Calvert: Jules Verne, 20,000 LeaguesUnder the Sea, 1870. (Airmont and many other editions). Juvenile narrative, but a crucial book. (The sf film equivalent is Planet ofthe Apes) Verne invented the sf genre and linked it to other fine literature when 20,000Leagues closely imitated Moby Dick. Verne copied Melville's hero's wilderness wandering—a false action, when what matters is author lecturing reader: Melville on metaphysics and whaling, Verne on society's evils, submarine biology, and Nautilus's electrical engines.

Perrin: I see the historical importance of Verne, but would fight hard to keep any of his juvenile books out of our sf course.

Perrin: Edward Bellamy, LookingBackward, 1888 (Signet and many other editions). A rich young Bostonian insomniac has to be hypnotized to get to sleep. One night his mansion burns while he's in hypno-sleep in a soundproof concrete vault under, the basement. He's presumed dead. An attractive woman awakens him in 2 000 A.D. This best-seller of the 1880s (it even brought a new political party into being) is an account of what Massachusetts and indeed the whole world—could be like 11 years from now. Feeble plot, stunning ideas.

Calvert: Few enjoy Bellamy's style, but he'll still be with you in five years.

Calvert: E. M. Forster, "The Machine Stops," in The Eternal Moment, 1909 (Harvest). A dehumanized, computerized, subterranean world, but Kuno wonders what's above (metaphysics again). The trouble starts when "the machine" stops, cutting off all human services, from oxygen to companionship. Dante imagined it 67 5 years ago, but the future is now: Time magazine reports Japanese plans for subterranean cities.

Perrin: Along with Aldous Huxley and Doris Lessing, E. M. Forster is one of the handful of mainstream authors to have written good science fiction. You can read this novella in less than an hour. Do.

Calvert: Arthur C. Clarke, The Cityand the Stars, 1956 (Signet). Alvin, the 15th Unique (a really new human being), protects the human race from an entirely computerized existence. A seductive story, at its best when explaining the importance of children in humanity's renewal.

Perrin: I suspect this is a book Marvin Minsky would hate, although Clarke is a fellow scientist. Me, I love it.

Perrin: Walter M. Mil lerJ r.,A Canticlefor Leibowitz, 1961 (Bantam). Connoisseur has a series on the best this and that: best wine, best coffee, best hotel in Australia. They once asked me to write a piece on the best sf novel. I unhesitatingly picked Canticle.

Calvert: Miller's literary models include the King James Bible and Shakespeare's King Lear. For sheer apocalyptic intensity and pathos, few other works can touch it. Got time for one sf novel? This is it.

Perrin: Samuel Delany, "We in Some Strange Power's Employ, Move on a Rigorous Line," in Driftglass, 1968 (Signet). This wonderful short story is by the first major black sf writer to emerge. The story works on five or six levels, including one where he is teasing his fellow sf writer Roger Zelazny and another where he is playing off Spenser's The Faerie Queen.

Calvert: You'll love the Hell's Angels (Devils) on flying cycles. A six-level novella can be a little thin on plot and character. This one is, but it substitutes something missing in much sf: a genuine sense of humor.

Perrin: Ursula LeGu, TheLefiHandof Darkness, 1969 (Ace-Charter). Along with Miller, LeGuin is at the pinnacle of American sf. Left Hand is one of her best. It's entirely about sex. Rather unusual sex, far in the future. Not kinky, not pornographic, just unusual.

Calvert: Despite the inherently interesting topic, the book can be dull. Poe's The Narrative of A. Gordon Pym is better, despite no sex.

Calvert: John Brunner, The Shockwave Rider, 1975 (Ballantine). Wonder what the world will be like when computers control so much that a world-class hacker can create and recreate himself at will? The most realistic sf novel of this moment, set only a few years into our future.

Perrin: Anyone who faxes things or owns a computer ought to read it.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

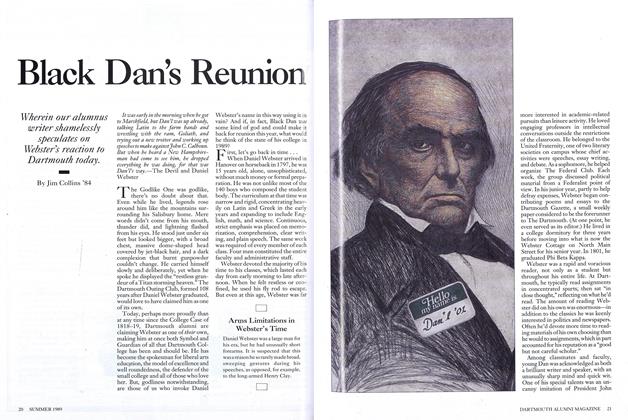

Cover StoryBlack Dan's Reunion

June 1989 By Jim Collins '84 -

Feature

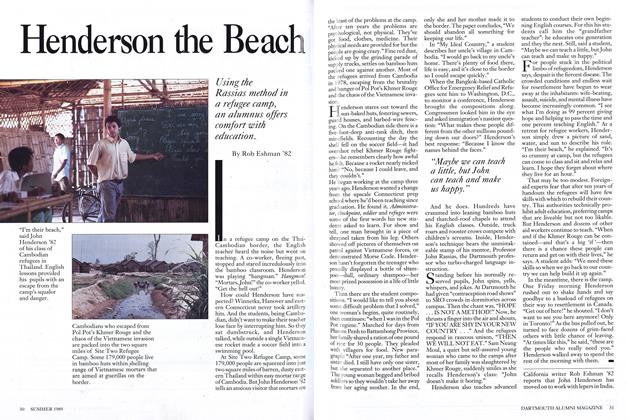

FeatureHenderson the Beach

June 1989 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Feature

FeatureCommencement '89

June 1989 -

Feature

FeatureWebster's Greatest Monument

June 1989 By Ed -

Feature

FeatureHow I Invented Dog Running

June 1989 By John F. Anderson '34 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHIS HAT

June 1989