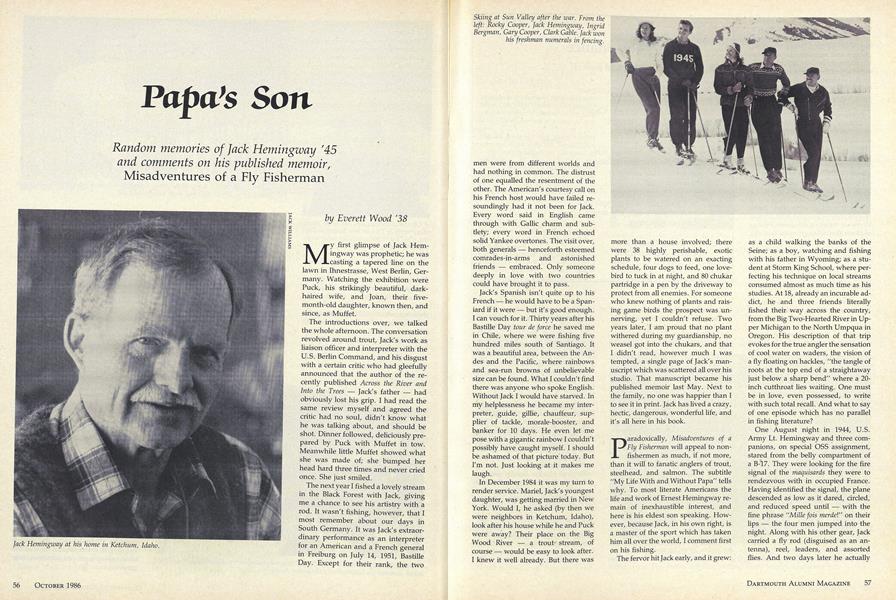

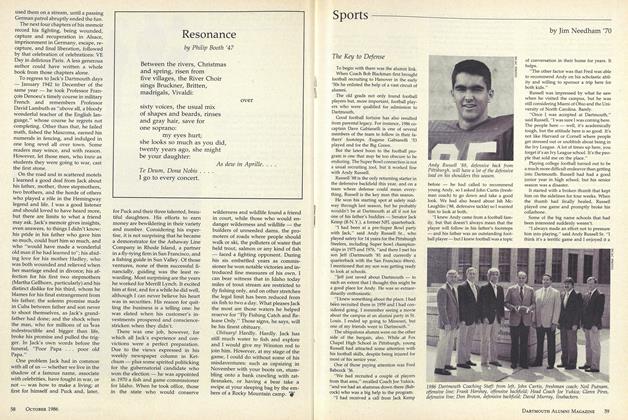

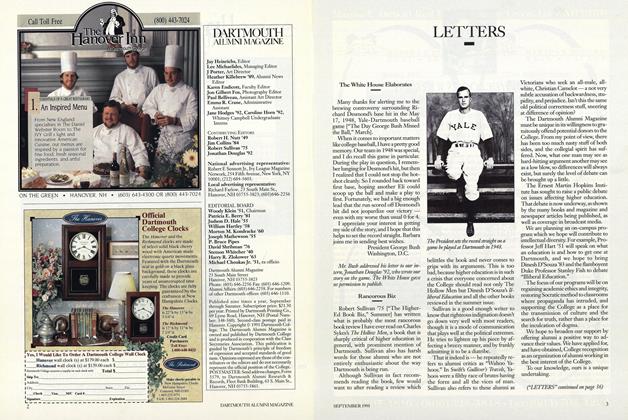

Skiing at Sun Valley after the war. From theleft: Rocky Cooper, Jack Hemingway, IngridBergman, Gary Cooper, Clark Gable. Jack wonhis freshman numerals in fencing.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureBONFIRE!

October 1986 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureA China Perspective

October 1986 By President David T. McLaughlin '54 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

October 1986 By C. E. Widmayer -

Article

ArticleCarl Thum: Teacher of how to learn

October 1986 By Georgia Croft -

Sports

SportsThe Key to Defense

October 1986 By Jim Neeciham '70 -

Article

ArticleGetting to the root of the problem

October 1986

Everett Wood '38

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS

NOVEMBER 1990 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS

SEPTEMBER 1991 -

Article

ArticleALUMNI TRY THEIR WINGS

January 1941 By Everett Wood '38 -

Feature

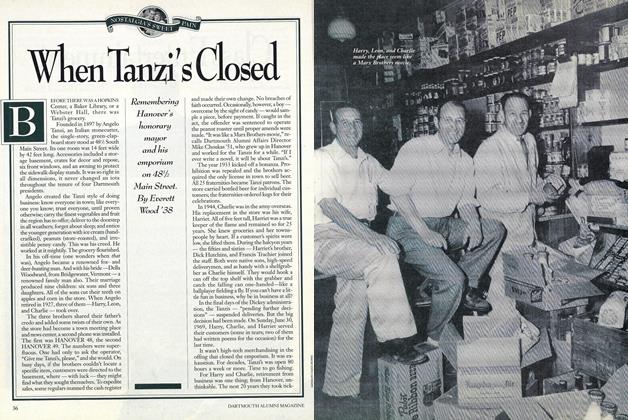

FeatureWhen Tanzi's Closed

MARCH 1991 By Everett Wood '38 -

Feature

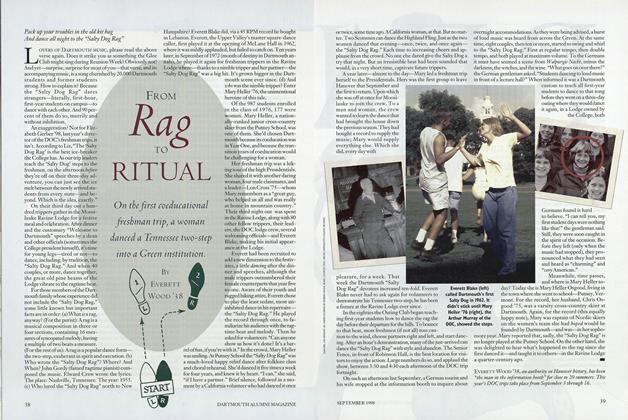

FeatureFrom Rap to Ritual

SEPTEMBER 1998 By Everett Wood '38 -

Article

ArticleThe Parkhurst Elm

OCTOBER 1998 By Everett Wood '38

Features

-

Feature

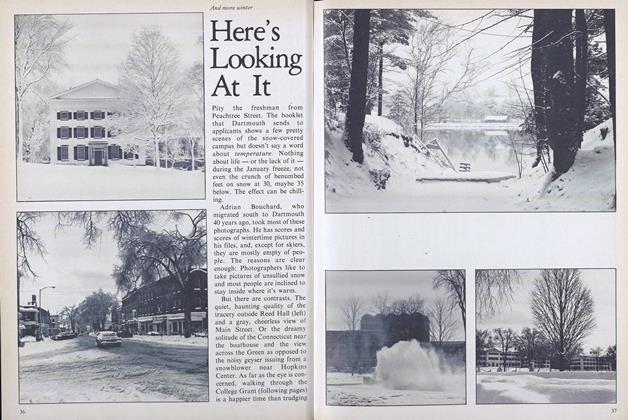

FeatureHere's Looking At It

JAN./FEB. 1978 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA New in the Neighborhood

MARCH 1984 By Debbie Schupack '84 -

Feature

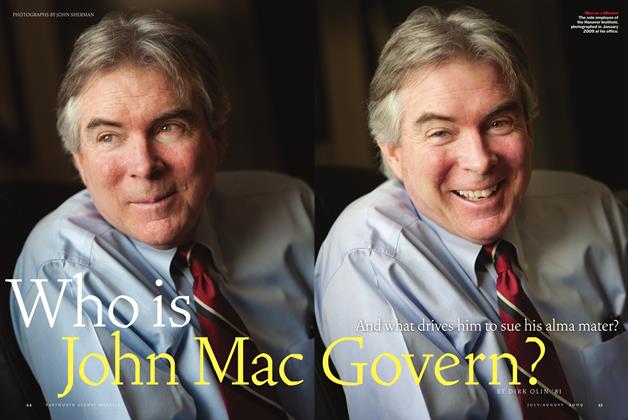

FeatureWho is John MacGovern?

July/Aug 2009 By Dirk Olin ’81 -

Features

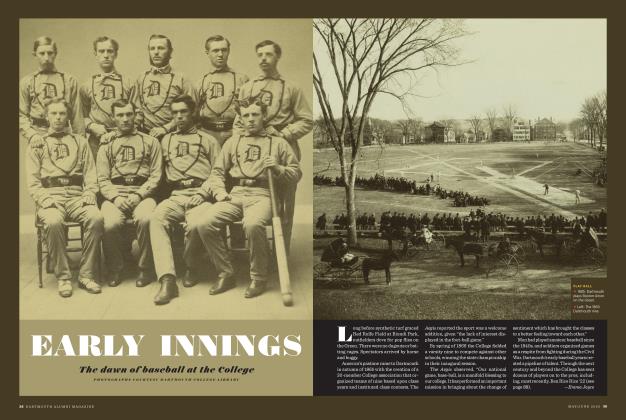

FeaturesEarly Innings

MAY | JUNE 2025 By Emma Joyce -

Feature

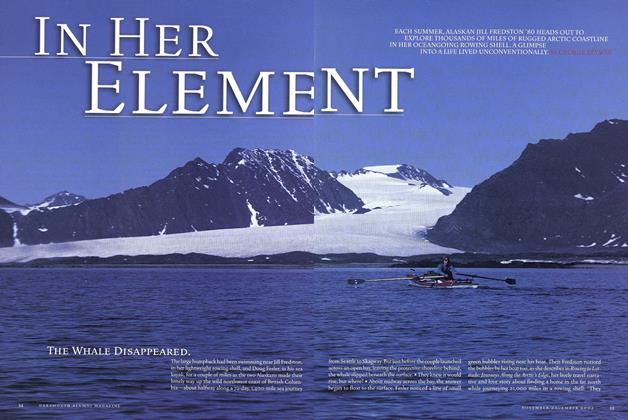

FeatureIn Her Element

Nov/Dec 2002 By GEORGE BRYSON -

Cover Story

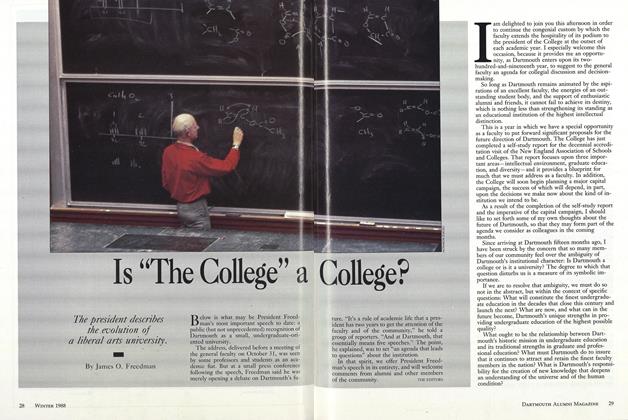

Cover StoryIs "The College" a College?

December 1988 By James O. Freedman