Using the Rassias method in a refugee camp, an alumnus offers comfort with education.

In a refugee camp on the Thai-Cambodian border, the English teacher heard the noise but went on teaching. A co-worker, fleeing past, stopped and stared incredulously into the bamboo classroom. Henderson was playing "hangman." Hangman! "Mortars, John!" the co-worker yelled. "Get the hell out!"

How could Henderson have suspected? Winnetka, Hanover and eastern Connecticut never took artillery hits. And the students, being Cambodian, didn't want to make their teacher lose face by interrupting him. So they sat dumbstruck, and Henderson talked, while outside a single Vietnamese rocket made a soccer field into a swimming pool.

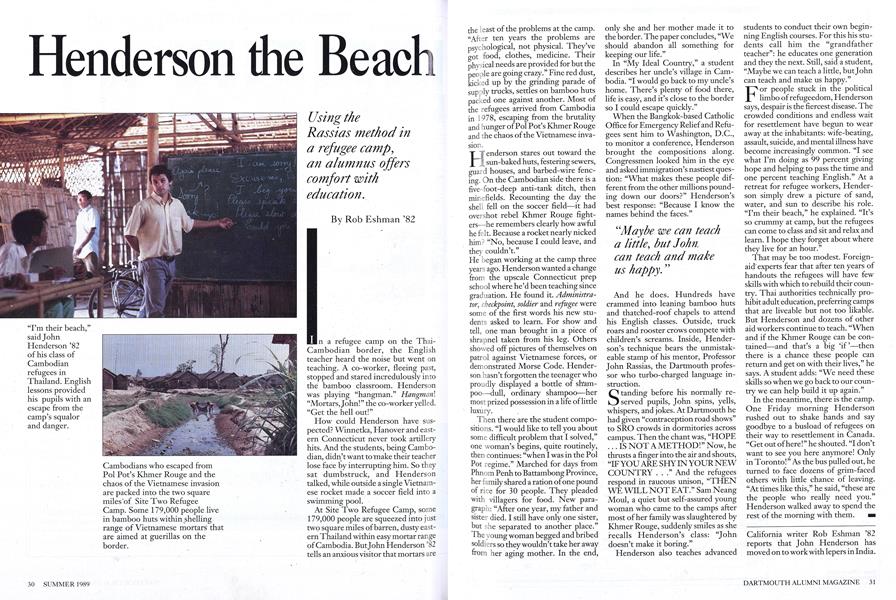

At Site Two Refugee Camp, some 179,000 people are squeezed into just two square miles of barren, dusty eastern Thailand within easy mortar range of Cambodia. But John Henderson '82 tells an anxious visitor that mortars are the least of the problems at the camp. "After ten years the problems are psychological, not physical. They've got food, clothes, medicine. Their physical needs are provided for but the people are going crazy." Fine red dust, kicked up by the grinding parade of supply tracks, settles on bamboo huts packed one against another. Most of the refugees arrived from Cambodia in 1978, escaping from the brutality and hunger of Pol Pot's Khmer Rouge and the chaos of the Vietnamese invasion.

Henderson stares out toward the sun-baked huts, festering sewers, guard houses, and barbed-wire fencing. On the Cambodian side there is a five-foot-deep anti-tank ditch, then minefields. Recounting the day the shell fell on the soccer field it had overshot rebel Khmer Rouge fighters he remembers clearly how awful he felt. Because a rocket nearly nicked him? "No, because I could leave, and they couldn't."

He began working at the camp three years ago. Henderson wanted a change from the upscale Connecticut prep school where he'd been teaching since graduation. He found it. Administrator, checkpoint, soldier and refugee were some of the first words his new students asked to learn. For show and tell, one man brought in a piece of shrapnel taken from his leg. Others showed off pictures of themselves on patrol against Vietnamese forces, or demonstrated Morse Code. Henderson hasn't forgotten the teenager who proudly displayed a bottle of shampoo dull, ordinary shampoo her most prized possession in a life of little luxury.

Then there are the student compositions. "I would like to tell you about some difficult problem that I solved," one woman's begins, quite routinely, then continues: "when I was in the Pol Pot regime." Marched for days from Phnom Penh to Battambong Province, her family shared a ration of one pound of rice for 30 people. They pleaded with villagers for food. New paragraph: "After one year, my father and sister died. I still have only one sister, but she separated to another place." The young woman begged and bribed soldiers so they wouldn't take her away from her aging mother. In the end, only she and her mother made it to the border. The paper concludes, "We should abandon all something for keeping our life."

In "My Ideal Country," a student describes her uncle's village in Cambodia. "I would go back to my uncle's home. There's plenty of food there, life is easy, and it's close to the border so I could escape quickly."

When the Bangkok-based Catholic Office for Emergency Relief and Refugees sent him to Washington, D.C., to monitor a conference, Henderson brought the compositions along. Congressmen looked him in the eye and asked immigration's nastiest question: "What makes these people different from the other millions pounding down our doors?" Henderson's best response: "Because I know the names behind the faces."

