How the son of a superb Jewish cook"ate his way through the Himalayas.

This is the first in a series of occasionalarticles about the quests of Dartmouth alums who roam the girdled Earth.

Dal bat is boredom incarnate. Dal is lentil mush; bat is rice. There are those who would rush to its defense, citing its nutritional value and ease of preparation. I am not among them. While I should not be too critical of Nepal's most basic food, I find dal bat dull and unexciting—a genuine culinary non-delight.

This was the state of dal bat loathing I was in before I began my one-month Himalayan trek around the Annapurna Range. The first half, from Dumre to Menang, was opened to Westerners only a few years ago. Though there are plenty of tea houses, they have a reputation for bland, unstimulating cuisine. In short, they serve dal bat.

The second half of the trek from Muktinath down to Pokhara is Nepal's most popular trek and is well known for its variety of tasty surprises. My mission was clear: stock up on supplies to last until the trail led me to the land of taste and delight. To that end I bought 3.3 pounds of yak cheese, 1.5 pounds of salami, two pounds each of peanut butter and honey, and a loaf of pumpernickel bread—more than seven pounds in all.

On a clear April morning in the sleepy village of Polysanglu, the long march began. As the hours wore on, I soon realized I was carrying one of the heaviest packs around. True, there were more obscene loads than mine being carried by Nepalese porters who often shouldered packs larger and heavier than their own weight. But of those hauling their own, my pack was exceptionally heavy. It was, of course, the precious food that made the difference, the price one pays for being born the son of a superb Jewish cook.

In the town of Besi Sahar, I met Allan, an American Peace Corps worker who was teaching English in a remote Nepalese village. We walked together to Bulbulee, where we stopped for a snack—chapatis and jam. Chapatis are Nepal's version of the flour tortilla, but they are baked directly over a fire so they are crisp and crunchy, unlike the soft tortilla.

Allan wanted to make it to Bahundanda, which he said was three hours away. Though I'd been walking since 6 a.m. and in spite of foreboding clouds, I naively agreed. Fifteen minutes outside the village the sky broke open and it began to pour. We pushed on and about two hours later came to a deserted shelter.

We waited. Night arrived, and the rain slowed to a drizzle. Thinking Bahundanda was only 30 minutes away, we made a mad dash into the night. Ten minutes out in the middle of where nowhere took its name, a rainstorm broke upon us. The trail transformed into a mud river flowing along with us in a torrent of slush and guck. Everything in my pack, including my down sleeping bag, was soaked. I fared no better.

Finally, we came upon a hut where we found the kind family of a Nepalese ex-Gurkah who took us in and fed us the best Tibetan butter tea south of Lhasa. The storm continued. We slept on the floor of the hut, the family's cows mooing below us, the thunder roaring above. After that day, I thought, my luck had to improve.

Arriving the next day in the tiny village of Syange after a relatively short four-hour walk, I experienced my first culinary snub. There were two small guest lodges in Syange, and I chose to sleep at the one with the most impressive menu. The lodge was completely pletely full so I decided to place my order for vegetable fried noodles a bit before the rush. I politely asked the man in charge, but he only smiled.

"Tonight," he proclaimed, "dal bat for everybody!" Apparently, the menu was mere decoration. I smiled back, walked across the path and had my noodles at the more amenable lodge next door.

By far the most pleasant stop on the Menang side was the two-hut town of La Te Mung, home of a little-known but utterly relaxing tatopani or hot springs. Situated next to the Marsyangoli River, the springs had both a hot and a cold tap, a hot shower and a breathtaking mountain view. I rested an entire day in the springs, soaking my weary muscles and watching village life flow by—local children spending a day at the pool, Nepalese women doing their washing, working men in for a scrub, and groups of trekkers enjoying a rare hot shower.

I was still feasting on my seemingly endless cache. But even a trekker can get tired of peanut butter and honey. So I did some creative thinking in the hot springs and invented the chapati pizza, which consists of chapati, yak cheese and salami baked over an open fire in a fry pan. True, tomato sauce was nowhere to be found at 8,000 feet, but my pizza still tasted fine.

