"My passion is for Africa," says Marianne Alverson. It is the first thing she chooses to say about herself.

It is hard to imagine this attractive, blond, self-described "faculty wife" in Africa, let alone the Africa she is anxious to describe: living in a remote rural village in a hut with a dung-smeared floor. It is equally hard to imagine her living in metropolitan South Africa, inviting servants to breakfast and visiting restricted Black townships.

Alverson has been the administrative assistant for the Asian Studies program since 1980. Last year she spent on leave at Princeton University with her husband Hoyt Alverson, a Dartmouth anthropology professor. She has spent much of her life following him from one academic or research appointment to another, and until recently, her own career consisted mainly of the role of helpmate and mother. But next year she will stand out on her own, as the author of a scholarly and richly personal book about Africa called Under African Sun, to be published by the University of Chicago Press as their lead offering on their spring list.

For a non-academic with a bachelor's degree and no other published works to her credit, the acceptance of this book by a major academic press is a singular personal and professional accomplishment. "I wrote it because I was obsessed by it," says Alverson. "I needed to write down the experience because I wanted to hold on to it."

Alverson can speak clearly and confidently about many aspects of her life, but just about every topic eventually gets back to Africa. Even her memories of growing up in China remind her of experiences she had while living in Africa. It is clear that in many important ways her life has come full circle, with experiences in her childhood taking on new meaning in the light of her experiences in Africa.

Until she was seven years old Alverson lived in China, the second child of parents who had left Germany prior to World War II because they were unhappy with the politics of their native country. Her family was in the import/export business, and they lived the life of expatriates, with no plans to return to Germany.

"I remember that we had servants in China, and we called them by European names. I'm sure they had Chinese names," she says, while recalling that servants in South Africa have African names, but no one bothers to learn them.

In 1947 her parents decided it was time to leave China. The forces of Mao Tse-tung were defeating Chiang Kai-shek, and even though her father was sympathetic to Mao, he did not want his children living under communist rule.

Alverson's mother was dispatched to the United States to arrange the family's immigration, since she had been born in the United States (although had only briefly lived there). They did not see her for two years. It was not easy for a German family just after World War II to immigrate to the United States, and from China. There were quotas. It took two years of negotiations. In 1949, Alverson's family got on the last boat out of China, the Woodrow Wilson, before the communists took over.

"My sister didn't understand why we were leaving," says Alverson. "My father said, 'Hear that sound?' and we could hear the guns outside the city. 'That's why we're leaving,' he said."

They landed in San Francisco and came directly to Washington, D.C. Alverson went to George Washington University and married Hoyt in 1964. Shortly afterwards, they made their first trip to southern Africa.

"My knowledge of Africa was very sparse," says Alverson. "So little is taught in our school system about Africa."

The kind of Africa one sees depends on the way one chooses to live there, according to Alverson. She has lived in two countries in Africa in two very different life-styles.

First, there is the life of the expatriate. People bring all of their culture with them and expect to live just as they did back home. And in fact, if you're white and living in South Africa, you can live better than you did back home.

"If anyone white went to South Africa," explains Alverson, "they would have a good life. A cushy life. You might have a swimming pool and a gardener. Whites have preference for jobs." .

The system of comfort, of course, depends upon apartheid an official policy of racial segregation. Blacks often live on the roofs of apartment houses in tiny cement block structures. No Whites venture up to see how the Blacks live and, according to Alverson, when she insisted on inspecting their living conditions, the white South Africans said, "Why do you want to do that?"

"Whites don't go into the Black townships. Whites aren't part of that world. They're content in not knowing. As long as they don't see it, it gives them no discomfort. They don't want you to know the Blacks. I ended up going into the townships because I had to know."

Tourists are taken on buses to see Black schools and houses. Alverson quotes the words of white South Africans, which sound uncannily like the words of slavery in the United States in 1860. But foreigners are told that South Africa cannot import American values, that South Africa is different. "They want to believe Blacks are happy," she says, "that they're better off. They try very hard to sell you the system. Our own racism prevents us from seeing it.

"Whenever I met a Black person I went through this whole explanation that I was American and not South African," she says. "I would disassociate myself from apartheid. ... We are all potentially those whites in South Africa."

She has not always been so outspoken. "No one listened to me when I came back from South Africa and Botswana. They weren't interested," says Alverson. It took several years for that to change.

