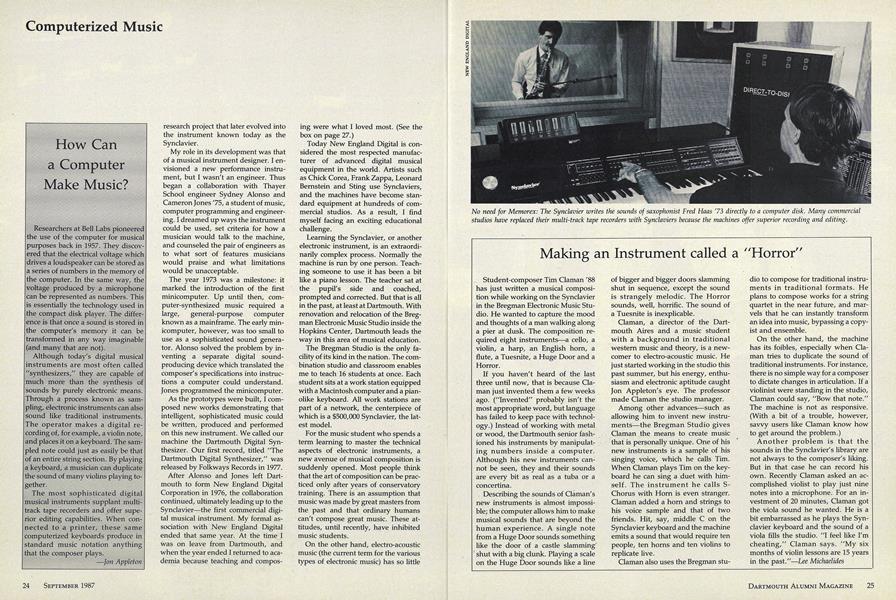

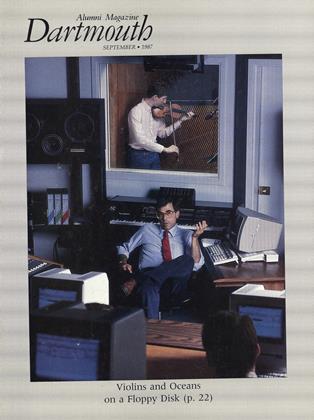

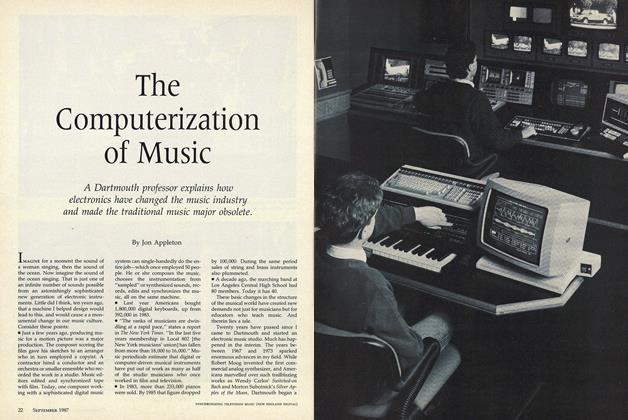

Student-composer Tim Claman 'BB has just written a musical composition while working on the Synclavier in the Bregman Electronic Music Studio. He wanted to capture the mood and thoughts of a man walking along a pier at dusk. The composition required eight instruments—a cello, a violin, a harp, an English horn, a flute, a Tuesnite, a Huge Door and a Horror.

If you haven't heard of the last three until now, that is because Claman just invented them a few weeks ago. ("Invented" probably isn't the most appropriate word, but language has failed to keep pace with technology.) Instead of working with metal or wood, the Dartmouth senior fashioned his instruments by manipulating numbers inside a computer. Although his new instruments cannot be seen, they and their sounds are every bit as real as a tuba or a concertina.