And he does. Hundreds have crammed into leaning bamboo huts and thatched-roof chapels to attend his English classes. Outside, truck roars and rooster crows compete with children's screams. Inside, Henderson's technique bears the unmistakeable stamp of his mentor, Professor John Rassias, the Dartmouth professor who turbo-charged language instruction.

Standing before his normally reserved pupils, John spins, yells, whispers, and jokes. At Dartmouth he had given "contraception road shows" to SRO crowds in dormitories across campus. Then the chant was, "HOPE ... IS NOT A METHOD!" Now, he thrusts a finger into the air and shouts, "IF YOU ARE SHY IN YOUR NEW COUNTRY ..." And the refugees respond in raucous unison, "THEN WE WILL NOT EAT." Sam Neang Moul, a quiet but self-assured young woman who came to the camps after most of her family was slaughtered by Khmer Rouge, suddenly smiles as she recalls Henderson's class: "John doesn't make it boring."

Henderson also teaches advanced students to conduct their own beginning English courses. For this his students call him the "grandfather teacher": he educates one generation and they the next. Still, said a student, "Maybe we can teach a little, but John can teach and make us happy."

For people stuck in the political limbo of refugeedom, Henderson says, despair is the fiercest disease. The crowded conditions and endless wait for resettlement have begun to wear away at the inhabitants: wife-beating, assault, suicide, and mental illness have become increasingly common. "I see what I'm doing as 99 percent giving hope and helping to pass the time and one percent teaching English." At a retreat for refugee workers, Henderson simply drew a picture of sand, water, and sun to describe his role. "I'm their beach," he explained. "It's so crummy at camp, but the refugees can come to class and sit and relax and learn. I hope they forget about where they live for an hour."

That may be too modest. Foreignaid experts fear that after ten years of handouts the refugees will have few skills with which to rebuild their country. Thai authorities technically prohibit adult education, preferring camps that are liveable but not too likable. But Henderson and dozens of other aid workers continue to teach. "When and if the Khmer Rouge can be contained and that's a big 'if' then there is a chance these people can return and get on with their lives," he says. A student adds: "We need these skills so when we go back to our country we can help build it up again."

In the meantime, there is the camp. One Friday morning Henderson rushed out to shake hands and say goodbye to a busload of refugees on their way to resetdement in Canada. "Get out of here!" he shouted. "I don't want to see you here anymore! Only in Toronto!" As the bus pulled out, he turned to face dozens of grim-faced others with litde chance of leaving. "At times like this," he said, "these are the people who really need you." Henderson walked away to spend the rest of the morning with them.

Cambodians who escaped from Pol Pot's Khmer Rouge and the chaos of the Vietnamese invasion are packed into the two square miles of Site Two Refugee Camp. Some 179,000 people live in bamboo huts within shelling range of Vietnamese mortars that are aimed at guerillas on the border.

California writer Rob Eshman '82 reports that John Henderson has moved on to work with lepers in India.

"Maybe we can teacha little, but John,can teach and makeus happy."

Rob Eshman '82

-

Article

ArticleA Time Away

OCTOBER 1981 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Article

ArticleA Skeptic in Simian Clothing

DECEMBER 1981 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Article

ArticleTo Play Is to Lose

DECEMBER 1981 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Feature

FeatureThe Credits

November 1982 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Feature

FeatureShrink Rap

NOVEMBER 1990 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Ascent of Korey

MARCH 1995 By Rob Eshman '82

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Right Man at the Right Time

NOVEMBER • 1987 -

Feature

FeatureThree in the Theater

APRIL 1971 By BARBARA BLOUGH -

Feature

FeaturePiano Man

July/August 2011 By ERIC TUCKER -

Feature

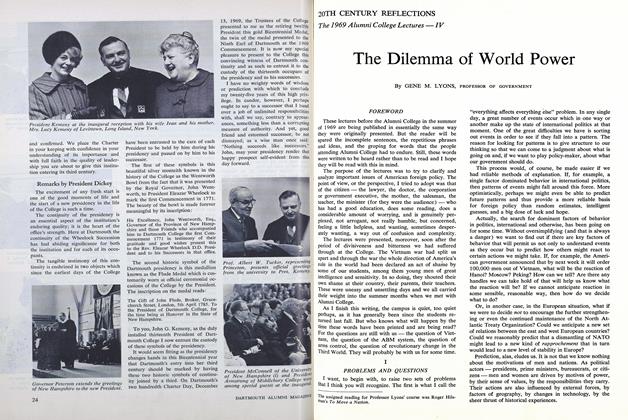

FeatureThe Dilemma of World Power

APRIL 1970 By GENE M. LYONS -

Feature

FeatureThe Boom in Off-Campus Study

NOVEMBER 1970 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

Featurenotebook

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2016 By LAURA DECAPUA PHOTOGRAPHY/TUCK