An illuminating look at thehistory of Dartmouth's infernos

Dartmouth Night began in 1895 as a chapel exercise designed to render the pea-green freshman fully sensible of the benefits about to be bestowed upon him. A torchlight parade and outdoor speeches were grafted onto it early in the 20th century, and somewhere along the line bonfires erupted and the athletic department got involved.

Forty to fifty alumni classes come back to Hanover on Dartmouth Night Weekend for the parade and informal reunions. Secretary of the College Michael McGean, who emcees the affair, says it has gotten bigger and fancier each year. Nowadays it bristles with flags and floats and school bands and draws a crowd of spectators 10,000 strong.

About 7:30 on Friday evening, the Dartmouth Night parade forms on the far side of Hanover and winds its flamboyant way to the Green. The Baker bells play college songs as the parade climbs the hill south of the Green and disposes itself on the steps of Dartmouth Hall. The Glee Club sings, McGean reads stirring and amusing telegrams from alumni clubs across the nation, and speakers speak. The president speaks, the students speak, and the grand marshall of the parade speaks. The coaches speak, the captains speak, and the co-captains speak. Then the Glee Club pokes everybody vertical again with "Dartmouth Undying," and the cheerleaders take over. After that, the band strikes up and leads everybody down to the Green for the climax the spectacular torching of some 800 railroad ties.

Each year a junior and a senior are hired by the college to supervise the erection of the Dartmouth Night pyre. Using pea-green labor and working to a design devised years ago by someone at the Thayer School, they oversee the laying out of a base of 12 ties arranged in a six-pointed star. The star is positioned by trial and error until the angles satisfy the supervisors. Trial and error with 180-pound railroad ties 16 feet long is apt to take a couple of hours.Then the students start stacking the ties like Lincoln logs.

As the stack rises, students climb to the top and drop lines to others on the ground, who lug over a tie, loop a line over either end of it, and yell upstairs to haul away. Two or three students climb up under each tie, letting it ride on their backs to keep it from snagging on the ties already in place. There is a bit of a scramble at the brink getting the tie up and over, but they manage, and the pyre grows, tier by tier.

When 50 star-shaped tiers are complete, a bucket loader is called in to fill the core with scrap tinder. Then more ties go up, but the pattern changes. Twenty-five tiers go up on a hexagon formed by joining the bases of the triangles that make the points of the star. The last tiers however many more it takes to equal the last two digits of the pea-greens' year of graduation are placed in a square tower that caps the hexagon. The structure is "reasonably strong," according to Kenyon Jones, associate director of athletics at Dartmouth. The pyre built for Dartmouth Night 1982 by the class of 1986 Was 86 feet high, 28 feet across at the base, and contained some 65 cords of wood.

That's a lot of wood. For years the ties used in Dartmouth's bonfires were donated by the president of the Maine Central Railroad C. E. Spencer Miller 31. The college would hire a couple of flatbed trucks, load up a bus with freshmen, and make the 130-mile trip to the Maine Central yard in Portland, Maine. The students would spend all day loading worn-out ties on the trucks, and then, dirty and tired and proud as hell, they would head back down Route 25. Jones recalls those trips wistfully. "It was a great experience. I remember once, on the way back, we passed a stand by the road where a youngster was selling lemonade. Somebody yelled 'Stop!' and 40 parched, filthy students descended on the stand. You should have seen the look on that kid's face."

But that was back in the "good old days." Eventually the Maine Central ran out of old ties, and the College had to find them elsewhere (and pay for them). "We discovered that we could hire logging trucks to do both the loading and transporting cheaper than we could hire flatbeds and transport and feed students," explained Jones. And now, apparently, railroads sell old ties only in job lots on 10-mile sections of track. On 24-hours' notice, a customer must be willing to truck away everyhing left along the right-of-way by the crew laying new ties. Only landscapers are willing to do that, it seems, and so Dartmouth now has an arrangement with a landscaping company in Burington, Vt., which sorts its ties and delivers the culls to Dartmouth. What with one thing and another, a Dartmouth bonfire now costs about $3,000.

