EVERY NOW AND THEN MOTHER Nature appears on the public scene. You may have caught her in that low-fat margarine commercial some years ago. Or you might see her mentioned in letters to editors about the overwhelming power of natural disasters. But this Mother is a cartoon character; time was when she was someone to reckon with.

Up until the fourteenth century, Europeans thought that nature was alive, according to Naomi Oreskes, a Dartmouth earth sciences professor who outlined nature's biography at this summer's Alumni College on "Riddles of Creation." Not only was nature once considered a living organism, she was thought of as a responsive, sensitive, life-giving female. Preserved in engravings from those times, this imagery was not just a sweet aside to more concrete conceptions of the world. It was the worldview. Even Aristotle placed the female principle at the center of the world, under God's heavenly gaze.

This idea of nature as a life-giving mother "had consequences," Oreskes maintains. "There were many things one simply did not do: One did not kill one's mother. One did not rape and pillage one's progenitor."

Miners paid this mother particular heed, says Oreskes, who happens to be a specialist in the geology of mining. Despite knowing that minerals were inorganic, people believed that they precipitated from the blood of the earth (hence the term veins of metals). If left alone, minerals would replenish naturally. Some people interpreted this as a nod to mining on a limited scale, while others condemned underground mining as tantamount to disemboweling or raping Mother Earth.

But the concept of Mother Nature slowly eroded over several centuries as Europeans faced one disaster after another. The population swells of the twelfth century had led to such widespread crop failures that by the early 1300s food shortages and mal- nutrition were commonplace. On top of this misery the Black Death wiped out 60 percent of Europe's population, some 23 million of Mother Nature's children. "It became increasingly difficult to view nature as beneficent, " notes Oreskes with professorial understatement. "It became increasingly common to view nature as something that needed to be brought under control."

Even after the plague lifted, Mother Nature came under further attack. During the age of exploration and the rise of mercantilism, increased demand for natural products loosened some of the previous constraints against exploiting the Earth. Indeed, engravings from that period portray nature as being hotly pursued by man. Then just as Europe was convulsing under the Protestant Reformation, science hammered one final nail in the coffin of old ideas. "Copernicus and Galileo challenged the notions of the incorruptibility of the heavens," Oreskes says. "On multiple levels, social, religious, economic, intellectual, the elites of Europe increasingly sought to impose order, to get nature and society under control. The result was a new worldview in which nature became suspect."

By the seventeenth century Sir Francis Bacon had elevated these suspicions to a science by subjecting nature to the experimental method, the new form of inquiry he had developed. "In Bacon's experimental method, nature was to be hounded and interrogated in a manner analogous to the interrogation of witches in his era," says Oreskes. "Bacon repeatedly referred to scientific inquiry as a form of interrogation, even torture." Mother Nature didn't stand a chance. "At best, Bacon's nature is a recalcitrant mistress who needs to be seduced. At worst she is a witch, a slave, perhaps a whore, and it is the scientist's prerogativenay, duty—to hound her, pursue her, and subdue her." And subduing nature meant killing her.

It was execution by redefinition. As scientists discovered the laws of math- ematics and motion, they recast nature as a machine. And, says Oreskes, in this "mechanical" worldview, man was free to use nature like any other machine. The scientific revolution had put nature up for unrestrained material as well as intellectual grabs.

"Certainly, there can be little doubt that each of us has been the beneficiary of this tradition of inquiry in countless ways," Oreskes admits. "In this respect it would be disingenuous in the extreme to imply that the scientific revolution was a bad thing.

"And yet, where there are gains, there are also losses. In the scientific revolution, we lost a worldview in which humans had a fundamental and intimate relation with nature."

And, in the end, that may prove the biggest loss of all.

Ever sincethe Renaissance,Mother Natureain't what sheused to be.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

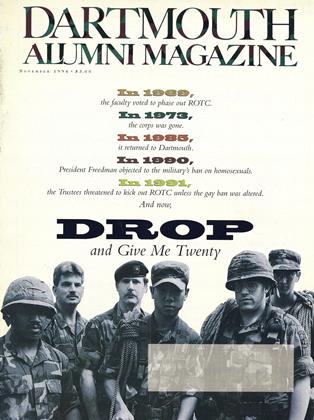

Cover StoryYou Thougnt Rotc was Dead?

