Dartmouth's Academic Skills Center is located at the end of a long hall.

That, says director Carl Thum, is his only complaint. Thum doesn't want any barrier to come between his program and any Dartmouth students, and that long hallway might be just enough to discourage some from proceeding.

It takes a lot of courage for anyone to ask for help, Thum says, and for Dartmouth students it might be even more difficult than for others. After all, they've already proven themselves by passing all the hurdles to admission. Might someone suspect there's been a mistake if they have to ask for help now?

The idea of an Academic Skills Center at Dartmouth is an anomaly to many, primarily because it's the cream of the student crop who end up at schools like Dartmouth. But it's precisely because the students are so talented that the Academic Skills Center is necessary.

"The ability to learn is really predicated on knowing how to learn," Thum says. "These students are so bright, they've never had to know how to learn. They've just gone to class and, in a semi-passive way, absorbed information and acted on it.

"Then they come to Dartmouth, Yale, Harvard, and they get hit. Suddenly they look around themselves and say, 'l'm not as smart as I thought I was.' They start comparing board scores, and they find there are a lot higher than theirs, and that worries them. They realize there are lots of people here who can just gobble up information and retain it, while they're sitting up all night in their rooms and it's not happening."

In some cases, students' academic talents have not simply hidden a lack of learning skills but actually covered up a specific learning disability. Yes, Thum says, there are learning-disabled students at Dartmouth students who, he says, are so bright that they were able to develop such sophisticated techniques to compensate for a learning disability or dyslexia that no one -not even the student - was aware of any problem.

"Some people are going to say, 'What are they doing here? This is an institution with standards.' But these are students of at least average or above average intelligence," Thum says, "extraordinarily talented young men and women. And they have contributed greatly to Dartmouth College through their leadership and creativity."

Not all dyslexic or learning-disabled students make it that far without being confronted with enormous difficulty, of course. At Dartmouth, the confrontation usually occurs in language classes, and suddenly, someone realizes there is a problem.

"There are a good number of marginally disabled or dyslexic students here," Thum says. "Probably we have no severe dyslexics, and there are some who are moderately disabled. There are some who come here knowing that they are, but there are others who come saying, 'I don't understand this. I slaved night and day, but I didn't learn any of it.'

"It really came down upon us very quickly when we realized a handful of students had similar profiles. They were motivated, they wanted to learn, and they were trying to learn, but there was a large discrepancy between the time they were putting in and what they were getting out of it.

"Many times, these students had developed very sophisticated techniques for coping with their problems, but here, they meet their match particularly in languge studies."

It's the widely acclaimed, widely imitated language-teaching method developed by Professor John Rassias that often brings the hitherto hidden problem to the fore, Thum says. "It's very intense, very fast, and it's devastating for the dyslexic/disabled student whose language processing is slower. Most of them did well in languages in high school where they were taught in the traditional method. But language here is very intense, and it just kills them."

Brown University was the first of the major colleges and universities to formally recognize the presence of dyslexic or disabled men and women among its student body, and Dartmouth has adopted many of the programs developed by Brown to help the students adapt.

The dyslexic person has a neurological dysfunction, biological or genetic, that forces the person to develop different methods for absorbing information and converting it to knowledge. But, says Thum, "a lot of people in education don't realize that everyone learns differently. Some capitalize if they do something with the information. I learn better by being told. I don't learn as well by reading.

"That's like a dyslexic person, and that's why dyslexics are often very creative people -because they are forced to compensate. They have a neurological disability in one area, so they excel in some other area. This is particularly true of athletes. They may be miserable at math but absolutely brilliant at memorizing plays and carrying them out.

"It's a wonderful thing for Nancy and me," Thum says, referring to his colleague Nancy Pompian, "because we have become involved with a fascinating group of people."

Once a student has been identified as dyslexic or disabled, the Academic Skills Center can provide a number of services, from recommending a specialist with whom the student can work to assisting the student to develop compensatory learning techniques, to simply introducing the student to other students with similar characteristics or needs.

"Once you interview people about their experiences, you find out what they need," Pompian says. "You don't know what they need to be put in touch with until you do that interview, and once you find a particular interest, you can introduce them to another student with the same interest.

"It's a good way to get them to join a support group. You introduce them to someone else so they can see face to face there are others like them at Dartmouth. Then they begin to see that it's okay to be dyslexic at Dartmouth; there are others."

