Or, why rhetoric should be taught today.

Here was a man who faced the thorniest moral dilemma in his nation's history. Should he oppose slavery or should he save the union? His answer was to support enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law, detested by his fellow New Englanders but required by the restive South. How, people asked him, could he sleep at night when abolitionists who once supported him now "libelled and abused" him for his stand?

"I have not lost a night's rest for a great many years from any such cause," the great man answered serenely. "I have some talent for sleeping."

A mere three months ago, Daniel Webster, class of 1801, was back on campus, in the form of historians and legal scholars—Chief Justice William Rehnquist among them. They were applauding publication by the University Press of New England of the 15 th and final volume of the Daniel Webster Papers. The quotation above was found there, among a vast store of thought and matchless argument.

The books are a work of scholarship positively Websterian in scope. During his lifetime, the Thunderous Presence argued over 200 cases before the Supreme Court-, served 27 years in the House and Senate, ran three times for the presidency, and worked 12-hour days in two terms as Secretary of State. The legal papers alone—feretted out of courthouses from New Hampshire to Washington—total more than 60,000 pages, all dutifully microfilmed (and mercifully edited down to two volumes). The editors also describe Webster's congressional output as "staggering." But in 2 2 years of compiling the man's papers, the editors—led by Dartmouth Professor of History Emeritus Charles Wiltse, and including History Professor Kenneth Shewmaker and assistant Alan Berolzheimer '79, among many others—didn't stagger.

The result is a political and rhetorical epic. The browser meets a debtridden gentleman farmer concerned about the state of his privies, a father who chides his son on his spelling and his wife on her purchases ("The honor of New England forbids us to send again to N.Y. for butter. Bonnets, you may get where you please.") Webster's autobiography, published in the first volume of his correspondence, recounts his boyhood, when he accidentally burned the family house down after a candlelit visit to the Farmer's Almanac. At Exeter Academy, Webster claims, he was too shy to speak in front of his schoolmates (". . . when my name was called & I saw all eyes turned to my seat, I could not raise myself from it.").

The young man would have done any Dartmouth parent proud. When in 1797 his father announced his intention to send the 15-year-old to the College, Daniel recalled later, "I remember that I was quite over come & my head grew dizzy. The thing appeared to me so high, & the expense and sacrifice it was to cost my father so great, I could only press his hands, & shed tears. Excellent, excellent parent!"

The papers are divided among four series: correspondence, speeches & formal writings, diplomatic papers, and legal papers. All are a casual readers' dream, but it is the speeches that offer the greatest delight to the layman. The man who could captivate audiences for three hours at a stretch left behind the texts of his greatest orations—works that should be studied by undergraduates as masterpieces of the woefully forgotten art of rhetoric.

They constitute a rich lode of history, but they shouldn't be left to historians alone. Together with Webster's letters and documents, the speeches reveal the genius of a leader who wrestled with his times and is doubtless sleeping at peace with himself to this day.

But Dartmouth and the nation need him too much to let him lie. The College invited Webster back to campus, and the following pages celebrate his presence.

In 22 years of scholarship, historian Charles Wiltse helped preserve Webster's immortality.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

Ed

Features

-

Feature

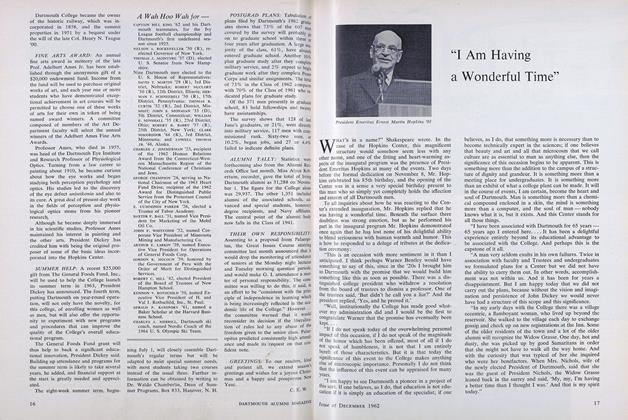

Feature"I Am Having a Wonderful Time"

DECEMBER 1962 -

Feature

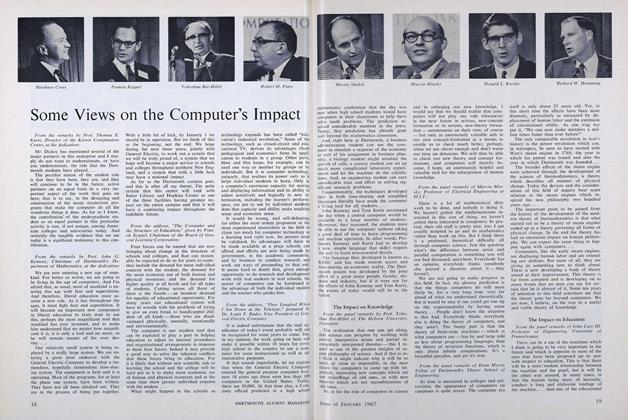

FeatureSome Views on the Computer's Impact

JANUARY 1967 -

Feature

FeatureSymphony Conductor

FEBRUARY 1972 -

Feature

FeatureThird Panel Discussion

October 1951 By ALLAN NEVINS -

Feature

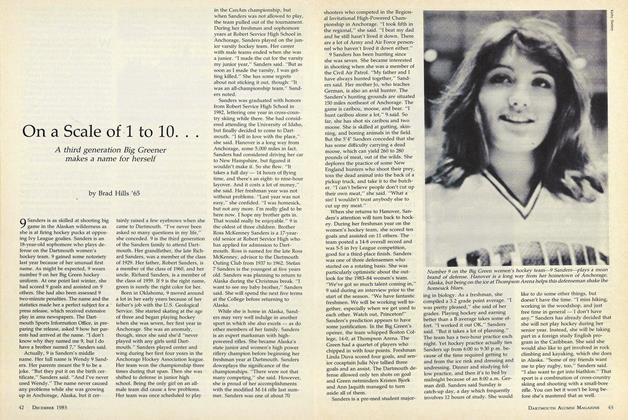

FeatureOn a Scale of 1 to 10...

DECEMBER 1983 By Brad Hills '65 -

Feature

Feature"Not So, Brothers and Friends"

October 1955 By JOHN FINCH, PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH