They called me Dartmouth's Problem Solver. That may sound crazy to you what problems (except for the notorious political ones) need solving in the little village of Hanover?

You'd be amazed. During my year as an associate editor and columnist for The Dartmouth, I was a busy man. Each week I answered students' cries for help or information on any facet of life at the College, from the height of the president's basketball net to the indoor habits of skunks. My column (called, naturally, "The Problem Solver") was read by a campus riddled with controversy over South Africa, fraternities, and free-speech rights. But I dealt with the really important issues, the ones that tie people together, that let people know what they have in common, such as the belief that the Problem Solver was crazy.

lake the president's basketball court. Last spring I received a letter from the president of Sigma Nu fraternity, Ted Carleton '9O, complaining that James O. Freedman's hoop, situated in a corner of the presidential driveway, was not of regulation height. I immediately decided that Ted had a problem worthy of investigation. Although many students complain that the president can be tough to find, I had no problem reaching him during his weekly student office hours and explaining the problem. The Sigma Nus, as well as several other students, have been using the court at the president's house over the years, because of its convenient location on Webster Avenue's Fraternity Row. Ted had complained that "not only is the hoop not of regulation height, but the garage is too close to the basket, and the branches need to be trimmed on the other side." He also wanted President Freedman to remove the fence behind the basket to allow players to drive to the hoop, and he requested that the president level the driveway.

I wasn't sure what to expect from an Ivy League head who rubs elbows with the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court and appears on David Brinkley. But, to my surprise, President Freedman did not look fazed by my request. In fact, he said of the basketball net, "We checked it when we first moved in." He told me that the basket "gets a lot of use," and that he and his son Jared, a Harvard undergraduate, "go out in the off hours" to shoot some hoops.

He encouraged me to go measure the basket myself, and added that, if it were not truly regulation height, I should go ahead and have the Buildings & Grounds department fix it.

After confirming with the National Basketball Association that the official height of a basket is indeed ten feet (journalists must always check their facts), I went over to President Freedman's house with a friend and Problem Solver contributor, Gary Katz '90, to measure the hoop. Much to our horror, we found that the basket was indeed too high, and it drooped ranging from one to three and a half inches over regulation height. My next column in the paper uncovered the whole incredible story. Just to make it official, I also sent a memo over to B&G stating my findings and President Freedman's desire to rectify the situation as soon as possible.

Two months later, nothing had been done. Eventually, though, the local Valley News picked up on the story, and I finally found Jay Bliss, associate director of Buildings & Grounds, just back from a month-long vacation. He put a rush order on the project. "I kicked a little rear end and it's gonna be done real soon," he assured me. And indeed it was. The hoop is now the perfect height though the driveway is a little uneven, the garage has not been moved, and players who drive to the hoop commit an offensive foul on the president's fence.

A second presidential problem was tougher to crack. Last January the International Students Association unsuccessfully proposed to change the name of its headquarters from the Nathan Lord House to the Fidel Castro International Center. One of many concerned students asked me to find out how President Castro felt about it. First I called the State Department in Washington. "I would never have expected that of Dartmouth," an official said in response to the proposal. I then tried to place a call to Cuba, but was told by AT&T international operator number 107 that only a member of the U.S. government could do that. In the end I had to settle for a reaction from the Cuban cultural and press attache's secretary in Washington. "Yes, of course," she said, she certainly thought Castro would be honored by the International Students Association's move.

My work took me high (the State Department) and low one student, Lisa Verb '90, contacted me because she was too short to reach her Hinman mailbox. "If I have any mail, I have to jump up to see eye level with the door," she wrote. After many tries, I was finally able to locate the precise person in the Dartmouth bureaucracy who was entrusted with the power to change students' Hinman boxes, the Office of Residential Life's housing assignment coordinator. The box was changed.

Then there was the student who asked why the quality of toilet paper was lower in the dorms than in other buildings on campus. For this problem, I called the College's director of purchasing, George Newkirk Sr., who informed me that he buys only one type of toilet paper and has been buying it for the past 17 years. Greg Corrigan '92, who worked during the summer as a computer consultant for the company that manufactures the College's toilet paper, got me in touch with a company representative who informed me that the paper was its second-lowest grade. I then found that Thayer Dining Hall did indeed use a twoply toilet paper rather than the one-ply brand used in the dorms. No one wanted to comment about the discrepancy in quality, but a doctor at Dick's House said that he has never heard of any complaints from students resulting from the use of the paper in the dorms.