The first bonfire appears to have been a spontaneous celebration of an athletic victory in 1888. According to the student newspaper of the day, "The convulsive joy of the underclassmen burst forth ... in the form of a huge Campus fire." It was the upperclassman's journalistic opinion that the fire "disturbed the slumbers of a peaceful town, destroyed some property, made the boys feel that they were men, and, in fact, did no one any good."

But bonfires caught on, so to speak, and in after years, athletic victories of all sorts were apt to be celebrated with fires. Before the tradition was firmly fixed and brought under the regulating hand of the administration, the townsfolk paid tribute to the victors by the loss of any number of outbuildings and other combustibles not firmly pegged down. But by 1893, the student press could look with a more favorable eye on the business of bonfires: "The bonfire celebration of the Amherst game was in several respects the most remarkable one in the history of athletic celebrations. Composed of twelve cords of pine wood liberally soaked with two barrels of kerosene, it was easily the largest and at the same time the first strictly honest bonfire that the college ever saw. It was an honest victory and appropriately celebrated with an honest bonfire; not a borrowed box, barrel, or contraband combustible of any kind was burned."

In those early years, a victory celebration began with the joyous pealing of the campus bell, followed by a prolonged period of yelling, singing, and generalized melee. Finally committees were slapped together and dispatched to fetch favorite faculty, to organize a drum corps, and to arrange for a fire. The summonsed faculty made congratulatory speeches, causing more yells and songs, and finally a parade was formed with the victorious team at its head. For a couple of hours, the students paraded about the town, stopping at professors' homes to roust out their teachers and demand speeches. At a late hour, the pyre was torched, and the students donned white nightshirts and marched in a ring about the fire. The "ghostly raiment" played on by the light of the fire was felt to be a satisfyingly "weird spectacle." A grand march, a bunched yell for each man on the team, and the singing of the Dartmouth song on the steps of Commons concluded the festivities.

When the College began to regulate the bonfires, it was the dean's office that landed the job. But in 1967, for some reason, the dean's office demurred from further incendiary efforts, and the ball was picked up by the athletic department, which has overseen the increasingly spectacular bonfires ever since. The fire itself is felt to be essential to the pre-game psychup, and the erection of the pyre has long been regarded as an important bonding exercise for the first-year class. Within recent memory, bonfires were built by the first-year students before every home football game, some three or four times a year. But about five years ago, rising costs coupled with a pea-green rebellion brought the number to two, where it has remained since. "Even if it gets to the point where they are just too damned expensive," said Jones, "we will always have one for Dartmouth Night."

It was in the early seventies, apparently, that the bonfire builders began to get carried away with height. One class, out of sheer joie de vivre, built a pyre 110 tiers high. "That was scary," recalled Jones. "It was literally swaying in the breeze. Somebody was going to get killed if that went on, so we cut them back after that, limited them to a number of tiers equal to their class numerals." (Jones did not say whether the rules will change again by the time the class of 1999 comes to town.)

It's hard to believe when you tilt your head back, back, back to look up an 86-foot tower swarming with 17- and 18-year-olds, but there have been no serious accidents connected with Dartmouth's bonfires. A number of mashed fingers, said Jones, and once a student broke her arm climbing on top of the star for fun after dark, but when the building is going on, things are, it seems, well under control, even if they look and sound like chaos.

Sponsoring mammoth bonfires isn't all a bed of roses though. Every so often there is a public outcry over air pollution, said Jones, who went on to explain that for years Dartmouth's bonfires have been vetted by both the state air pollution control board and the local fire department, neither of which regards them as significantly polluting. Other objections have been raised over the years to the wanton burning of a quantity of wood that would keep a good many New England families warm in the winter.

One year, some concerned Dartouth students organized, with the sanction of the College, a chopping and splitting project right next to the rising pyre. While some students lugged ties, others cut and split several cords of donated firewood that was later distributed to needy families in the area. The analogy doesn't work perfectly, however, because railroad ties, which are heavily treated with creosote, are unsuitable for home burning.

