Grounded in frontier fears, "apartness" is a myth made real.

Many students begin my course on the history of modern South Africa knowing little about that "beautiful but troubled land," as Alan Paton described his country, except that it is involved in a struggle between a powerful white minority determined to maintain its political and economic supremacy under apartheid, and a disenfranchised black majority calling for the vote and a more equitable share of South Africa's immense resources and wealth. Other students come to the course puzzled by questions raised in protest campaigns urging divestment and demanding sanctions against the apartheid regime.

Apartheid, as originally conceived by Afrikaners descendants of the 17th-century Dutch, German, and French Huguenot settlers at the Cape of Good Hope was defined in the 1948 Election Manifesto of the National Party as "a policy which sets itself the task of preserving and safeguarding the racial identity of the white population of the country." The electoral success of the National Party marked the political triumph of three million Afrikaners over two million persons of British descent the rival white settler group in South Africa. The election also marked the continuing denial of the citizenship rights of 28 million black Africans, Asians, and persons of mixed racial background.

Although the term "apartheid" itself is of relatively recent vintage, the roots of the apartheid ideology are deeply embedded in three centuries of South African history.

Within a single generation of the original Dutch settlement at the Cape in the 17 th century, the notion that all masters were white and all servants black was already firmly implanted and accepted among the Boers, forebears of the Afrikaners. But it was the settlers' frontier experience that had the most profound influence in shaping the Afrikaners' folk mythology and racial ideology. Groups of Boers who sought new lands away from the restrictions imposed by Dutch (later British) metropolitan authorities initially encountered little difficulty in breaking through the resistance put up by indigenous hunting and herding societies in the western Cape area. In the 17705, however, at the Great Fish and Bushman's Rivers, the Boers for the first time ran smack into the more powerfully organized Bantuspeaking Africans the ancestors of the present-day black majority in South Africa. This was the beginning of the so-called "hard frontier" era, which lasted until the mid-1830s. It was a time of bitter though largely inconclusive wars with black African kingdoms and of Boer struggles against the extension of official metropolitan control and authority.

It was during the friction and warfare of the hard frontier era that the Boers evolved a historical myth to support their predicament—a myth that has survived to this day in the ideology of apartheid. The central symbol of this myth is the laager, a fortresslike ring of wagons within which frontiersmen gathered their kinfolk for protection against intrusion from the "savages" beyond. From the perspective of contemporary history, perhaps the most significant characteristic of this myth is its definition of black Africans as "the enemy on the other side of the frontier" as an alien group outside of society, useful as temporary labor under strict control, but to be kept outside of the laager at all costs if the survival of the Afrikaner people and their way of life was to be ensured. It is the endurance of this myth in the ideology of apartheid which enables the present-day descendants of the Boers to feel satisfied with a system that disenfranchises black Africans, moves entire townships arbitrarily from one place to another, restricts the movement of labor-seekers, and treats the vast majority of the population as aliens in the 87 percent of the South African territory defined as belonging to the whites.

My course syllabus focuses on three related themes. It surveys the history of race relations in South Africa, examines similarities and differences between the evolution of white-supremacy ideas and practices in South Africa and our own country, and looks at how South Africa's history is being played out in the contemporary struggles between the country's black majority and white rulers. Many of the books listed below are used by my students. I recommend the readings to you.

History Professor Leo Spitzer.