In the 1960s, when her husband was speaking out at Dartmouth about the Vietnam War, she "was home in the kitchen with a baby on my hip." But then in 1984, long after she had come back from Africa, an incident occurred on campus that made a difference to her, and to many others. Looking out her window in the Asian Studies office, she noticed that the controversial sculpture "X-Delta" was being moved from its previous location in front of the Sanborn House, to a less conspicuous place between Bartlett Hall and the Sphinx. Alverson, like many people, was not a fan of the sculpture at first but had come to appreciate its value to the campus.

Before the sculpture could be moved into its new location, Alverson had staged a one woman sitdown demonstration on the proposed sight, to protest what she felt was an unfair and unilateral decision. "I didn't like the way the decision was made," says Alverson.

Hearing her tell this story, it is easier to imagine her living in Africa under very different circumstances than she had in South Africa. Not as an expatriate, but as a member of a rural Black community. In 1972 she and her husband again went to Africa on an anthropological field study. A Black South African had arranged for them to contact the woman's uncle in Botswana.

Botswana is a poor country north of South Africa, dependent upon cattle and upon exporting labor to the South African mines. Alverson and her husband and two sons moved into a small rural community and lived in a hut like most of the Black population.

"I expected they'd hate me just because I had white skin," says Alverson. "And that just wasn't the case. They're a peace-loving and generous culture. . . . South Africa is losing out. There is a lot of strength to these cultures, that they're just losing out on. The Republic of South Africa claims to want to preserve these cultures, but in fact, it is systematically destroying them."

While her husband did his field study, Alverson became very involved in the women's community of the village. Little by little she learned the language and took part in the workings of the community, including learning to smear dung on the floor of her courtyard to keep the surface hard. Her older, son went to the rural African school. The elderly uncle who had been their original contact would turn out to be a mentor to them all.

Alverson increasingly became assimilated into the village. For one year, without the luxuries of the "expatriate" life, she became more and more a natural part of the daily life of the village.

In her book, Alverson writes about her experiences in the Twsana village. It is humorous, touching, and scholarly all at the same time. She describes her first unsettling welcome by the women of the village:

She darted straight toward me, shaking her open hands back and forth. Her fingers fluttered widly, her pink tongue rolled furiously, ululating a piercing trill. She charged aggressively into my space. A breath away, her shrieking tongue and flapping hands blurred my vision and deafened my ears. I stood there, stupefied, as she circled me again and again like a vulture. I froze in terror until, to my great relief, she retreated to her group. The dance wound down. The clapping chorus faded. . . .

The next morning, she the vulture returned.... She had seemed to tower over me the day before, but now I noticed that she was actually a small woman, so slender and so old that bones protruded from her joints and deep-set wrinkles framed her eyes. . . . She approached me with a red hen in her arms, and just as she passed it on into mine, Rre Segatlhe stood by me, explaining, ke mpho [It is a gift].

After finishing the manuscript, with some trepidation she sent it to several publishers. Most were very excited by the book, but as she was told by one, "If this was about China, we'd take it. But no one's interested in Africa."

She despaired for several years and went on to other things. Chapters from the manuscript were used in several Dartmouth College courses, including Anthropology 1 and Anthropology 8. She also spoke about her experiences to the Dartmouth Institute, a program for senior corporate and government executives.

"I like to bring them into contact with this culture in a different way, more than a textbook could do." Her lectures have been very popular. She has returned to the Dartmouth Institute for three years. In addition, she has given lectures on the psychology of gender and the effects of cross-cultural contacts at Princeton University and Temple University, as well as to the National Organization for Women.

In the meantime supporters such as Noel Perrin, professor of English, were encouraging her to send her manuscript out again. Eventually the book was recommended to the University of Chicago Press by professors at Princeton and Yale and accepted.

Would she like to go back to Africa? "I'd like to go back to relive the contacts," she says. But according to recent inquiries, the people she knew in Botswana are now relocated to an unknown location, and an airport covers the land which was once her beloved village. Many of her white friends in South Africa have left the country.

Alverson talks about wanting to write fiction. She is currently taking a course in the English department and says she is working on another project, but she doesn't think of publishing for now.