I also developed a fancy for one of Nepal's only consumer products. Almost all manufactured goods are imported from China and India, but the Nepalese produce their own instant noodles. Just take Nepal's Rara brand noodles, add ample pieces of yak cheese and boiling water, and prestoan instant feast. To my surprise, most of my fellow trekkers had resigned themselves to eating dal bat as if it were some sort of preordained law-of-the-trek. Though I refused on principle to participate in this ritual of self-denial, I did observe along the way that all dal bats are not created equal.

Once in a blue moon you find a dal that rises above the lentil mush of its origins, reaching a relatively bearable state of edibility. Now and again the rice and dal are accompanied by boiled potatoes and an unnamed green spinachlike vegetable. But as the trail brought us to higher and less bountiful climates, the dal bats went from bad to awful.

The trek progressed upward and onward, and it became cold very fast. At last I reached Menang. At 11,650 feet, the village has the single most spectacular mountain view I have ever beheld. Rising from an arid desert plateau are the looming snowcapped monsters Annapurna III and IV, Daligeri and Gangapurna, all over 24,000 feet.

As an added bonus, Menang's Himali Lodge featured the best Tibetan bread on the trek. Every tea house made Tibetan bread, but it was usually just fried dough. The cook at the Himali actually made a brown, hearty bread, each piece about the size of a cupcake. The taste was a cross between pumpernickel and spice bread—delicious and filling.

Menang is the last substantial town before the 17,800-foot Throng La Pass which separates the Dumre/Menang side of the circuit from the Muktinath/Pokhara side. It was there at the Himali that an American doctor from the nearby Himalayan Rescue Station warned us of altitude sickness at his biweekly trekker talk. Symptoms of this affliction range from nausea to death. The doctor recommended a two-day ascent from Menang to Phedi, 15,300 feet, the last outpost before the pass, to allow the body to acclimate.

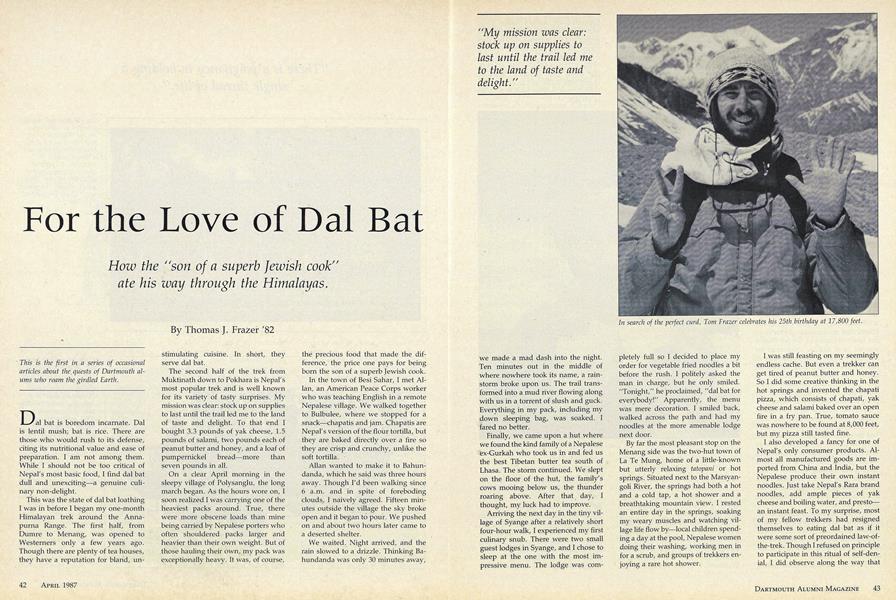

But I had my own idea. I arrived in Menang April 16 and rested the 17th. The 19th was my 25th birthday, and I had the crazy romantic idea that I had to do the pass on my birthday so as to be the highest of high for number 25. So in spite of the doctor's orders, I hiked from Menang to Phedi in one day, the 18th, spent a sleepless night in the freezing Phedi barracks, awoke at 3:30 a.m. and started hiking up the pass at 4:30 a.m.

I was not the most energetic of the group that went up that day. Most made it to the top by 9 a.m. and had a nice picnic in the sun while I was still trudging, step after slow step, in the snow and the slush.

