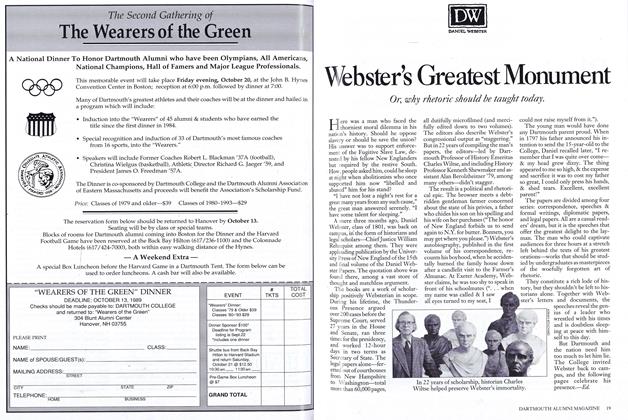

Shortly after I began practicing law in Arizone 35 years ago, I noticed hanging on the wall of the office of the United States Attorney a lithograph of someone who is obviously Daniel Webster making a speech to a group of people who looked like other Senators. I asked the U.S. Attorney what the occasion was, and he said that it depicted Webster's Reply to Hayne. I did not know much more about Webster's Reply to Hayne than the peroration, to which I had been exposed somewhere during ray education, and I think the same was true of the U.S. Attorney.

As I was preparing my remarks for today I thought back to this incident, and realized that it took place about a century and a quarter after Webster delivered that speech. Then I asked myself, "Is it conceivable that 125 years from now indeed, 25 years from now that people would have paintings on the wall of a present-day Senator or representative delivering a speech in the legislative chamber while colleagues crowded in to hear?" The answer is, obviously, "No." Ln a way, this summarizes the differences between the times of Dan .el Webster and our own times. It is easy to make too much of these differences, and to exaggerate them often to the benefit of the dead and departed. Webster, Clay and Calhoun were—none of then? consistent in the views they expressed throughout their long lives. Indeed, each of them seemed to exemplify Emerson's rriaxim that "a foolish cons istency is the hobgoblin of little minds." None of them was above reproach in keeping the political bargains he made. Webster was venal even by the standards of his own day, since he encouraged the solicitation of funds from wealthy Bostonian constituents to maintain his lavish lifes; yle in Washington. All three of the Triumvirate Webster, Clay, and Calhoun were badly bitten by the Presidential bug, and it showed in their conduct.

But when all of this debunking is given its due, there does, it seems to me, remain a difference betweenthese three giants of the first half ofthe 19th century and public figuresof more recent times. Calhoun, Clayand Webster all sat down by themselves on numerous occasions and"either wrote out a speech or at leastnotes which would be used in delivering a speech on some great issue.By the standards of our times, these speeches were often incredibly long,and reading them today, it can fairlybe said, is, in places, incredibly dull.But we must also remember that atthe time these speeches were giventhere were far fewer competing;modes of entertainment or enlightenment than there are today. In this the orators of the 19th century werefortunate; those exposed to theemotional rollercoasters of today'stalk shows would hardly be lilcely toweep at Webster's peroration in theyDartmouth College case.

These statesmen were at least willing to stand up and publicly say what they thought about an important public question, and to give the reasons why they thought the way they did. And the speeches or articles or letters which bore their names were more likely than not to be their own work-product. As a result, people listened when they spoke; these men did not need a "Meet the Press" format to obtain a public hearing. That this is not so today, it seems to me, is a singular loss to our society; but it is all the more reason for celebrating on this happy occasion the completion of the publication of the papers of Daniel Webster. Chief Justice WilliamRebnquist

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

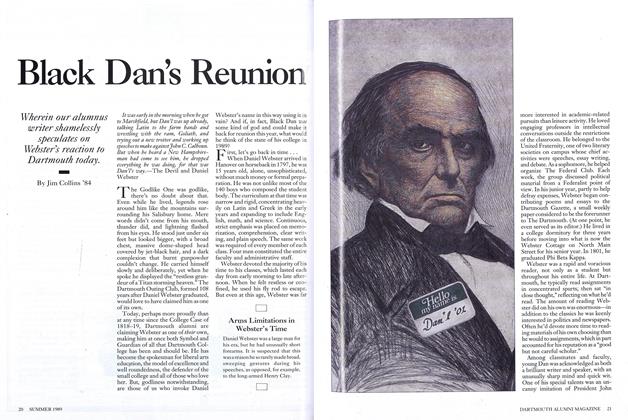

Cover StoryBlack Dan's Reunion

June 1989 By Jim Collins '84 -

Feature

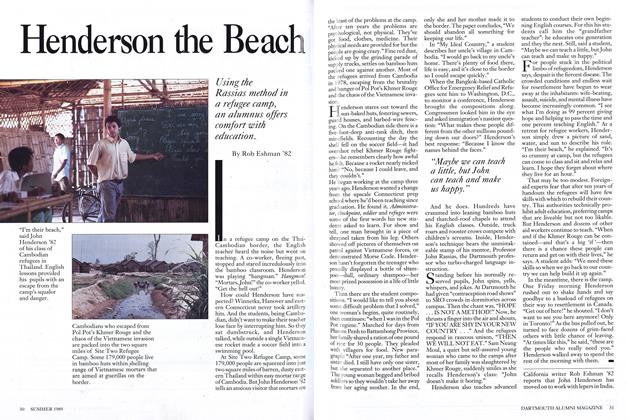

FeatureHenderson the Beach

June 1989 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Feature

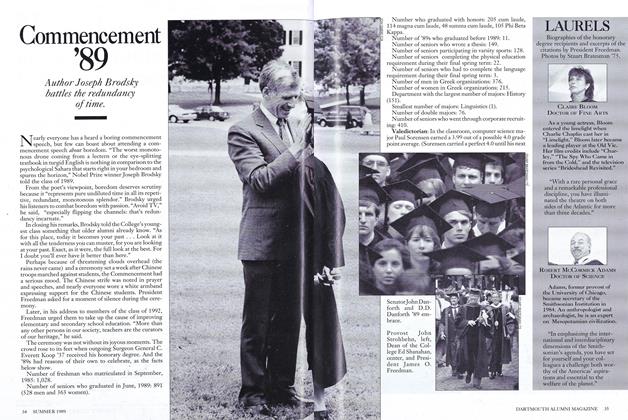

FeatureCommencement '89

June 1989 -

Feature

FeatureWebster's Greatest Monument

June 1989 By Ed -

Feature

FeatureHow I Invented Dog Running

June 1989 By John F. Anderson '34 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHIS HAT

June 1989