The lights go down and the film starts: flashes of kaleidoscopic color, volcanic eruptions, a faint image of a dancing woman. In 30 seconds the film is over.

This is moviemaking pushed to its limits. For three decades filmmaker Stan Brakhage '55 has shocked and delighted his viewers by painting or scratching pictures on film, superimposing or juxtaposing images, and shooting with the lens detached from the camera.

Industry cognoscenti call him King of the American Independent Film, Father of the Shaky Camera School, the Picasso of Cinema. "Brakhage is among the most astounding and innovative visionaries that film has ever produced," writes The Village Voice's J. Hoberman. David Sterritt of The Christian Science Monitor says Brakhage "strides across the cinema scene like a colossus."

His work is in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art along with that of D.W. Griffith, Charlie Chaplin and Orson Welles. Last year he received the American Film Institute's Maya Deren Award for out- standing independent film and video artists. A 300-page reference guide to Brakhage contains a 45-page list of writings about him.

Despite all the accolades, however, chances are your local multiplex does not screen Brakhage's films. Though many of his films are "staggeringly brilliant," according to Newsweek, all are "resoundingly unprofitable." Furthermore, his films don't fit into neat categories. A Brakhage documentary about Alaska does not look like "Mutual of Omaha's Wild Kingdom." Clinical is hardly the word to describe his childbirth films. His portraits, including one of Colorado Governor Richard Lamm, and treatments of the death of the family dog, sex, and his kitchen table leave some viewers offended, others merely perplexed.

A clue to Brakhage's work might be found in his early ambitions: he wanted first to become a poet. Later, he decided that versifying was not his calling. Rather than "adding another fake poet to the rostrum," he took up filmmaking, in which he could think of himself as a "poet making a film.""Film has the possibility to externalize visual thinking," he says, "to share the inner workings of the mind."

To get a private screening of the Brakhage method, close your eyes tight and rub them, and then imagine a favorite person or place. He calls this "closed-eye vision. It is not your typical feature-film cinematography which is fine with him. "The art of Hollywood is acting," he maintains. "If you use film to illustrate novels, that is the cheapest kind of filmmaking."

Although Brakhage does not make Hollywood photoplays (he uses the old-fashioned term), he has an insatiable appetite for them. From Rocky IV to Blue Velvet, Brakhage sees them all, always looking for that flash of specialness. He was so taken by the way the flashback sequence of Rocky IV was "edited with a sense of the moving visual thought process" that he saw the movie twice.

The Colorado filmmaker augments his income by teaching and lecturing. Tall and slender, with a wavy mane salt and pepper and a full beard, he looks somewhat out of place at the lectern because of the flask he carries. He chews tobacco and uses the flask as a spittoon.

In private he is a gregarious but softspoken man whose conversation tends to ramble across the artistic landscape. His lectures are like conversations, and his conversations, like short essays, are spiced with metaphoric allusions to literature, art, music and mythology ("Artists and thieves share Mercury," he reminds the listener).

Brakhage is not shy about voicing his views or risking an intellectual confrontation. Stella Pence, a director of the Telluride Film Festival, affectionately refers to him as "the festival curmudgeon." She recalls the time director Robert Wise (The Sound of Music, Star Trek) lamented the plight of the independent filmmaker. Brakhage retorted: "If you are an independent artist, what was Vincent Van Gogh?"

Brakhage came of age artistically during the Fifties, an era he feels was easier for the artist than today because the nation suffered "a hangover from the last Great Depression, and the humanities were seen as a practical benefit to society." It was against this backdrop that the young Brakhage came to Dartmouth in the fall of 1951 on an artistic (or what he calls a "Robert Frost") scholarship. Suffering a nervous breakdown, Brakhage dropped out before completing his first semester. By 1955, he was a rising star in the art world, and the College invited him back to campus for the first of many visits. In an essay he wrote for the occasion, he urged the College: "Make a place for the artist, Dartmouth, for he is the most demanding but at the same time the most generous of all individuals your tradition might speak for."