Once, at the height of the Vietnam War, the Dartmouth bonfire came in handy as a backdrop for a local guerrilla theater troupe acting out the plight of napalmed villagers. There have also been some amusing contretemps with the bonfires, most of them involving the scrap wood used to fill the core. (Soaked with kerosene, this wood fill assures that the pyre ignites quickly and dramatically: there's nothing worse for school spirit than a bonfire that won't catch.) Each year the Colege gets more offers of bonfire fill than it can handle collapsed sheds, rickety barns, demolished houses, whatever wood trash someone would like hauled away. Once a farmer donated an old barn, and the College sent out a crew of workers and students to tear it down. There was a mixup about directions, and it seems they tore down the wrong barn. That took a while to straighten out.

Another year someone called up and said, "I've got a church steeple in my back yard. Want it?" Jones said, "Sure," and dispatched a crane to pick it up. "It was a little bigger than we could legally transport," he recalled, "so we chainsawed it in half and brought it in in two pieces. We decided that the top half would look kind of nice perched on the top of the pyre, so we did that. Five minutes later, Dean Schaeffer came tearing out of Parkhurst shouting, 'ls that a teepee!?' I assured him that if we were going to be in trouble with anybody, it was God, not the Native Americans." Putting the steeple on top turned out to be a bum idea, though, because it blocked the draft.

This year's graduating seniors will remember vividly the Dartmouth Night bonfire of 1982. It was noon on Monday before , there were enough first-year students gathered to warrant trucking over a load of ties. By dusk, 15 or 20 tiers were up; but that night, fraternity pranksters knocked them all down. Tuesday saw the rise of some 30 tiers, over which the builders set a night watch. However while the guards were singing around a little campfire on one side of the pyre, some strong silent types from the fraternity shinnied up the other side and quietly lowered a number of ties, some of which were later found piled on the lawn in front of the president's office.

The next night, the president sent over some campus police to help mount guard. The turnout was meagre, however, through Thursday, and by midmorning of Friday, there were only 50 of the requisite 86 tiers in place. Would they make the 7:30 deadline? At 6:00 p.m., they were still struggling, but struggling at the 80-tier level. Watching them, an alumnus who was standing with his two children grinned and shook his head. "It was a lot easier in 1956," he said. By 7:30, by gum, they were done, and the 1986 banner had been tacked proudly to the 86th tier.

About 8:00, the Dartmouth Night parade circled up to the lighted steps of Dartmouth Hall. The October night rang with cheers and speeches, promises by players, and exhortations by coaches. School songs were sung, and old times recalled. Hearts were stirred and an occasional tear was shed.

Down on the Green, the nightshrouded pyre was surrounded by people from all over. Cyalume light sticks punctuated the dark like overgrown fireflies, and everywhere whisperers asked when it would go. It was a little after nine when a flame suddenly appeared near the pyre. Everybody murmured, "Ahhhhhhhh" but it was only a campfire being lighted to warm the builders.

The Dartmouth band gave a last rousing rendition, and then the torchbearers dashed forward and shoved in their brands. There was a moment of collective indrawn breath while the tiny flames scurried at the base in search of the kerosene, and then with an ominous roar, they found it, and long, thin, strawberry flames licked skyward. With a flash of red sparks, the ties themselves caught, and the whole pyre exploded in thick orange flames.

No matter how sophisticated you are, in the face of an inferno raging two hundred feet into the night sky you drop your jaw. The crowd, washed in a lurid orange glare, dropped its jaws and stared. Waves of intense heat reached the crowd and forced it back -once, twice, three times. It was magnificent and awe-inspiring, beautiful and terrifying. There was a single unnerving minute when it seemed also, somehow, blasphemous, unleashing that much fury for a lark.

