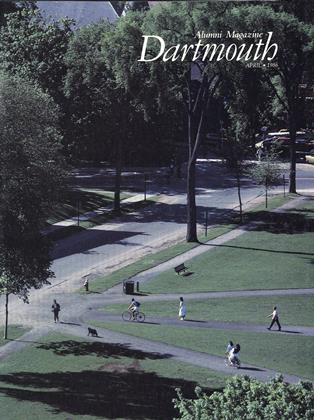

A generation ago, T.S. Eliot reminded us that "April is the cruellest month." Given the unsettling events of the last few months here at Dartmouth, let's hope his words refer only to the wasteland he envi- sioned in the early twenties — a world rav- aged by "the Great War," its fundamental assumptions shaken to the very core — and not to life in Hanover in 1986. Clearly, it is now time to assimilate what we can from this winter of our discontent, time to get on with the affairs of the College.

For the faculty, this means getting back in the classroom and exploring those ques- tions central not only to their individual disciplines, but central also to the direction education is going as we approach the year 2000. What "worked" for those who at- tended Dartmouth in those simpler times of Presidents Hopkins and Dickey needs to be reexamined in terms of the demands of to- day's complex world. For the administra- tion, it means working closely with faculty and Trustees to determine what we can do to help a small liberal arts college not just survive, but prevail. It means evaluating current resources and deciding where to build and what to phase out. For the alumni, it means becoming more involved in the general welfare of the College — not only in offering financial support, as critical as this is to the College's survival, but also by becoming more well-informed about the College and the issues facing higher educa- tion.

Why? Because the radical transforma- tion now taking place in higher edu- cation is going to create a new order in academe. Today at Dartmouth, for exam- ple, classes in everything from anthropol- ogy to music are plugged in to computers for word-processing, data storage and re- trieval, and all sorts of number-crunching. Those institutions that respond to the chal- lenge of the new technologies will attract the best students and the best faculty — and they will be molding the minds of those who will run the giant corporations and the government and set the priorities for the next generation. When John Kem- eny co-invented the computer language BASIC back in the sixties, he may well have surmised the phenomenal impact computers would come to have one day; but most of us had no idea that the silicon chip would affect our lives so momentously. Similar trends will emerge in the years ahead.

In other areas of the sciences for exam- ple, molecular biology and genetics loom so large on the horizon that schools lacking such programs in the next decade may well find themselves teaching what amounts to a course in the history of science. (A wor- thy adjunct of a graduate program at Har- vard, but not likely to lead to any new technological breakthroughs and certainly not much help to undergraduates seeking careers in medicine, biology, or chemistry.) The full implementation of such innovative programs is frightfully expensive, and iron- ically, many of them have incredibly short half-lives. But Dartmouth cannot maintain its academic foothold without them.

What gives an old English major some measure of comfort is that in spite of the impact of the sciences on the curricu- lum, the liberal arts are alive and well in Hanover — and will be 50 years hence — because no matter how good the equip- ment at your fingertips, no matter how fast it throws green-tinted images upon a video display in front of your eyes and prints them out — there's no escaping the hard work of reading, reflecting, and writing which has always been at the heart of a Dartmouth education. We will do what we can to help keep you abreast of significant changes as your College makes its way into the third millennium. But you can do even more yourself. Next time you come to Han- over, sit in on a class; talk to a few stu- dents to find out what's on their minds and how the College has changed since you took notes in 105 Dartmouth. Better yet, come back to school as a student. One self- admitted masochist who signed up for one of John Rassias's language courses over the summer commented in the current issue of Inc. magazine, "Most interesting vacation I've ever had . . . After it was over, we went down to Boston to spend the night. I slept for 14 hours straight." And not from boredom, either.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Peace Corps at 25

April 1986 By Laura T. Hammel -

Feature

FeatureSTRATS

April 1986 By Willem Lange -

Feature

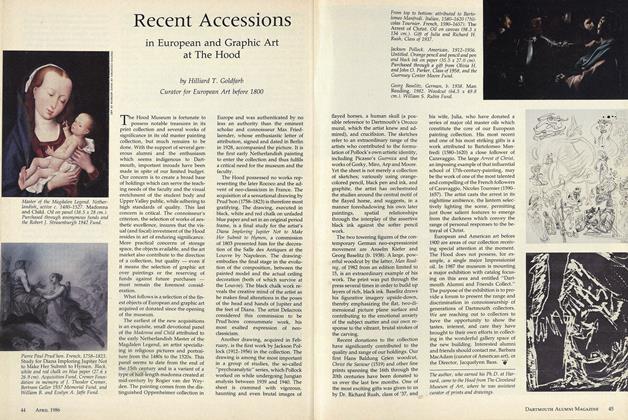

FeatureRecent Accessions in European and Graphic Art at The Hood

April 1986 By Hilliard T. Goldfarb -

Article

Article"Kiki" McCanna: Steward of Sanborn

April 1986 By Lee McDavid -

Article

ArticleRave Reviews?

April 1986 By Dorothy L. Foley '86 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

April 1986 By Richard A. Masterson

Douglas Greenwood

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor75 and Counting

OCTOBER, 1908 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorThe Fall of '63

November 1983 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorPassages

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1984 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorRuffly Speaking

NOVEMBER 1984 By Douglas Greenwood -

Article

ArticleVox Clamantis

DECEMBER • 1985 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorA Family Affair

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1986 By Douglas Greenwood