Robert Kaiser '39: Economic expertise is his planned gift to Dartmouth

APRIL • 1987 Deborah HodgesExpertise in a given subject is valuable; the skill and willingness to share that expertise is doubly so. Robert L. Kaiser '39, senior advisor in Dartmouth's Bequests and Trusts Program, has made a career of mentoring those in the field of planned giving to educational and charitable institutions. His accomplishments were formally recognized in February of this year by District One of the Council for Advancement and Support of Education (CASE), a national organization of development officers, which named Kaiser the recipient of its 1986 Eleanor Collier Award for contributions to his institution and to the profession. The awards committee went on to note that Kaiser's "willingness to share his expertise and methods ... is legendary."

His involvement in development activities began in 1965, when he came to Dartmouth as associate director of the Bequests and Estate Planning Program. For the next eight years he administered the program without assistance. In 1973 Frank Logan '52 joined the staff as associate secretary of Bequests and Estate Planning, and from 1979 to 1984 the two men acted as co-directors. In 1984, Kaiser elected to become a full-time senior advisor, shifting from an administrative role to an advisory one.

He was lured to Dartmouth in 1965 by the presence of his brother-in-law, Frank Hutchins '22 (now deceased), a friend of Ort Hicks '21, who was then vice president for development and alumni affairs at the College. And, of course, it was familiar territory from his undergraduate days as well. Kaiser graduated Phi Beta Kappa with a major in economics. In addition, he was one of eight senior fellows, with a thesis topic that was characteristically ambitious - "The Rigidity of the Price Structure." "Prices in the U.S. don't always behave as Adam Smith wanted," he said with a grin. "They often don't respond to the law of supply and demand because of government regulation, price fixing, things like that."

After graduation, Kaiser put his interest in economics to good use by joining the N.W. Ayer Advertising Agency, one of the first organizations to conduct on-campus interviews. Two years later Kaiser enlisted in the Army, where he attended field artillery Officer Candidate School and served with Patton's Third Army as a gunnery expert. He was discharged in 1945 (with two bronze stars) but continued to serve in the active reserve until 1962, retiring as a lieutenant colonel. After World War II Kaiser became chief executive officer of three industrial subsidiaries of Magnus Chemical Company in New Jersey. They were bought out in 1964, which occasioned his move to Dartmouth.

"Bequests and Trusts" was a new business at the time, new for Kaiser and for most educational institutions as well. His job at Dartmouth was to raise capital funds for the College while adhering to what has become the primary tenet of what is now known as "planned giving": maximizing support for the institution in ways that also benefit the donor. This is often accomplished through life-income giving, "something which was just getting started when I came back to Dartmouth," Kaiser said. "Instead of an outright gift," he explained, "the donor makes a gift of the principal but retains use of the income from that gift until the death of the named beneficiary." Since the recipient organization has management of the gift principal, the organization can often increase both the capital growth and the yield through prudent and professional investment strategies, thus benefitting the donor as well as the recipient.

"Bob Kaiser can rightfully be called the dean of planned giving officers in New England,' says his colleague, Frank Logan.

"He has been a highly respected technician and innovator in the specialized field of planned giving [and] an astute generalist in the wider spectrum of fund-raising. He developed almost single-handedly a program that became a model in the field. More importantly, through his good works the College's financial well-being in all of its parts has been significantly strengthened, both now and in the future."

As Kaiser developed this expertise in fund-raising, he began to share it with other institutions, consulting informally with colleagues at Yale, MIT, Exeter, Lehigh, and UVM, among others. "I even helped Harvard get started in planned giving," he says in a voice tinged with pride and amusement. "I persuaded Harvard that a life income gift was preferable to a bequest by will for both the institution and the donor. And it is. Donors get a life income and a tax deduction, and they avoid the capital gains tax. The institution gets an irrevocable gift that can often be increased in value."

