Where in our alumnus writer shamelessly speculates on Webster's reaction to Dartmouth today.

It was early in the morning when he got to Marsh field, but Dan'l was up already, talking Latin to the farm hands and wrestling with the ram, Goliath, and trying out a new trotter and working up speeches to make against John C. Calhoun. But when he heard a New Hampshireman had come to see him, he dropped everything he was doing, for that was Dan'l's way.—The Devil and Daniel Webster

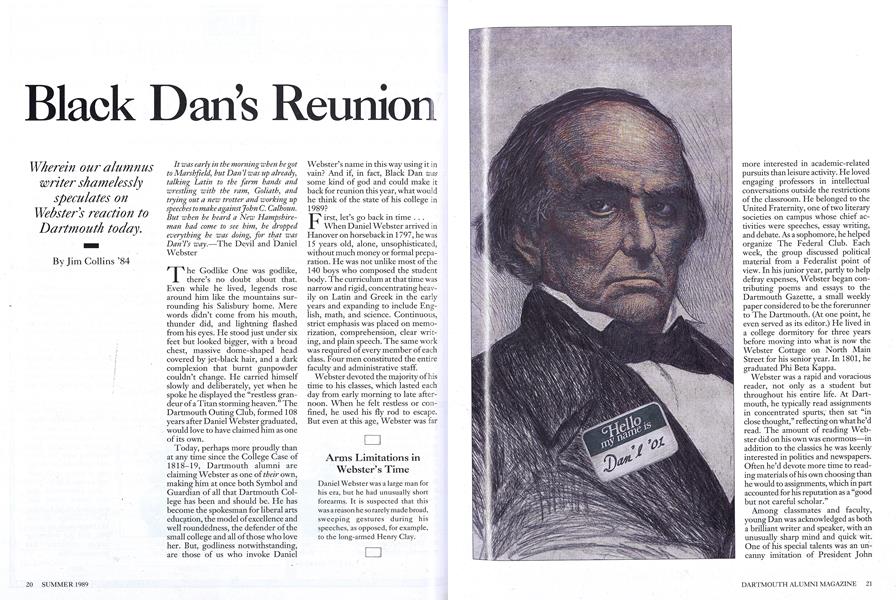

The Godlike One was godlike, there's no doubt about that. Even while he lived, legends rose around him like the mountains surrounding his Salisbury home. Mere words didn't come from his mouth, thunder did, and lightning flashed from his eyes. He stood just under six feet but looked bigger, with a broad chest, massive dome-shaped head covered by jet-black hair, and a dark complexion that burnt gunpowder couldn't change. He carried himself slowly and deliberately, yet when he spoke he displayed the "restless grandeur of a Titan storming heaven." The Dartmouth Outing Club, formed 108 years after Daniel Webster graduated, would love to have claimed him as one of its own.

Today, perhaps more proudly than at any time since the College Case of 1818-19, Dartmouth alumni are claiming Webster as one of their own, making him at once both Symbol and Guardian of all that Dartmouth College has been and should be. He has become the spokesman for liberal arts education, the model of excellence and well roundedness, the defender of the small college and all of those who love her. But, godliness notwithstanding, are those of us who invoke Daniel Webster's name in this way using it in vain? And if, in fact, Black Dan was some kind of god and could make it back for reunion this year, what would he think of the state of his college in 1989?

First, let's go back in time . . . When Daniel Webster arrived in Hanover on horseback in 1797, he was 15 years old, alone, unsophisticated, without much money or formal preparation. He was not unlike most of the 140 boys who composed the student body. The curriculum at that time was narrow and rigid, concentrating heavily on Latin and Greek in the early years and expanding to include English, math, and science. Continuous, strict emphasis was placed on memorization, comprehension, clear writing, and plain speech. The same work was required of every member of each class. Four men constituted the entire faculty and administrative staff.