I ronically, History Professor Leo Spitzer has spent the last two decades studying and teaching about South Africa, but he has never been allowed into that nation. In the early 19605, Spitzer made plans to conduct doctoral research in South Africa. The project, an intellectual history of the Xhosa people of South Africa, received funding from the Ford Foundation. But the South African government, still smarting from the repercussions from the Sharpeville Massacre, refused to grant Spitzer a research visa. The professor recalls' that although he was intensely disappointed and frustrated at being denied a visa, he was not surprised. "At the time, I was studying at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, which was a center for South African studies and anti-apartheid efforts," he says. "I had been studying under A.C. Jordan, a black South African novelist who was in exile. I was involved in antiapartheid activities. Of course the South African government did not want someone like me to conduct research in the country, especially when the research was to focus on one of the black cultures. " Instead, Spitzer went to western Africa to study the Creoles of Sierra Leone. But despite having written a dissertation and a book on the Creoles, Spitzer has remained fascinated by South Africa. The professor explains that his empathy with Third World nations derives from his own past. Born and raised in Bolivia after his parents fled Nazi-torn Austria, he says, "I often wonder what it would have been like if my parents had emigrated to South Africa, as many Jews did at the time." Spitzer came to the United States at the age of ten. He majored in European literature at Brandeis University. After earning an M. A. in Latin American history at the University of Wisonsin, he took a literature course from Jordan. The novelist's The Wrath of the Ancestors inspired Spitzer to pursue the language and history of the Xhosa South Africans. Spitzer's background in literature enriches his teaching of South African history. "Novels and autobiographies expose aspects of consciousness not gotten to in other history texts," he says." They give a sense of place and raise debate." Among his assigned reading: Nadine Gordimer's July's People, Ellen Kuzwayo's Call Me Woman, and Bloke Modisane's Blame Me on History. Karen Endicott

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

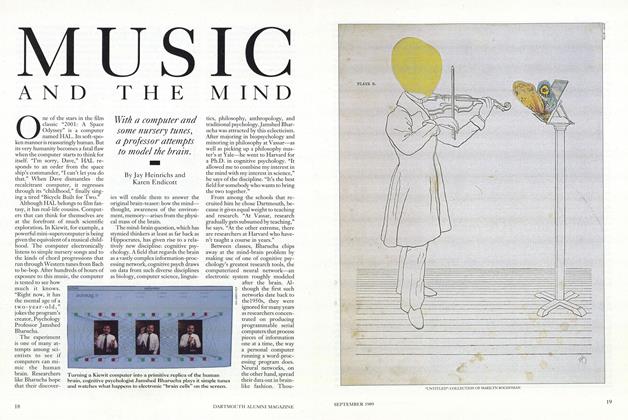

Cover StoryMUSIC AND THE MIND

September 1989 By Jay Heinrichs and Karen Endicott -

Feature

FeatureA Cure for Nostalgia: the Ultimate Comp Exam

September 1989 By Nancy Staab '90 -

Feature

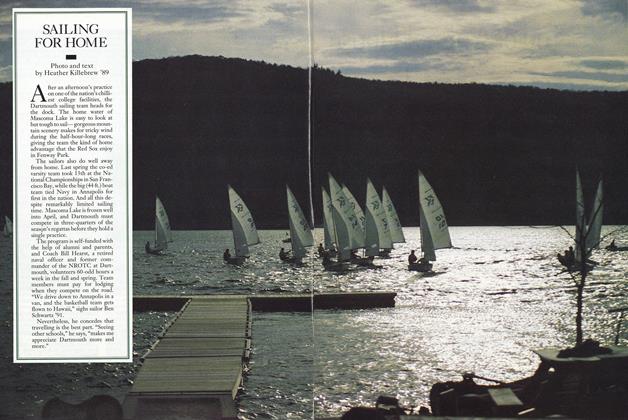

FeatureSAILING FOR HOME

September 1989 By Heather Killebrew '89 -

Feature

FeatureSon of Animal House

September 1989 By Ed. -

Article

ArticleThe man who wrote the movie returns to find brothers in slime.

September 1989 By Chris Miller '63 -

Article

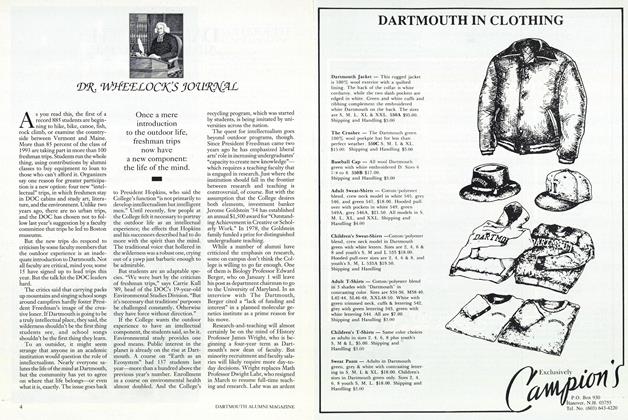

ArticleDR WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

September 1989