Academic assistance to college-level students comes in two forms - remedial or developmental - and Thum stresses that what his office specializes in is providing developmental assistance, whether to the dyslexic, the learning disabled, or the student who simply lacks learning skills. That's why one of the most heavily utilized services of the Academic Skills Center is the Tutor Clearing House, managed by Pompian, and why one of Thum's major concerns is getting the word out about what his office can do to help all Dartmouth students get what they can out of themsleves and their classes.

"What I've tried to do is send the word out to students that they can definitely improve their ability to learn," Thum says, pointing out that the Academic Skills Center offers classes in improving reading speed and listening skills, workshops, or counseling to help students define goals and develop systems or methods for reaching them, math anxiety workshops to help students overcome fears of mathematics and recognize academic stress, and tutoring in specific subject areas.

"This center had a low profile for a number of years until I came here in 1983, but my approach is to inundate the campus with information about what we do here, to get out the message that we can provide a personal growth opportunity for students who come to Dartmouth."

Thum found his own undergraduate learning experience exciting, but it wasn't until he'd been out of school for several years that he realized he could help others experience the same excitement.

"I graduated from Union College in 1970, and I loved learning and appreciated education," he says. "Teachers become teachers because they had good teachers, you know. I liked being in education though. I liked being in teaching-helping people learn. So I got a master's in English literature and began to get excited about helping people learn. I taught at the high-school level in a private school for a while and then went to Cornell to get a public-school teaching certificate. To pay my tuition, I started teaching at a community college, and that's when I really got hooked. Teaching adults is such a joy."

At the same time, Thum took a course from the man who has been his mentor ever since, Dr. Walter Pauk, author of How toStudy in College— "the bible," Thum says.

Thum's first course with Pauk was Teaching Reading and Thinking Skills, and it clicked. "I thought, 'Wow, this is it.' This is not taught. People teaching are not aware of the problem-solving skills inherent in their own discipline."

When a graduate assistantship opened in Pauk's office, Thum was offered the post and took it, working in Pauk's reading study center. From there he went to teach English at Olivet College in Michigan where he established the school's first learning center.

"But I had an eastern orientation, and I was interested in being in a larger institution," said Thum. "Dartmouth is a wonderful place to be. I love the outdoors, and I spend a lot of time riding, biking, canoeing, hiking, and climbing mountains. Although I didn't graduate from Dartmouth, I have that Dartmouth feeling 'in my muscles and my bones.' "

Thum also has an appreciation for Dartmouth's attempts to personalize education by keeping classes as small as possible.

"Education frequently is the mass dispersal of information in a very passive way. In a large lecture hall, as one of hundreds of students, you listen, take notes, take on large reading assignments and writing assignments. In situations like that, there is not much of a relationship between the person dispensing the information and the person taking notes.

"That's why Dartmouth prides itself on smaller classes and the opportunity for students to get to know their professors. That's one reason the alumni are so fervid, so avid about the place. It has its own institutional ethos, morality."

And within Dartmouth, Thum feels his Academic Skills Center is beginning to inspire some of the same devotion. "There are some who have made this a second home," he says. "They come daily, just to chat. Not just the undergraduates-graduate students, too.

"The beauty of working with the graduate students is that they've gotten through the personal stuff, and they don't fool around. They know they can't waste time on old methods. Graduate students write and say, 'lt made an enormous difference.' Not just a difference an enormous difference."

Thum s public relations push is paying off both in numbers and in loss of reluctance among students to seek out the services of the Academic Skills Center. While students used to hold off until their sophomore year, freshman visitors are now on the increase, and overall, some 3,000 students used the center during the 1985-1986 academic year.

"We do keep track of how people got here," Pompian says, "and now knowledge about this place is becoming standard. The students are learning about it from other students, and that means 'We trust this place.' "

About 500 students each year use the Skills Center's tutoring program which utilizes students as tutors and puts students together in pairs or groups in what Pompian refers to as "interactive learning." Part of the success of the tutoring program lies in the way tutors are selected by invitation only, Pompian says.

Thum and Pompian say they consciously seek out people who are "simpatico, who want to help other people" and who are not in it for the money, and partly because, there develops between students a rapport that can't be replicated by a faculty member or administrator working with a student.

Tutors are trained by videotape in communication skills, learning skills, and philosophy of tutoring, which is not, Thum stresses, meant to replace a professor.

"There is a temptation with a mini-class to teach," Thum says, "but our tutors are trained to get the students to talk about what is going on in the class. They facilitate learning what is going on in the class. It's just another way to help people learn."