At 10 a. m., the winds started making the cold unbearable. Every few hundred yards, I was tantalized by an unending series of false summits. Finally at 11:15, six hours and 45 minutes from Phedi, I met the Throng La. The acquaintance lasted about three minutes. The cold wind howling through the pass made picnicking unthinkable. I took a picture, had a quick look around the barren landscape and made a wild dash back down the trail

The six-hour walk down was by no means easy, but at least it was not uphill. I arrived in Muktinath exhausted at 5:30 p.m.

The first half of the trek I'd done quickly with only two rest days. By Muktinath, I was burned out and was determined to do the second half at a leisurely pace. After a two-day stop in Muktinath, I walked through the Kalagandaki—the world's widest gorge with the fiercest wind. Jomson has an airport and the Jomson Valley has electricity, the only place on the trekking circuit that does.

The 207-year-old lodge had an amazing menu that included Nepalese spring rolls. It also had an eclectic music collection ranging from Bob Dylan to Vivaldi.

Here I met Adam, a trekker from Los Angeles. He had started the trek from Dumre with his friend Dave, but Adam's knees started to cramp up after three days. The pain was too. much, so he walked back to Dumre, took a bus to Pokhara, flew to Kathmandu, flew back to Pokhara and just that morning flew to Jomson, intending to meet his friend Dave and walk down.

After resting a day in Jomson, we walked together to Marpha and discovered the delightful Baba Lodge. All of the dishes were prepared with spicy local garlic, and the place even served popcorn. To top off the meal was a surprise—fresh apple pie with creamy sweet lemon custard—a starved trekker's dream come true. The quality of life was taking a huge leap forward.

During our two days in Marpha, we witnessed a religious event. Marpha's new tolku, a Tibetan Buddhist monk who was the reincarnation of the previous tolku, came riding into town on a donkey followed by an ecstatic procession, like Jesus returning to Jerusalem. He made his way to the temple and personally blessed each of the town elders, giving each a red prayer string to tie around his neck. We were allowed to participate as special guests and were similarly blessed.

We then proceeded to Tatopani, where I enjoyed my first bath in two weeks. Best known for its natural hot springs, Tatopani featured our first taste of real improvisational gourmet cooking. The minute I saw lasagna advertised on the wall of the Namaste Lodge, I placed my order and stood in the kitchen to watch.

Into a bread pan the 11-year-old chef placed cheese imported from Pokhara, layers of homemade pasta, meat, a spicy ragout sauce and a creamy white sauce, sealing it all in with a special metal fitted cover. Around and on top of the pan he placed hot coals, allowing the concoction to bake for about 35 minutes. Off with the cover and onto a plate, it had a spectacular flavor- crunchy cheese on top, oozing cheese inside and superb spicing—pure joy.

If that wasn't enough, those Namaste masters made a bean burrito that would satisfy the most committed TexMex loyalist. Using a large chapati, Nepalese refried beans and grated yak cheese folded over and covered with chile sauce from India, they made the tastiest burrito north of the Ganges.

After that stop, the topography changed dramatically. From the snowcovered Throng La, I had hiked through the high deserts of Muktinath and the wind-shorn cliffs of the Kala Gandaki Gorge, all the way down to Tatopani at 3,900 feet. Unfortunately, I had to climb up to Ghorapani at 9,300 feet before I could continue the descent to Pokhara.

Two things made this inconvenience worthwhile. The ascent to Ghorapani goes through a bizarre rhododendron forest. The gnarled black branches silhouetted against the stark, white sky resembled grotesque human forms that seemed ready to devour us.

The other surprise lay waiting at Ghorapani's Hillside Lodge: the perfect curd. A kind of homemade yogurt, curd is available throughout India and Nepal. Hillside Lodge made its curd daily from fresh buffalo milk, and the curd settled with just the right combination of color, sweetness and aroma. The Hillside also happened to have a famed lookout, Poon Hill, only a half hour away. But by now, snowcapped mountains were becoming routine. Only food could catch my eye.