Her mother comes to visit from Washington, D.C., where she lives, and likes to practice her Chinese with the professors in the Asian Studies Program.

Alverson talks about Africa and about feeding the birds in her backyard in Hanover. "Feed the birds!" she says with astonishment, thinking about the poverty in Botswana. "I can't imagine feeding the birds in Africa."

Marianne Alverson of the Asian studies department is the author of a book about Africa.

Lee McDavid is the acting editor of Vox, Dartmouth's weekly calendar of events.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

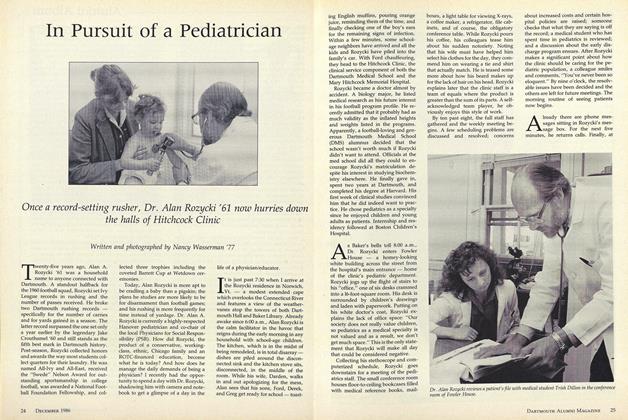

FeatureIn Pursuit of a Pediatrician

December 1986 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Feature

FeatureLawyers, Liberal Arts, and the Cold War

December 1986 By Weyman I. Lundquist '52 -

Feature

FeatureRichard Hovey: The Incomplete Arthurian

December 1986 By Daniel P. Nastali -

Feature

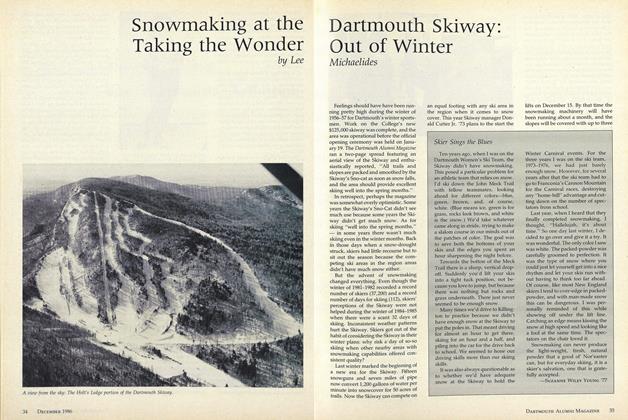

FeatureSnowmaking at the Dartmouth Skiway: Taking the Wonder Out of Winter

December 1986 By Lee Michaelides -

Article

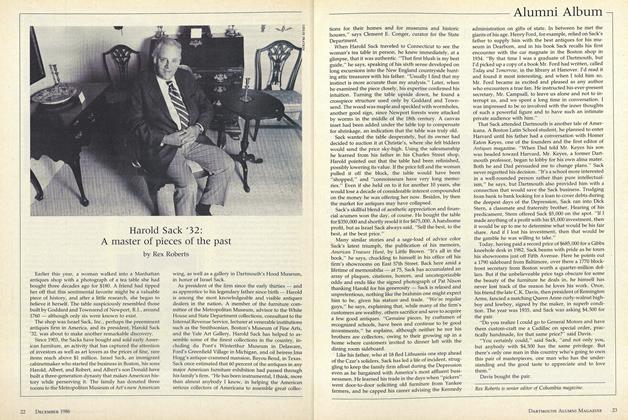

ArticleHarold Sack '32: A master of pieces of the past

December 1986 By Rex Roberts -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

December 1986 By C. E. Widmayer

Lee McDavid

Article

-

Article

ArticleMay Weekend

June 1950 By C.E.W. -

Article

ArticleCROSS COUNTRY AND SOCCER

OCTOBER 1964 By ERNIE ROBERTS -

Article

ArticleA Solution to Our Woes

JAN./FEB. 1978 By GREGORY W. AUDETTE '67 -

Article

ArticlePioneer Valley

FEBRUARY 1971 By H. J. CLARK '22 -

Article

ArticleLOVE SONG

MARCH 1963 By JOHN R. NASH '60 -

Article

ArticleTalk Back to Teacher

April 1940 By The Editor