Indeed, it could be argued that the U.S. tax laws are what have made "bequests and trusts" fund-raising a true profession. The most far-reaching of these laws was the Tax Reform Act of 1969, for this provided the structure under which all charitable giving operates today. The law originated in the House of Representatives as an attempt to curtail abuses by a few small foundations. Unfortunately, the early version of that law was so "misguided," according to Kaiser, "that it would have killed private philanthropy as we know it." In response, eight or ten college and university development officers formed a group that worked closely with the Senate Finance Committee and Congress' Joint Committee for Taxation to shape the charitable giving provisions of the new law. Logan praised these efforts, asserting that they brought "practicality and common sense out of potential chaos." One of the group members was Bob Kaiser.

"I was all alone in the office at the time, but I traveled to Washington almost every week for several months to work on this. It was a large effort. And it was an important one. Our small committee essentially wrote the charitable giving provisions of the new law."

Like most of our tax laws, TRA 1969 was extremely complex, and Kaiser's familiarity with its provisions soon had him on the road again as a consultant. In 1972 he helped to organize and participated in a series of American Alumni Council workshops to acquaint development officers all over the country with the new provisions, and this led, in turn, to the development of appropriate teaching materials, which were compiled into a large volume entitled Guideto the Administration of Charitable RemainderTrusts. The Guide has been updated twice, with the second edition appearing in 1975 and the third in 1978; Kaiser was coauthor of all three editions.

Long considered the tax expert at Dartmouth, Kaiser is often called upon by alumni, colleagues, and faculty members for advice (which prompts Cary Clark '62, College Counsel, to joke that Kaiser is guilty of "practicing law without a license"). Since his knowledge of tax law has been extended to include the recently enacted Tax Reform Act of 1986, it is unlikely that his guilt will diminish in the near future. "I have a liking for the technicalities of tax law," he admits, "and I seem to have a knack for it as well." Perhaps even more important is his willingness to share that expertise with others.

Students at Dartmouth know Kaiser best as advisor to the local Psi Upsilon chapter, a post he has held since 1965. Kaiser's affiliation with the fraternity goes back to his own undergraduate days, when he served as treasurer and president of the chapter. In 1975, the graduating delegation expressed its gratitude to Kaiser with the presentation of a plaque for "ten years of awesome advising"; a decade later, the class of 1985 presented a similar plaque and elected his wife, Evelyn, as a member of the chapter, making her the only female "brother."

Kaiser's presence as an advisor provides not only a sense of continuity for the fraternity but also a sense of history, for he can speak with authority of the "old days" when the College acted in loco parentis and student activities were chaperoned. "Kids today are amazed when I tell them about parietal rules," he chuckles.

But he turns reflective as he looks back on the changes he has witnessed in the fraternity system. "Until the mid-sixties," he notes, "fraternities were pretty stable, traditional institutions. After that there was a kind of a national flaunting of authority, and at Dartmouth there was coeducation as well. Fraternities became less and less responsible with the advent of coeducation." The Greek system, he believes, is essentially conservative, mirroring changes in social mores but not instigating them. "There is a tendency for fraternities to cling to traditions. The worst behavior of the seventies resulted, at least in part, from dropping traditions such as the Indian symbol. Then of course, the 1978 faculty vote to abolish fraternities at Dartmouth prompted the Trustees to 'put them on trial.' And rightfully so. Things are much better now."

Kaiser smiles when asked about his plan to retire in June. "Well, I'll retire from fulltime work," he says. "I still have a tremendous interest in development, and I'd like to stay on part-time. I feel I can still be of important help to the College. Besides, I wouldn't know what to do with myself if I retired completely."

This last statement is a little disingenuous, since his outside interests are numerous and varied. In addition to his work with the local Psi U chapter, for example, Kaiser is a member of the executive council of the international Psi Upsilon fraternity. He has been a director and is now president of its educational foundation. His labors on behalf of Psi Upsilon were recognized at the 1983 national convention with a special award for "outstanding service to the Zeta chapter . . ., the Alumni Association of the Zeta Chapter and the International Fraternity."

