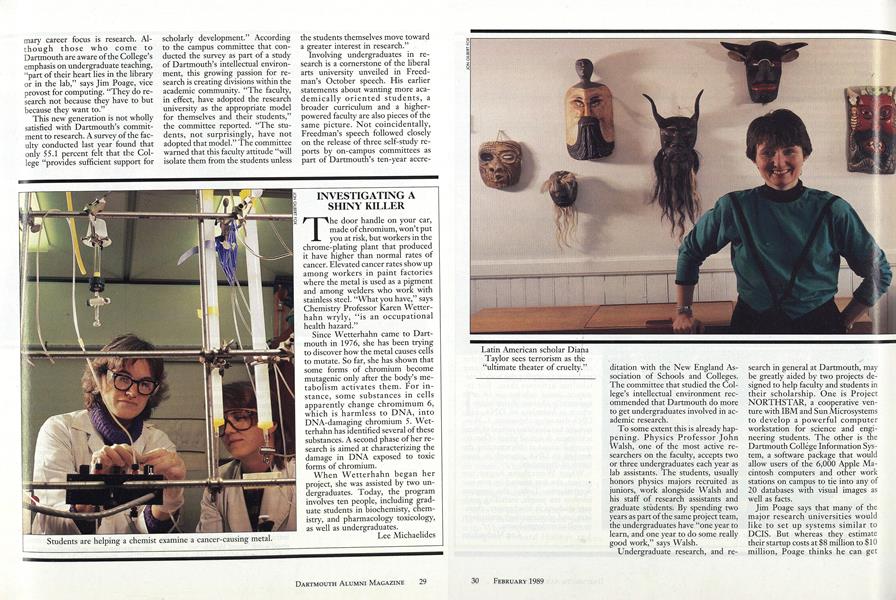

The door handle on your car, made of chromium, won't put you at risk, but workers in the chrome-plating plant that produced it have higher than normal rates of cancer. Elevated cancer rates show up among workers in paint factories where the metal is used as a pigment and among welders who work with stainless steel. "What you have," says Chemistry Professor Karen Wetter hahn wryly, " is an occupational health hazard."

Since Wetterhahn came to Dartmouth in 1976, she has been trying to discover how the metal causes cells to mutate. So far, she has shown that some forms of chromium become mutagenic only after the body's metabolism activates them. For instance, some substances in cells apparently change chromimum 6, which is harmless to DNA, into DNA-damaging chromium 5. Wetterhahn has identified several of these substances. A second phase of her research is aimed at characterizing the damage in DNA exposed to toxic forms of chromium.

When Wetterhahn began her project, she was assisted by two undergraduates. Today, the program involves ten people, including graduate students in biochemisty, chemistry, and pharmacology toxicology, as well as undergraduates.

Students are helping a chemist examine a cancer-causing metal.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Rise of Research

February 1989 By Anne Bagamery '78 -

Feature

FeatureGeorge's College

February 1989 By Constance E. Putnam -

Feature

FeatureA Story of Drama, Fierce Competition, Mom and Apple Pie

February 1989 By George Canizares -

Article

ArticleREVIEW STUDENTS ARE BACK

February 1989 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1988

February 1989 By Chuck Young -

Article

ArticleThe Battle Against AIDS

February 1989 By Martha Hennessey '76

Lee Michaelides

-

Feature

FeatureLife on Campus Is Slated for an Overhaul

June 1987 By Lee Michaelides -

Article

ArticleMaking an Instrument called a "Horror"

SEPTEMBER 1987 By Lee Michaelides -

Feature

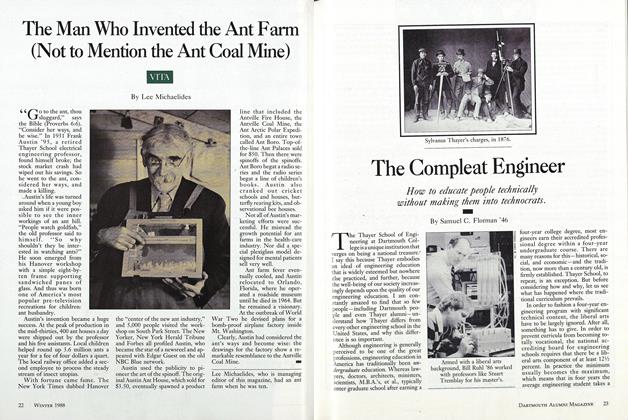

FeatureThe Man Who Invented the Ant Farm (Not to Mention the Ant Coal Mine)

December 1988 By Lee Michaelides -

Article

ArticleCourts Decide Fate of New Building

July/August 2008 By Lee Michaelides -

Article

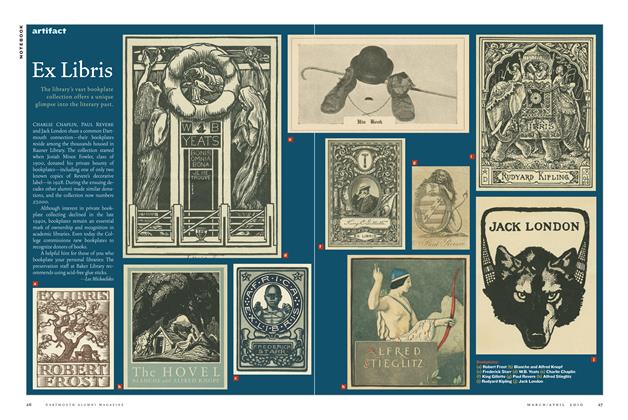

ArticleEx Libris

Mar/Apr 2010 By Lee Michaelides -

Feature

FeatureMen in Uniform

Sep - Oct By LEE MICHAELIDES

Article

-

Article

ArticleFreshman Baseball

August, 1911 -

Article

ArticleThe War and the College

October 1942 -

Article

ArticleMartin '31 Named Head Of Alumni Association

July 1955 -

Article

ArticleHouse Call

OCT. 1977 -

Article

ArticleRochester

OCTOBER 1970 By ALLAN R. KARCHER ’51, Dick Portland "58 -

Article

ArticleSquire of Tatterhummock

May 1979 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42