From Ghorapani, it was an easy seven-hour stroll to Birethanti at 3,400 feet, where I found six trekking friends and an impressive menu all waiting at the Dragon Lodge. By day we relaxed in the sun at the nearby swimming hole and watched the waterfalls cascade and sparkle. By night we feasted on spaghetti Nepalanese, pizza, apple pie, and chang, a millet beer. The cooks prepared an especially tasty vegetable cutlet, with potatoes, green vegetables, carrots and onions, all mashed and shaped into a vaguely steaklike form and deep fried. Dessert consisted of superb banana pancakes—creamy bananas cooked into a batter and topped with a little sugar.

Adam's mystery friend Dave finally caught up with us, having rushed from Jomson in only four days. To mark the occasion we were treated that night to a spectacular sound-and-light show of lightning, thunder and torrential rain, a vivid reminder that the spring trekking season was waning into the untrekkable summer monsoon.

After two days' walking and a onehour canoe ride, the trek was over. Though Kathmandu is usually considered the food capital of Asia, Pokhara is a close second. All of the above-mentioned delights and more were waiting for us on the Pokhara restaurant circuit. For five days the only trek I made was three times a day to the table.

And what of dal bat? Dal who?

In search of the perfect curd, Tom Frazer celebrates his 25th birthday at 17,800 feet.

Kids make the best dishes: the Himalayas' finest lasagna is concocted by an 11-year-old chef.

"My mission was clear:stock up on supplies tolast until the trail led meto the land of taste anddelight."

"Those Namaste mastersmade the tastiest burritonorth of the Ganges."

Thomas J. Frazer 'B2 left his sales job twoyears ago to backpack throughout the FarEast and Europe. He hasn't been homesince—though he plans to make it to hisfifth reunion. This article was adapted withpermission of Saturday Magazine, published by the Scottsdale Progress, Arizona.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

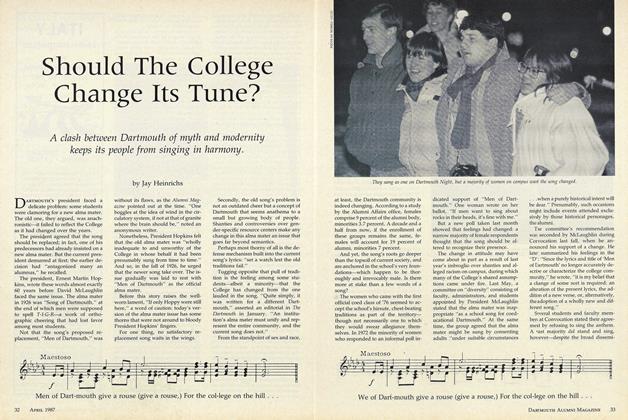

Cover StoryShould The College Change Its Tune?

April 1987 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

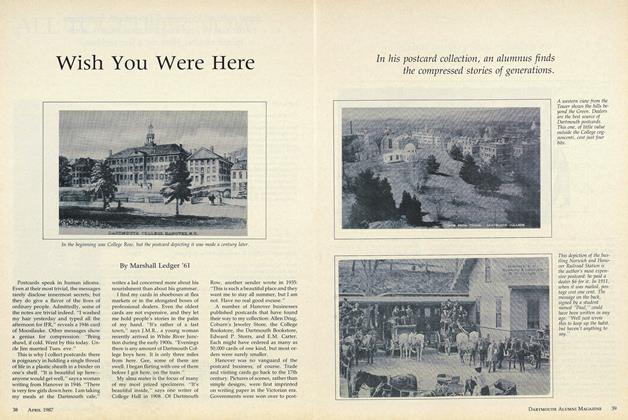

FeatureWish You Were Here

April 1987 By Marshall Ledger '61 -

Feature

FeatureThe Debate Over Safe Sex Lands Dartmouth on "Donahue"

April 1987 By Lee Michaelides -

Cover Story

Cover StoryALL TOGETHER NOW ...