Kaiser has maintained an abiding affection for the College and is one of the more active members of the class of 1939, serving as class bequest chairman and member of the executive committee for more than 20 years. He is also the mini-reunion chairman, and he and Evelyn have been hosting classmates since 1965. Within the class, they are referred to affectionately as "Mr. and Mrs. 1939 in Hanover."

What is noteworthy about all of Kaiser's activities is the way in which he gives unselfishly of himself. In summing up his "personal philosophy," he notes, "I like using my knowledge and expertise in helping people and organizations I'm interested in. I get a kick out of making a contribution, putting something back in." Perhaps the CASE newsletter says it best: "Among the many thoughtful and appreciative comments that the awards committee received about Kaiser, one word kept reappearing - 'mentor.' "

Deborah Hodges is an administrative assistantin Dartmouth's anthropology department.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

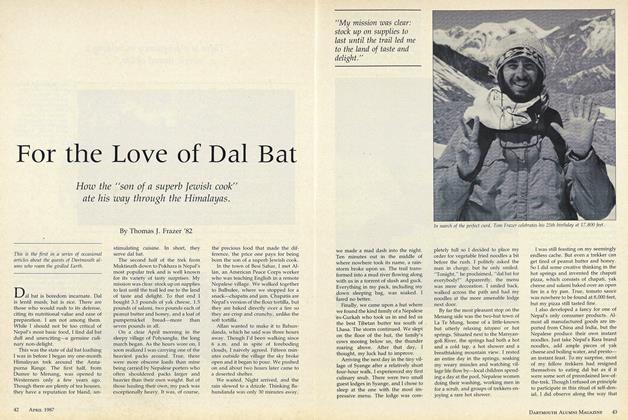

FeatureFor the Love of Dal Bat

April 1987 By Thomas J. Frazer '82 -

Cover Story

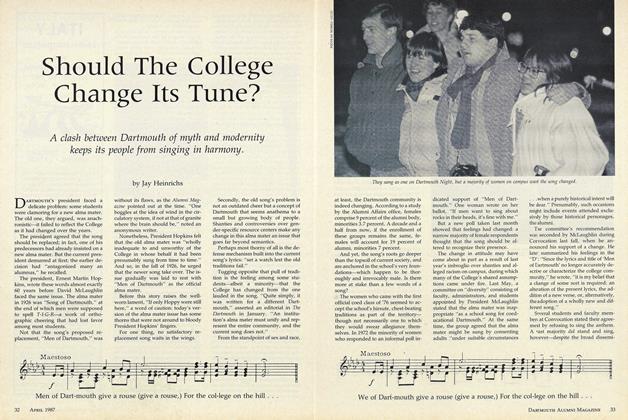

Cover StoryShould The College Change Its Tune?

April 1987 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureWish You Were Here

April 1987 By Marshall Ledger '61 -

Feature

FeatureThe Debate Over Safe Sex Lands Dartmouth on "Donahue"

April 1987 By Lee Michaelides -

Cover Story

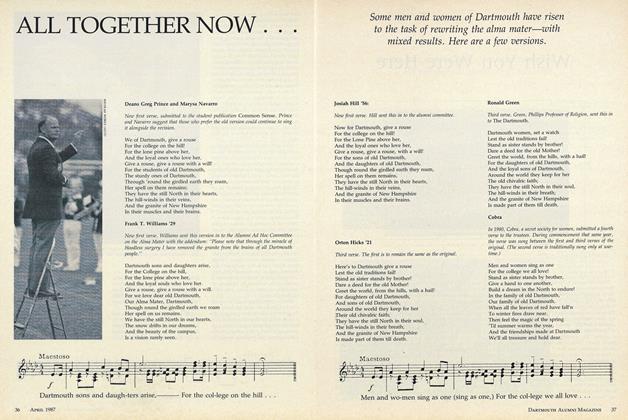

Cover StoryALL TOGETHER NOW ...

April 1987 -

Article

ArticleLeading man embraces Dartmouth; Dartmouth swoons

April 1987