Webster devoted the majority of his time to his classes, which lasted each day from early morning to late afternoon. When he felt restless or confined, he used his fly rod to escape. But even at this age, Webster was far more interested in academic-related pursuits than leisure activity. He loved engaging professors in intellectual conversations outside the restrictions of the classroom. He belonged to the United Fraternity, one of two literary societies on campus whose chief activities were speeches, essay writing, and debate. As a sophomore, he helped organize The Federal Club. Each week, the group discussed political material from a Federalist point of view. In his junior year, partly to help defray expenses, Webster began contributing poems and essays to the Dartmouth Gazette, a small weekly paper considered to be the forerunner to The Dartmouth. (At one point, he even served as its editor.) He lived in a college dormitory for three years before moving into what is now the Webster Cottage on North Main Street for his senior year. In 1801, he graduated Phi Beta Kappa.

Webster was a rapid and voracious reader, not only as a student but throughout his entire life. At Dartmouth, he typically read assignments in concentrated spurts,' then sat "in close thought," reflecting on what he'd read. The amount of reading Webster did on his own was enormous in addition to the classics he was keenly interested in politics and newspapers. Often he'd devote more time to reading materials of his own choosing than he would to assignments, which in part accounted for his reputation as a "good but not careful scholar."

Among classmates and faculty, young Dan was acknowledged as both a brilliant writer and speaker, with an unusually sharp mind and quick wit. One of his special talents was an uncanny imitation of President John Wheelock's slow, falsetto voice complete with the malapropisms that delighted the students behind Wheelock's back. Still, Webster's circle of intimate friends was quite small.

"He had an independent air and was rather careless in his dress and appearance," Webster's roommate wrote of him in 1797, "but he showed an intelligent look." Other classmates would mention Webster's aloofness, describing him as "pompous in his bearing and style," "ambitious, taking every opportunity to make himself conspicuous," "rather bombastic and always ready for a speech." Though his talents were respected, Webster was not universally popular in his class. Years later, Dartmouth Professor Edwin Sanborn remarked to the famous alumnus, "It is commonly reported that you did not study much at Dartmouth." Daniel Webster replied, "Sir, I studied and read more than all the rest of my class, if they had been made into one man! And I was as much above them then as I am now."

Still, Webster loved Dartmouth. He regarded his defense of the College in the Supreme Court case as his "favorite ever," he readily addressed alumni gatherings, and routinely traveled to Hanover to give orations or simply to see old friends during Commencement, usually held in August. Commencement is now held in the spring, of course, just one of the many differences between Daniel Webster's college and today's.

Today, Daniel Webster would not arrive in Hanover on horseback, and, given his stature, he would likely not be alone. Dropped off in front of the Hanover Inn after a comfortable ride, Webster would be struck by the changes brought by almost two centuries. And he'd be pleased at much of what he saw.

He would applaud the increasing emphasis on international studies especially the Japanese-language and Russian-exchange programs having strongly advocated international awareness and economic expansion while serving as Secretary of State. He'd be delighted to see students in the classroom being challenged by tasks other than rote memorization, and equally delighted to see so many discussion- and seminar-style classes with a small number of students to each professor. (Years after he'd graduated, Webster wrote of his dissatisfaction with the rigid and inadequate class instruction he had received at Dartmouth, preferring the numerous discussions he held with professors and classmates outside of the classroom.)

At the same time, however, Webster would be deeply concerned about the general curriculum's shift away from pure liberal arts. He would be especially saddened by the diminishing importance of speech and rhetoric in the undergraduate program (though happy to hear that Dartmouth's competitive debating team is consistently among the nation's top). If pressed, he would afgue against large increases in specialized programs and studies areas. (He was a strong believer in classical training; he once gave an oration that warned against fashion in opinion and thought, recommending Plato and the ancients over Hume and his contemporaries.)

He would be interested to learn of the tendency of the student body toward business and practical training. In the classes Webster knew, 41 percent of Dartmouth's graduates went on to be lawyers, 25 percent joined the ministry, 12 percent became teachers, eight percent physicians, and only six percent went into business. Webster was himself an authority on banking and economics and struggled his whole life to support heavy debt and an expensive lifestyle. He would understand the motives.

Webster would look at the current year-round plan of operation as a perfect topic for debate, recognizing the foreign learning and opportunities it affords, but eventually coming down on the side of longer semesters with more time for reading and reflection. The current size of the student body would make another good debate topic for Webster, who would realize the balance between personalized learning and extent of resources and facilities. (How he'd love Baker Library!) During Webster's time, Dartmouth graduated an average of 36 seniors a year—a small number today, but then the second-highest in the nation behind Harvard. The subject of Dartmouth's professional schools also would intrigue him (as a junior, he had signed up for Dartmouth's pre-med training before he decided on law as a career.) And while Webster was a conservative man, he was a well-known risk-taker when new financial opportunities presented themselves. Touring the new engineering facilities at Thayer (and hearing of Tuck's joint program with Japan), we can almost see his mind racing to keep up with the investment possibilities.

When talk shifted to the current affairs of 1989, Webster's dark eyes would light up as he noted President Freedman's fine legal background and reasoned, articulate oratory. He'd stand behind the new president's vision of Dartmouth as a more comfortable place for creative loners (Webster having been one, in many ways, himself) and a place of increased intellectualism. On the subject of fraternities, Webster would passionately defend their existence. His closest college friendships came through his own fraternity—and his fondness for drinking was well chronicled. At the same time, Webster would endorse the College's position that fraternities become more focused on academic and intellectual activities, adding as they would to extracurricular education.

The outdoors-loving Webster would likely argue on the pro side for continuing freshman trips in their current form. But, remembering his own humble background and preparation, he would probably oppose distinguishing Presidential Scholars during their first year on campus.

When the talk turned to polarization of the Dartmouth community, though, Black Dan's eyes would start to smoulder and his voice begin to ring. Having struggled most of his life to save a nation divided against itself, Webster would deplore those forces threatening to do the same to his alma mater. He would argue strongly for moderation on all sides, but also for all of the rights and freedoms guaranteed by the Constitution. Himself a model of responsible conservatism, Webster would staunchly defend The Dartmouth Review's right to publish, but would harshly denounce much of what he saw published there. (Webster once reflected on his own political writings in college, criticizing them as "sufficiently boyish...l had not then learned that all true power in writing is in the idea, not in the style.") He would similarly denounce any double standards in punishing offenders of Dartmouth's codes and principles; a discrepency, he would say, would increase the dangers of sectionalism and disunity within the community.

The possibility of a permanently divided community, Daniel Webster would argue, is the greatest threat facing Dartmouth College today. It is a threat that can only be relieved through reason and compromise and love of the greater good. The issues surrounding that threat being of philosophical and debatable natureare best worked out, may only be worked out, through intelligent public discourse.

One thing is certain. Webster would not be idle at his reunion. Between receptions he'd find a table downtown where he could continue working out his peace proposal for the Middle East; his light at the Inn would burn into the night as he prepared notes for an address to the United Nations. Earlymorning joggers would pass him near the Green, his fly rod in hand, heading out to see if the trout were still biting in the White River. But if any member of the Dartmouth family approached him to debate one of the day's issues, Webster would have dropped everything he was doing. For that was Dan'l's way.

We editors are often accused of quoting people out of context, but in this case the crime may seem especially egregious. Who are we to be interviewing a man who's been dead 157 years? Our answer is that the quotations below, taken from the Webster Papers, prove that Black Dan still lives.

Let's begin, sir, with the federal deficit:how do you feel about the nation's finances?

What a picture do they exhibit of the wisdom and prudence and foresight of Government. "The revenue of a State," says a profound writer, "is the State." [Excerpted from Webster's speech before Congress on the Conscription Bill, 1814]

Tell us about your stand on free trade, acause espoused by many conservatives today.