Describing the sounds of Claman's new instruments is almost impossible; the computer allows him to make musical sounds that are beyond the human experience. A single note from a Huge Door sounds something like the door of a castle slamming shut with a big clunk. Playing a scale on the Huge Door sounds like a line of bigger and bigger doors slamming shut in sequence, except the sound is strangely melodic. The Horror sounds, well, horrific. The sound of a Tuesnite is inexplicable.

Claman, a director of the Dartmouth Aires and a music student with a background in traditional western music and theory, is a newcomer to electro-acoustic music. He just started working in the studio this past summer, but his energy, enthusiasm and electronic aptitude caught Jon Appleton's eye. The professor made Claman the studio manager.

Among other advances—such as allowing him to invent new instruments —the Bregman Studio gives Claman the means to create music that is personally unique. One of his new instruments is a sample of his singing voice, which he calls Tim. When Claman plays Tim on the keyboard he can sing a duet with himself. The instrument he calls SChorus with Horn is even stranger. Claman added a horn and strings to his voice sample and that of two friends. Hit, say, middle C on the Synclavier keyboard and the machine emits a sound that would require ten people, ten horns and ten violins to replicate live.

Claman also uses the Bregman studio to compose for traditional instruments in traditional formats. He plans to compose works for a strinquartet in the near future, and marvels that he can instantly transform an idea into music, bypassing a copyist and ensemble.

On the other hand, the machine has its foibles, especially when daman tries to duplicate the sound of traditional instruments. For instance, there is no simple way for a composer to dictate changes in articulation. If a violinist were standing in the studio, Claman could say, "Bow that note." The machine is not as responsive. (With a bit of a trouble, however, savvy users like Claman know how to get around the problem.)

Another problem is that the sounds in the Synclavier's library are not always to the composer's liking. But in that case he can record his own. Recently Claman asked an accomplished violist to play just nine notes into a microphone. For an investment of 20 minutes, Claman got the viola sound he wanted. He is a bit embarrassed as he plays the Synclavier keyboard and the sound of a viola fills the studio. "I feel like I'm cheating," Claman says. "My six months of violin lessons are 15 years

in the past."—Lee Michaelides

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureMystery on the Mountain

September 1987 By Daniel Q. Haney -

Feature

FeatureDiary of a Long Distance Runner

September 1987 By Tim Hartigan '87 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Computerization of Music

September 1987 By Jon Appleton -

Feature

FeatureThe Speech

September 1987 -

Feature

FeatureHeeding the Beat of a Different Drummer

September 1987 By Teri Allbright -

Class Notes

Class Notes1976

September 1987 By Martha Hennessey

Lee Michaelides

-

Feature

FeatureThe Man Who Invented the Ant Farm (Not to Mention the Ant Coal Mine)

December 1988 By Lee Michaelides -

Article

ArticleLooking Inward

December 1988 By LEE MICHAELIDES -

Article

ArticleINTERPRETING THEATER AND TERROR

FEBRUARY 1989 By Lee Michaelides -

Feature

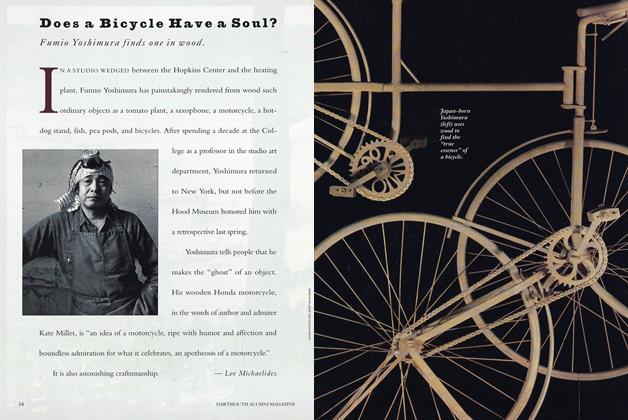

FeatureDoes a Bicycle Have a Soul?

June 1993 By Lee Michaelides -

Interview

InterviewQ & A

May/June 2007 By Lee Michaelides -

ARTIFACT

ARTIFACTSchool Spirit

May/June 2013 By Lee Michaelides