Then someone, doubtless on a dare, dashed to the edge of the roaring pyre, lighted a cigarette from one of the redhot coals raining all about him, and dashed back. The moment of primal awe passed. People began to shout to each other over the roar and the crackle, speculating on how long it would take it to collapse. When it did, the crowd, sated, began to drift away, and the toppled giant burned on alone. In the small hours of the morning, the lovers and the night philosophers came to pay their respects to the dying embers.

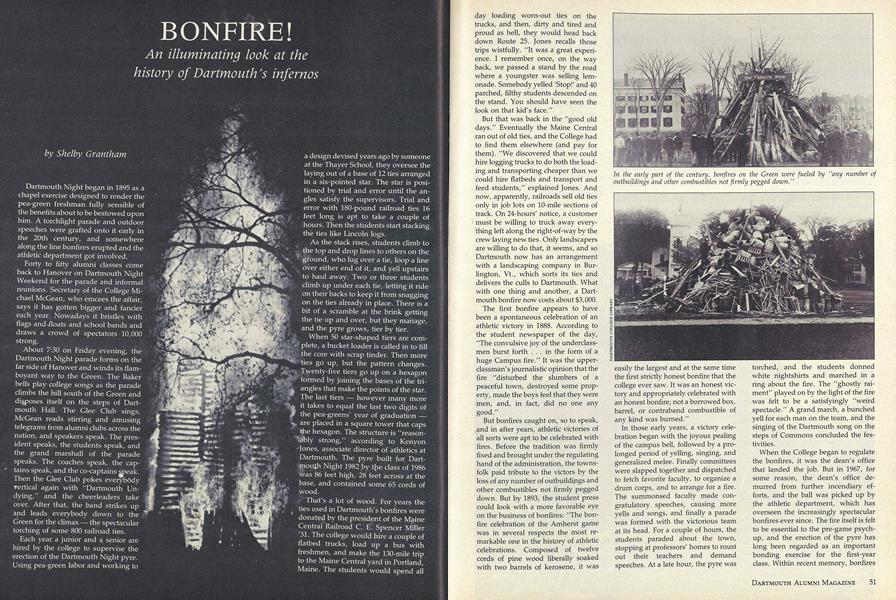

In the early part of the century, bonfires on the Green were fueled by "any number ofoutbuildings and other combustibles not firmly pegged down."

By 1949 the bonfire, though still composed ofmiscellaneous materials, had gained a bit ofheight and symmetry.

By 1960, the design of the structure and the effort of the builders, "long regarded as animportant bonding exercise for the first-year class," were carefully coordinated.

Shelby Grantham, former Dartmouth Alumni Magazine staff writer, is directorof publications for development at Dartmouth.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturePapa's Son

October 1986 By Everett Wood '38 -

Feature

FeatureA China Perspective

October 1986 By President David T. McLaughlin '54 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

October 1986 By C. E. Widmayer -

Article

ArticleCarl Thum: Teacher of how to learn

October 1986 By Georgia Croft -

Sports

SportsThe Key to Defense

October 1986 By Jim Neeciham '70 -

Article

ArticleGetting to the root of the problem

October 1986

Shelby Grantham

-

Feature

FeatureThe big eye in Arizona

SEPTEMBER 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Article

ArticleThe Children's Own Curator

MAY 1983 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureHigh Tech Crisis

JUNE 1983 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureFourth in a Pig's Eye

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureLife After the Presidency

NOVEMBER 1984 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

Feature"These Children Are the Future"

MARCH • 1987 By Shelby Grantham

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover Story"It Hasn't Been Commercialized"

Mar/Apr 2009 -

Feature

FeatureIt Was A Dartmouth Jinx All the Time

November 1960 By AMOS N. BLANDIN '18 -

Feature

FeatureHow Green Is Squaw Valley

February 1960 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

FeatureUnforgettable!

Sept/Oct 2007 By HOWARD LEAVITT ’43 -

Feature

FeatureCan Education Kill the Movies?

JANUARY 1968 By Maurice Rapf '35 -

Feature

FeatureEnd of a Golden era

APRIL 1982 By Shelby Grantham