Protection.... of our own labor against ... cheaper, ill-paid, half-fed and pauper labor...is, in my opinion, a duty which the country owes to its own citizens. I am, therefore, decidedly, for protecting our own industry and our own labor. [Speech before a reception in New York, 1837]

You must have followed the Oliver Northtrial. Many people say the man is a patriotwho acted in his nation's best interest.

It may be very possible that good intentions do really sometimes exist when constitutional restraints are disregarded. There are men; in all ages, who mean to exercise power usefully; but who mean to exercise it. They mean to govern well; but they mean to govern. They promise to be kind masters; but they mean to be masters. They think there need be but little restraint upon themselves. Their notion of the public interest is apt to be quite closely connected with their own exercise of authority. They may not, indeed, always understand their own motives. The love of power may sink too deep in their own hearts even for their own scrutiny, and may pass with themselves for mere patriotism and benevolence. [Reception in New York, 1837]

And Jim Wright? Should his personaldealings have been dragged into the limelight? Or should public figures be protectedfrom such scrutiny?

A public man has no occasion to be embarassed, if he is honest. Himself and his feelings should be to him as nobody and as nothing; the interest of his country must be to him as every thing; he must sink what is personal to himself, making exertions for his country; and it is his ability and readiness to do this which are to mark him as a great or as a little man in time to come. [Reception in Boston, 1842]

You've already been generous with yourtime. But a final question on your belovedalma mater. How do you feel about TheDartmouth Review and its undergraduateeditors?

They think that he who talks loudest reasons best. And this we must expect, when the press is free, as it is here, and I trust always will be; for, with all its licentiousness and all its evil, the entire and absolute freedom of the press is essential to the preservation of government on the basis of a free constitution. [Senate speech on "The Constitution and the Union," 1850]

HIS MOTHER

Jim Collins '84 is co-founder with several other Dartmouth alumni of The Devil and Daniel Webster Society. Once a year the group travels to a wild place and reads Stephen Vincent Benet's book out loud.

"That governmentis most secureagainst the dangerof popular commotionwhich is itselfentirely popular

I go for theConstitution asit is, and for theUnion as it is."

"I can bear hisabuse, but if heundertakes mycommendation Ibegin to tremblefor myreputation."