I even did windows. One student, Michael Reynolds '90, complained that a broken pane in his dorm room had not been fixed in two months. (At the time, Michael was editor in chief of The Dartmouth so much for the editorship being a position of influence.) After a couple of calls to the right people, and mention of the problem in the paper, the bureaucratic wheels began moving and the window was repaired.

And when Meredith Katz '90 complained that skunks were spraying dogs who would then enter Richardson dormitory and chase partying students outside, I let this distraught student know that she was not alone. I found out that a skunk had invaded the office of Tucker Foundation Dean James Breeden '56 last summer. "He's a cutie, he really is," Administrative Assistant Mickie Rosenstein said, in reference to the skunk.

I guess the bottom line of all this problem solving is that the press at Dartmouth really can make a difference. "Frankly," Buildings & Grounds' Mr. Bliss told me about Freedman's basketball hoop, "when things get this kind of publicity I like to get them out of my hair." a

When Problem Solver Aronsohn heard that President Freedman's basketball hoop was out of kilter, he chose to go straight to the top.

Aronsohn once did some research into why the Green isn't always green.

When government major John Aronsohn wrote this essay, graduation loomed and he was working on solving his most difficult problem to date: finding a job. In the meantime, readers who would like to see more of his prose can read the 1990 class column. As the newly elected secretary, John will be writing it for at least the next five years.

Toilet tissue too tough? Mailbox too tall? This was the guy to call.

After the proposal to change the name of the Nathan Lord House, one of many concerted students asked me to find out how President Castro felt about it."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

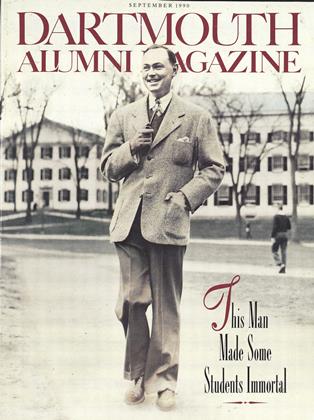

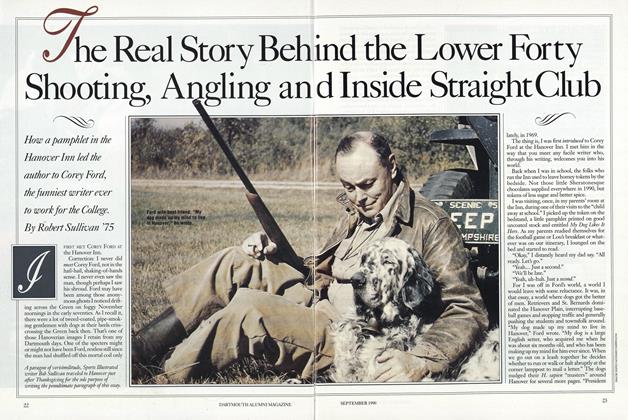

FeatureThe Real Story Behind the Lower Forty Shooting, Angling and Inside Straight Club