April 1987 -

Article

ArticleRobert Kaiser '39: Economic expertise is his planned gift to Dartmouth

April 1987 By Deborah Hodges -

Article

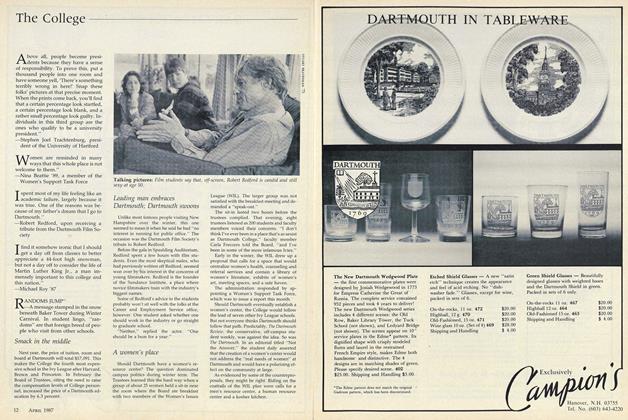

ArticleLeading man embraces Dartmouth; Dartmouth swoons

April 1987

Features

-

Feature

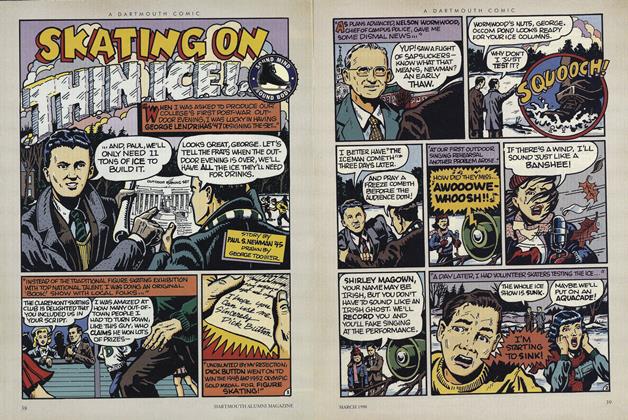

FeatureSKATING ON THIN ICE!

March 1998 -

Feature

FeatureBusiness Still Draws Its Share of Graduates

FEBRUARY 1965 By ADDISON L. WINSHIP '42 -

Cover Story

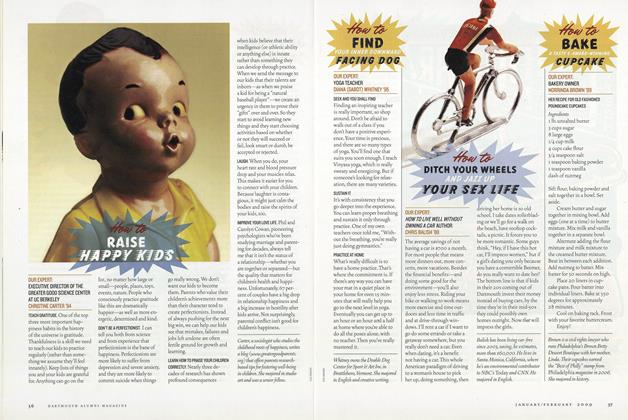

Cover StoryHOW TO DITCH YOUR WHEELS AND JAZZ UP YOUR SEX LIFE

Jan/Feb 2009 By CHRIS BALISH '88 -

Feature

FeatureThe Life of the Mind

May 1955 By DR. ALAN GREGG -

Cover Story

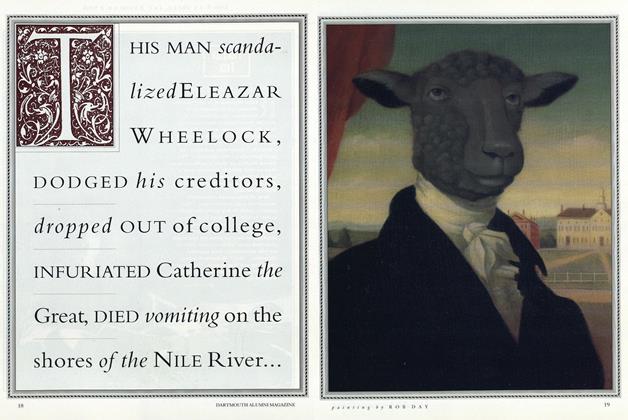

Cover StoryThis Man Scanndalized Eleazar Wheelock

June 1993 By Jerold Wikoff -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

Nov/Dec 2010 By JOHN SHERMAN