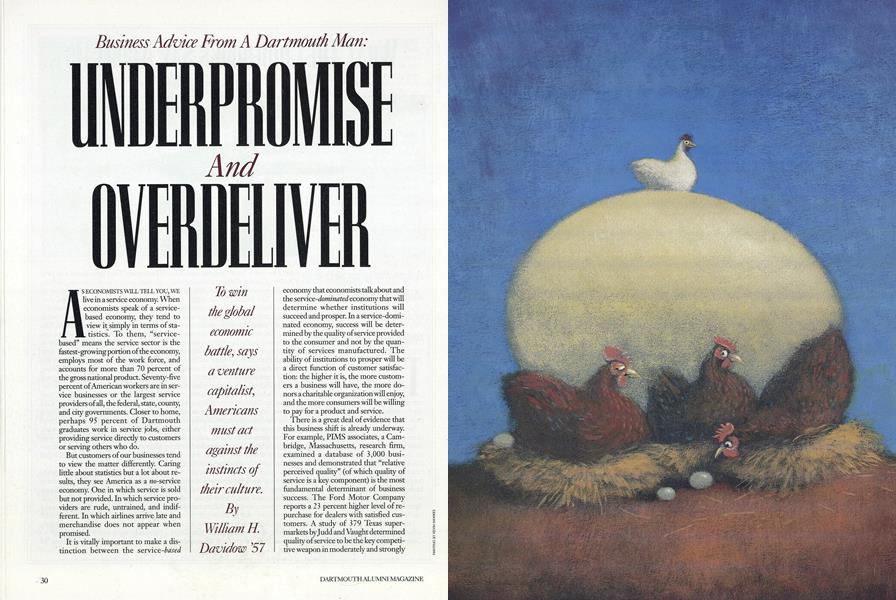

Business Advice From A Dartmouth Man:

AS ECONOMISTS WILL TELL YOU, WE live in a service economy. When economists speak of a servicebased economy, they tend to view it simply in terms of statistics. To them, "servicebased" means the service sector is the fastest-growing portion of the economy, employs most of the work force, and accounts for more than 70 percent of the gross national product. Seventy-five percent of American workers are in service businesses or the largest service providers of all, the federal, state, county, and city governments. Closer to home, perhaps 95 percent of Dartmouth graduates work in service jobs, either providing service directly to customers or serving others who do.

But customers of our businesses tend to view the matter differently. Caring little about statistics but a lot about results, they see America as a no-service economy. One in which service is sold but not provided. In which service providers are rude, untrained, and indifferent. In which airlines arrive late and merchandise does not appear when promised.

It is vitally important to make a distinction between the service-based economy that economists talk about and the service-dominated economy that will determine whether institutions will succeed and prosper. In a service-dominated economy, success will be determined by the quality of service provided to the consumer and not by the quantity of services manufactured. The ability of institutions to prosper will be a direct function of customer satisfaction: the higher it is, the more customers a business will have, the more donors a charitable organization will enjoy, and the more consumers will be willing to pay for a product and service.

There is a great deal of evidence that this business shift is already underway. For example, PIMS associates, a Cambridge, Massachusetts, research firm, examined a database of 3,000 businesses and demonstrated that "relative perceived quality" (of which quality of service is a key component) is the most fundamental determinant of business success. The Ford Motor Company reports a 23 percent higher level of repurchase for dealers with satisfied customers. A study of 379 Texas supermarkets by Judd and Vaught determined quality of service to be the key competitive weapon in moderately and strongly competitive markets. A study of banks by Raddon Financial Group concluded that 42 percent of consumers who switch banks do so because of service problems.

These studies as well as my personal observation of the business problems encountered by such service laggards as General Motors and Pan American, and the successes of service leaders such as L.L. Bean and Motorola show that service counts.

Unfortunately, success in providing service requires dedication to a set of values which are often foreign both to our culture and our education. The Latin base of the word service is servus, meaning slave. Not many of us in business like to think of ourselves as slaves to our customers and employees. We tend to view employees as working for managers and demanding customers as problems. Interestingly, most great service providers, such as Nordstrom, the upscale retailer that is taking the country by storm, espouse the view that customers and front-line employees who serve them are more important than the managers themselves. They typically draw inverted organization charts with the customer on top and the managers at the bottom with the frontline employees in the middle. The implication is that the people at the bottom are there to serve those at the top.

The message is clear: success in a service role requires a different way of thinking from the one to which most of us are accustomed.

I was involved in a study recently to determine what was different about the way great service providers think. The results were quite revealing.

Perhaps the most startling finding was that good service has very little to do with what is provided, but everything to do with what is expected. Set the consumers' expectations at the right level and then exceed those expectations, and you have provided good service. That's why we can feel we get good service at a McDonald's and not at a three-star restaurant in Paris we got what we expected at McDonald's and were treated like barbarians in Paris. But the process of setting expectations at the right level requires that we do something that is pretty foreign to our culture, namely that we underpromise and overdeliver.