Today the Hopkins Center and the Hood Museum of Art provide artists with a home, but Brakhage discounts the value of structures unless an artistic spirit is within them. "I don't like things that set the arts apart," he says. "Arts are living, not preserving knick-knacks." To drive home his point, Brakhage refers to the residency of the late photographer/filmmaker Ralph Steiner '21: "Steiner being here was worth more than all of the buildings."

Brakhage's commitment to his muse is tempered, however,. by a sense of humor. Courted by a Hollywood company to make a feature film, Brakhage proposed a sequel to Charles Laughton's Rembrandt. He wanted to cast Buddy Hackett as the lead "to show the real condition of the artist ... do it sincere . . . but it would be funny."

If he now came into a Hollywood-sized budget, he says, he would spread the money around to small, independent filmmakers for whom the difference between completing or not completing a work is often a few thousand dollars. Brakhage knows the relationship between money and art. Financial concerns caused him literally to stop printing his films a few years ago. "I'll continue to shoot and edit films, but I can't afford to print them," he told a biographer. "There will be films I'll never see in my lifetime."

In the past year he put himself in debt to produce hours of new work a prolific amount of filmmaking. "I feel this is the time to get this work out there," he says. And if he again runs into a cash crunch? "Shoot the original and run it."

Staff Writer Lee Michaelides moonlights as the film critic for thedaily "Valley News."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryLooking for Mr. Goodjob

May 1987 By Jock McDonald '87 -

Feature

FeatureA Spanish Galleon's Real Treasure

May 1987 By R. Duncan Mathewson III '60 -

Feature

FeatureThe Uncompetitive Society

May 1987 By Richard D. Lamm -

Feature

FeatureThe Official Dartmouth Reunion Guide to Greenspeak

May 1987 -

Sports

SportsA Fast-Balling Junior Mulls Going Pro

May 1987 By Jim Needham -

Class Notes

Class Notes1983

May 1987 By Kenneth M. Johnson

Lee Michaelides

-

Article

ArticleThe "Ubiquitous" Wendy Becker

June 1987 By Lee Michaelides -

Feature

FeatureBad Things You Learned in Gym

OCTOBER • 1987 By Lee Michaelides -

Feature

FeatureThe Dean

December 1987 By Lee Michaelides -

Article

ArticleLooking Inward

December 1988 By LEE MICHAELIDES -

Article

ArticleDumpster Diver

Mar/Apr 2006 By Lee Michaelides -

Feature

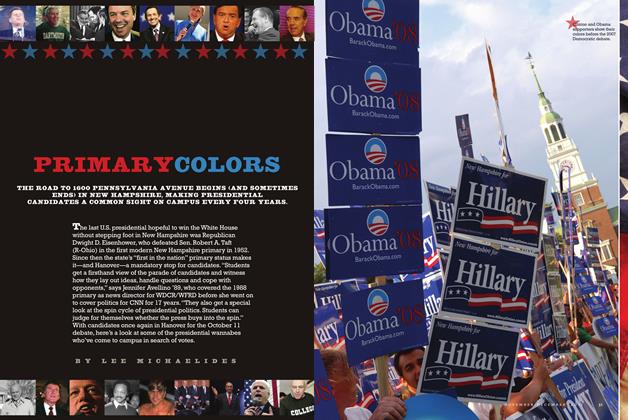

FeaturePrimary Colors

Nov/Dec 2011 By LEE MICHAELIDES

Article

-

Article

ArticleHeads Irvington House

March 1952 -

Article

ArticleStudent Researchers

January 1961 -

Article

ArticleBasketball

February 1951 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticleThe Baffling Bradley Contest

December 1976 By GALEWESCOTT -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

April 1953 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleThe Valedictories

JUNE 1977 By JOHN FINCH