September 1990 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

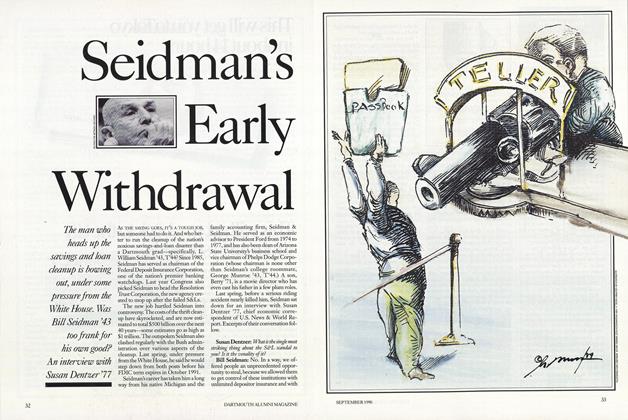

FeatureSeidman's Early Withdrawal

September 1990 By Susan Dentzer '77 -

Feature

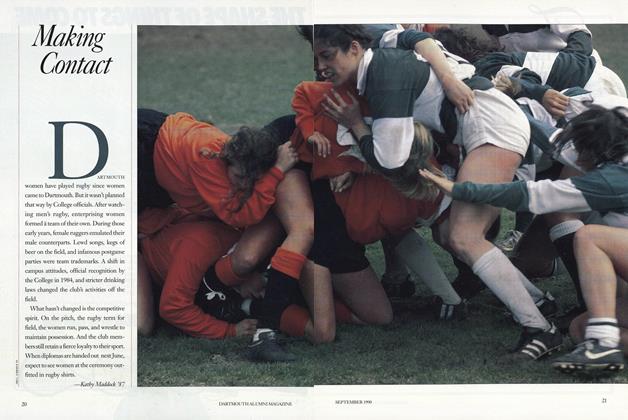

FeatureMaking Contact

September 1990 By Kathy Maddock '87 -

Article

ArticleMOTHERS AND DAUGHTERS

September 1990 By Professor Marianne Hirsch -

Article

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

September 1990 -

Class Notes

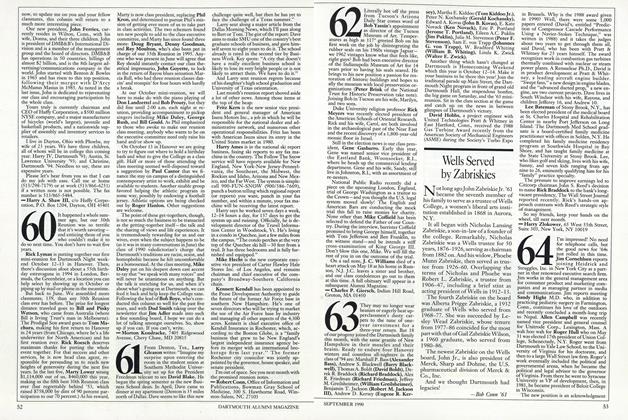

Class Notes1960

September 1990 By Morton Kondracke

Features

-

Feature

FeatureMammalogist

FEBRUARY 1967 -

Feature

FeatureJeffrey Hart Professor of English 20 million readers in a single column

January 1975 -

Feature

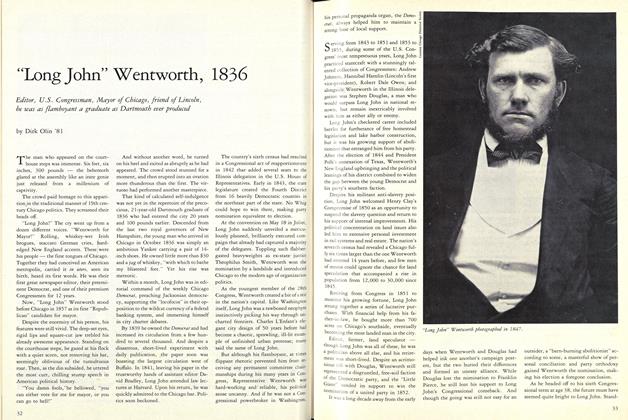

Feature"Long John" Wentworth, 1836

MARCH 1983 By Dirk Olin '81 -

Feature

FeaturePapa's Son

OCTOBER • 1986 By Everett Wood '38 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

Nov/Dec 2007 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

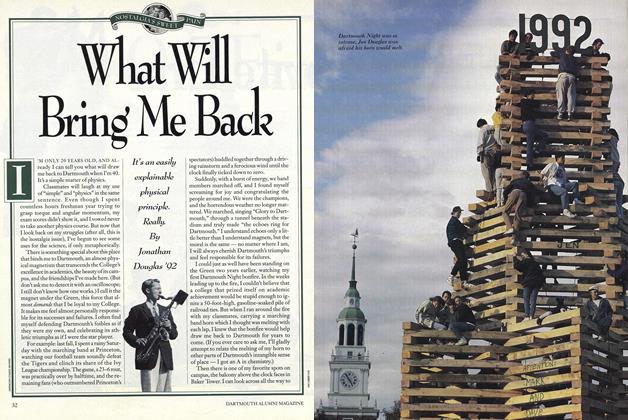

FeatureWhat Will Bring Me Back

MARCH 1991 By Jonathan Douglas '92, Richard Hovey