The demand for tutors in some specific areas has become so great that study groups meeting under one tutor have been established when possible and whenever they are known to be effective, Pompian says. "Economics lends itself naturally to this kind of learning," she says. "The goal is to understand concepts of economics, and since there is not just one channel to the information, if you hear someone else's approach in a group discussion, it suddenly becomes clear. Study groups don't work in every area, but they've become standard in chemistry and organics and seem to work in mathematics and physics. We try to get professors to tell us ahead of time if their course is a good one for a study group."

Some faculty members have come to the Academic Skills Center to sharpen their own skills and improve their role as educators, Thum says, and several faculty members are participating with Thum in a new Fast Track program involving fitness, nutrition, and stress management as well as academic skills.

"The purpose," Thum explains, "is to teach students those skills and the edge that will enhance their performance potential at Dartmouth and will also serve as lifelong skills for performance potential.

"The message is that you need to be in charge of your life as much as possible to maximize your learning and performance potential.

"All of these are tools. By the time you get to Dartmouth, you've been given the plans to build a house. We give you the box of tools."

Dartmouth's Academic Skills Center, directed by Carl P. Thum, standing, offers help tostudents who havelearning disabilities, who want to increase their reading speed, or whowant to sharpen their study skills. '

Georgia Croft is editor of Echoes, a weekly community newspaper in the Upper Valley.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureBONFIRE!

October 1986 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeaturePapa's Son

October 1986 By Everett Wood '38 -

Feature

FeatureA China Perspective

October 1986 By President David T. McLaughlin '54 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

October 1986 By C. E. Widmayer -

Sports

SportsThe Key to Defense

October 1986 By Jim Neeciham '70 -

Article

ArticleGetting to the root of the problem

October 1986

Georgia Croft

-

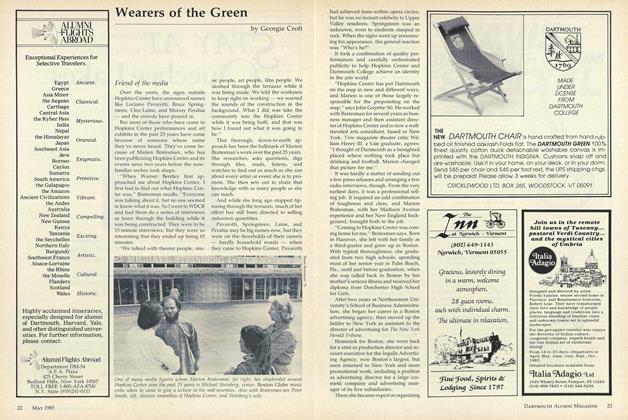

Article

ArticleFriend of the media

MAY 1985 By Georgia Croft -

Cover Story

Cover StoryBack on the Wall (where they belong)

SEPTEMBER 1985 By Georgia Croft -

Article

ArticleEfrain Guigui: Well-tempered conductor

OCTOBER 1985 By Georgia Croft -

Article

ArticleConnie Lambert: Doyenne of "The Daily D"

NOVEMBER • 1985 By Georgia Croft -

Article

ArticleMatthew Marshall: Keeper of the Inn

MARCH • 1986 By Georgia Croft -

Article

ArticleGil Fernandez '33: a fine friend to the feathered

MAY 1986 By Georgia Croft

Article

-

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE

March 1953 -

Article

ArticleAt the Boston Alumni Association

MAY 1971 -

Article

ArticleClub Calendar

November 1982 -

Article

ArticleDESCRIBE THE KIND OF FRIDAY NIGHT YOU'D LIKE TO SEE AT DARTMOUTH FIVE YEARS FROM NOW.

SEPTEMBER 1991 -

Article

ArticleHANOVER'S EARLY BIRDS

December 1961 By ALLEN R. FOLEY '20 -

Article

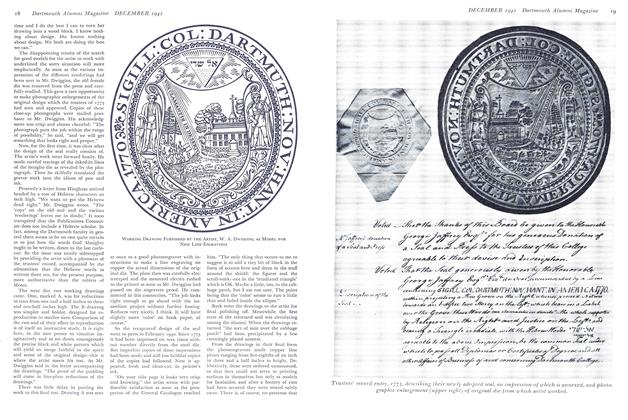

ArticleRediscovering the College Seal

December 1941 By RAY NASH