November 1994 By Frederic J. Frommer -

Feature

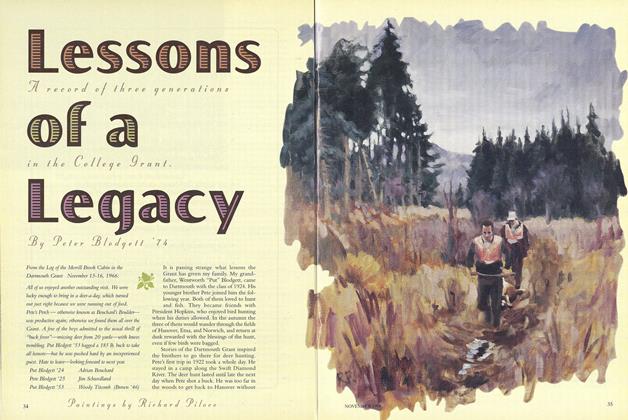

FeatureLessons of a Legacy

November 1994 By Peter Blodgett '74 -

Cover Story

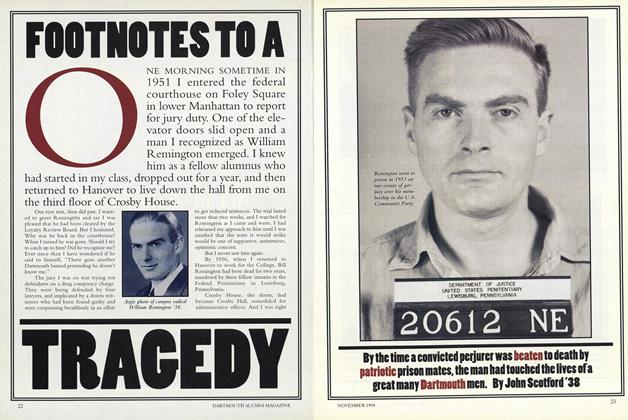

Cover StoryFOOTNOTES TO A TRAGEDY

November 1994 By John Scotford '38 -

Feature

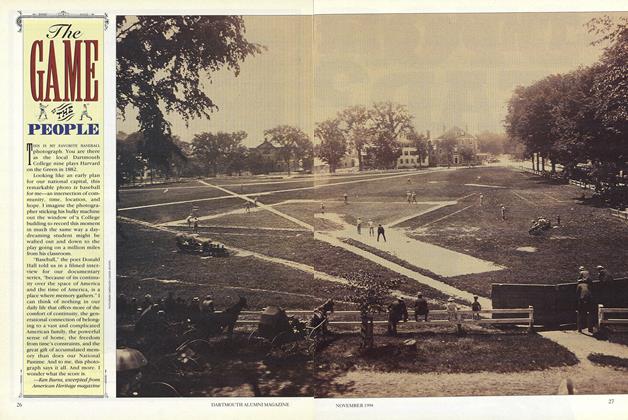

FeatureTHE GAME PEOPLE

November 1994 By Ken Burns -

Class Notes

Class Notes1980

November 1994 By Daniel Zenkel -

Article

ArticleEssayists and Solitude

November 1994 By James O. Freedman

Karen Endicott

-

Article

ArticleProfessor Sergei Kan:

September 1992 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleThe City Peter Built

Winter 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleWhy the Novel Matters

May 1994 By Karen Endicott -

Article

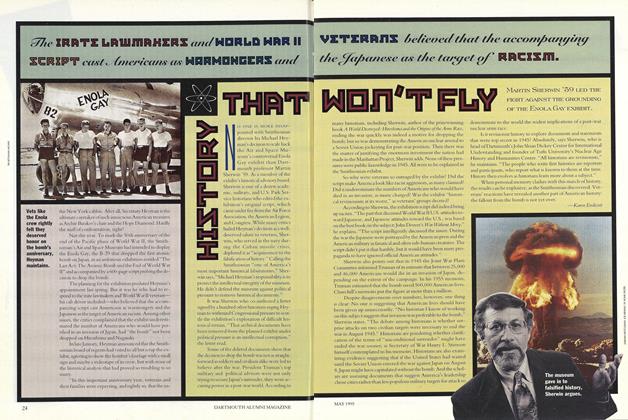

ArticleHISTORY THAT WON'T FLY

May 1995 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleMemory and Catastrophe

June 1995 By Karen Endicott -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorYou could say a woman started it all.

MARCH 1997 By Karen Endicott

Article

-

Article

ArticleFACULTY MEMBERS PROMINENT IN LONGHURST PINAFORE PRODUCTION

January, 1925 -

Article

ArticleHeads Alumni Fund

April 1939 -

Article

ArticleWith the Faculty

March 1948 -

Article

ArticleSWIMMING

March 1950 By Francis E. Merrill '26 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH CLUB OF LOWELL

June, 1926 By Samuel Abbott Lamson -

Article

ArticlePassing of Ledy Bridge

February 1939 By William T. Adams '34