Jim Collins '84

-

Article

ArticleBaseball and the Pursuit of Innocence

June 1995 By Jim Collins '84 -

Feature

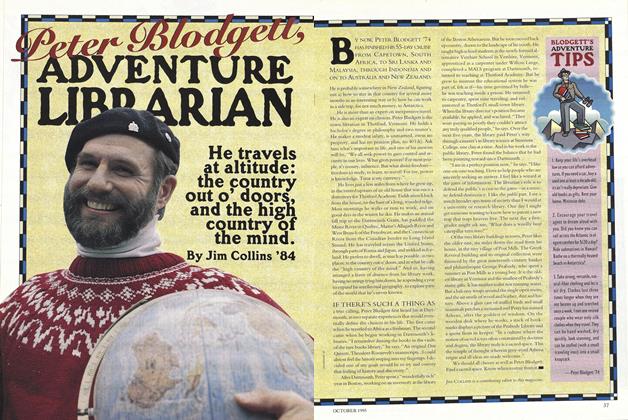

FeaturePeter Blodgutt, Adventure Librarian

October 1995 By Jim Collins '84 -

Feature

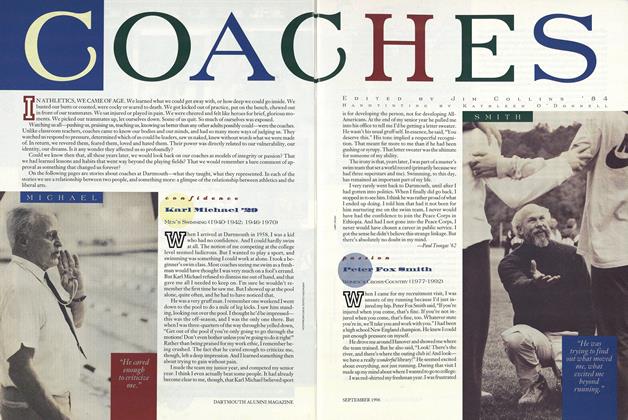

FeatureCOACHES

SEPTEMBER 1996 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

Article

ArticleLandscapes of Murder

APRIL 1997 By Jim Collins '84 -

Cover Story

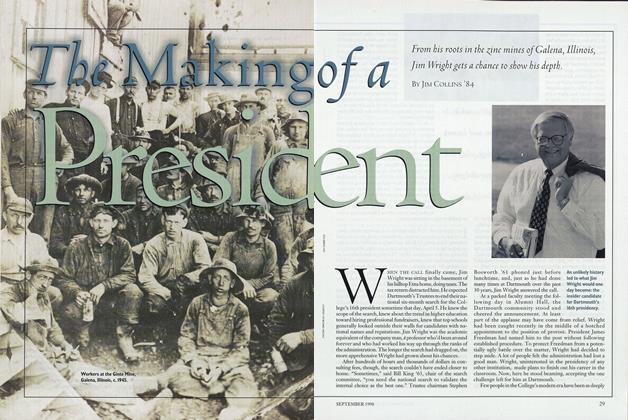

Cover StoryThe Making of a President

SEPTEMBER 1998 By Jim Collins '84 -

Sports

SportsMoneyball

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2021 By JIM COLLINS '84

Features

-

Feature

FeatureTHE HUNTERS, OR THE SUFFERINGS OF HUGH AND FRANCIS, IN THE WILDERNESS.

January 1975 -

Feature

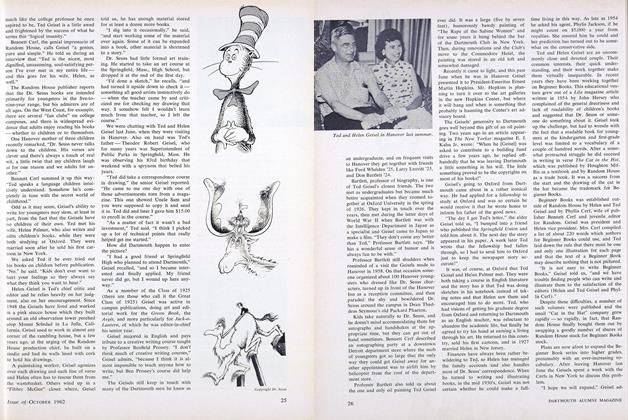

FeatureDr. Seuss

OCTOBER 1962 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

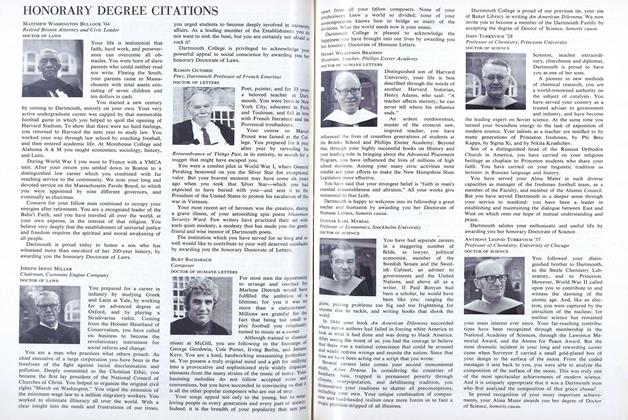

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

JULY 1971 By honoris causa. -

Feature

FeatureMy "Most Unforgettable Character"

February 1954 By JAMES L. MONTAGUE '28 -

Feature

FeatureHanover in the Ice Age

November 1957 By RICHARD J. LOUGEE '27