Not many of us in financial services, advertising, capital equipment, or airline businesses follow that strategy. For example, United Airlines recently ran an advertising campaign announcing its "rededication to service" while racking up one of the industry's worst on-time arrival records. I am sure that few advertising account executives would have leveled with United's management and told them, "We will only make your perceived level of service worse by advertising your service as better."

In a service-dominated society, customers become a business's most important asset. For most companies, this will mean a complete overhaul in their strategic focus, employee motivation, and recognition systems. Today, most of us in business are compensated based on such objective measurements as quarterly profits, return on assets, and billable hours. Almost no one I know gets paid based on customer satisfaction.

We know in business that you get what you measure and reward. America's preoccupation with short-term quantifiable results has focused our institutions on narrow-mindedly producing those results. Our businesses are populated with leaders who put profit, perquisites, and income before customer satisfaction. Ask yourself: how many employees could hold a job in most businesses if they consistently did what was right for the customer at the expense of what was right for the profitand-loss statement? Well, more and more of us are going to have to do just that—put the customer first if we are going to succeed in the future.

Now, I know this all may sound like a lot of idealism from a customer-service fanatic, so I'd like to end with a very pragmatic observation.

I have spent most of the 30 years since I graduated from Dartmouth working in the high-technology field. From the West Coast we watched smugly as the Rust Bowl rusted, safe in our belief that we on the leading edge had nothing to fear as long as we stayed ahead technologically. We would simply out-invent the Japanese, we told ourselves. But the Japanese did catch up, using mature technology and two weapons lower costs and total quality control both of which created very satisfied customers. The key is that they based their attack on costs and customer satisfaction!

In his recent book Yen, Daniel Burstein argues that the Japanese will soon dominate world financial markets. One of the principle reasons is the massive amount of low-cost capital they have available. (Costs!) A poignant quote appears in Michael Lewis's book Liar's Poker, in which a customer complains, "We are tired of being ripped off by Drexel Burnham and Goldman Sachs and Salomon Brothers and the other Americans." (Customer satisfaction!)

I can see no reason why the same techniques the Japanese used to enfeeble the steel, automotive, semi-conductor, and consumer-electronics businesses in the USA will not work just as effectively in the banking, hospitality, real estate, and retailing businesses. They already are showing signs of doing so.

When I first became interested in service, I viewed it strictly as a pragmatic business issue, a way of helping the companies with which I was associated gain a significant competitive advantage. Today, I envision service as an issue of business values, because at the heart of providing great service is the requirement that the interests of others are paramount to our own. This demands a leap of faith, a belief that the resulting good will ultimately be paid back with either cash or emotional satisfaction. But the service-dominated economy of the future will require just that: an irrational act in order to win.

When McNuggets are on the menu, saysWilliam Davidow, we don't expect pate.

William H. Davidow '57 is the co-author, with Bro Uttal, of the book Total Customer Service, the Ultimate Weapon (Harper & Row). He is a general partner in the venture-capital firm-Mohr, Davidow Ventures in Menlo Park, California.

To win the global economic battle, says a venture capitalist, Americans must act against the instincts of their culture.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryDARTMOUTH IN THE MEDIA

October 1990 By Peter S. Prichard '66 -

Feature

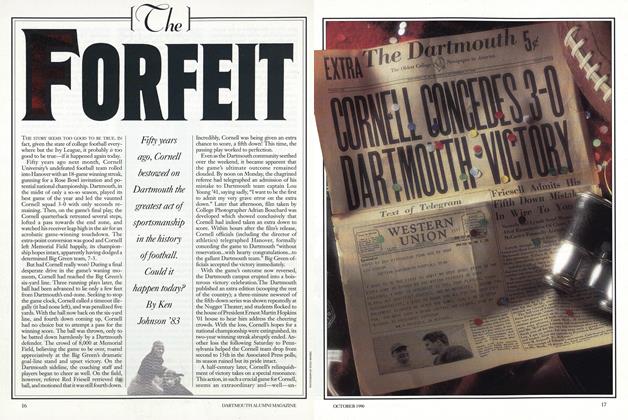

FeatureTHE FORFEIT

October 1990 By Ken Johnson '83 -

Article

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

October 1990 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1980

October 1990 By Michael H. Carothers -

Article

ArticleProf's Choice

October 1990 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1960

October 1990 By Morton Kondracke

Features

-

Feature

FeatureConclave in Cleveland

March 1961 -

Feature

Feature2. Drinking

December 1987 -

Feature

FeatureHarvard Myths About Dartmouth

September 1976 By ERICH SEGAL -

Feature

FeatureA MEMORANDUM

October 1975 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHoney, They're HOME

January 1996 By Mary Cleary Kiely '79 -

Feature

Feature"Hoppy"

January 1958 By ROBERT L. ALLEN '45